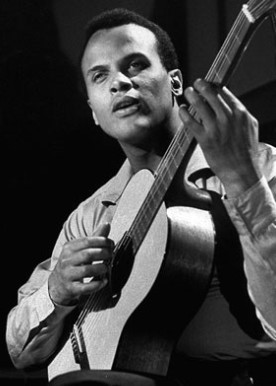

Books and Arts; Book Review;Harry Belafonte's autobiography;

Twentieth-century lion;

My Song: A Memoir of Art, Race and Defiance. By Harry Belafonte;

IT ALL began with a set of Venetian blinds. In 1946 a couple in a Manhattan apartment building asked their janitor, a biracial Jamaican New Yorker newly returned from naval service in the second world war, to install a set in their flat. The task completed, they gave him two theatre tickets as payment. The janitor, having no money for the dinner that a proper date would have included, went on his own to see “Home is the Hunter”, a play about black servicemen returning to America after the war. He was enraptured.

这一切要从一套百叶窗帘说起。故事发生在1946年的曼哈顿,有对夫妇想在家里安装一套百叶窗帘,于是便叫来一位公寓清洁工,作为报酬,事后给了他两张戏票。想来,邀人看戏起码得请吃个饭,可无奈囊中羞涩,这清洁工就自个儿去美国黑人剧院看了场《家是猎人》。这出戏讲述了一位美国黑人士兵战后返乡的事,看着看着这哥们就陶醉了。

The tenants, Clarice Taylor and Maxwell Glanville, performed in the play, which was put on by the American Negro Theatre (ANT). The janitor was, of course, Harry Belafonte.

剧中表演者正是那对夫妇,克莱斯·泰勒与麦斯威尔·格兰维尔;而那清洁工呢,自然就是哈利·贝拉方特;说来,那时二战刚刚终了,结束海军服役后,这个有着牙买加血统的美籍混血回到纽约,在一幢公寓里做起了清洁工。

In short order Mr Belafonte also found his way into the ANT, where he not only acted but made “my first friend in life”, another poor, hustling West Indian named Sidney Poitier. The two of them hatched get-rich-quick schemes—Mr Poitier wanted to market an extract of Caribbean conch as an aphrodisiac—and they shared theatre tickets: they could only afford a single ticket between them, so one would attend before the interval and one after, then each would fill the other in. Mr Poitier got his break first: he took Mr Belafonte's place in a play that the latter, still employed as a janitor, missed because he had to collect his tenants' rubbish. It took Mr Belafonte several more years of struggling, and he gained fame not as an actor, for which he had trained, but as a singer, for which he had not, filling time during the interval at Lester Young's concerts, where his first backup band included Max Roach and Charlie Parker.

不久后,贝拉方特也找到了通往美国黑人剧院的门路。在那儿,他不仅演戏,还结实了“生命中第一个朋友” 西德尼·波蒂埃。和贝拉方特一样,这个来自西印度群岛的小伙儿生活拮据,为了生计四处奔波。私下里,二人策划了快速致富的计划:加勒比贝壳的提取物可拿来当春药使,波蒂埃就想带着货去市场卖;此外,哥俩还共用一张戏票。由于只付得起一张票钱,两人就以幕间休息为准,你来半场,我来半场,互换位置。波蒂埃首先打开局面,并在一出戏中挤掉了贝拉方特的戏份。而贝拉方特仍旧干着清洁,因为他还得打扫房客的垃圾,遗憾得错过了机会。又是几年过去了,经过奋斗,贝拉方特终于获得成功。这一次,他没有拾起老本去演戏,而选择从未训练过的职业,做起了歌手:李斯特杨的音乐会上,幕间休息时常见他一展歌喉,那时,在他最初伴奏乐队里还有着像麦克斯·罗奇,查理·帕克这样的人物。

Looming over both this book and its subject's life are two ghosts: Millie, his formidable, perpetually dissatisfied mother; and Paul Robeson, whose combination of entertainment and political activism⑾ forged a path that Mr Belafonte would follow. But whereas Robeson's activism ran headlong into early cold-war paranoia, blacklists and McCarthyism, Mr Belafonte was luckier: his career rose more or less in tandem with the American civil-rights movement.

不论是本书还是贝拉方特的一生中,总有两朵阴霾不肯散去:一个是他的母亲米勒。这女人让人敬畏,而且永不知满足。另一个则是保罗·罗贝孙,他将娱乐与政治激进主义糅合,铺下前路,好让贝拉方特遵循。然而,正是他的激进行为,让其猛然栽入早期冷战妄想与麦卡锡主义中,并在各种黑名单上记录在案,与之相比,贝拉方特幸运多了:其职业生涯的崛起,多多少少与美国民权运动相连。

Martin Luther King junior sought him out in 1956, just a few months after rising to fame during the Montgomery bus boycott⒀. King was then 26, and a preacher at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, while Mr Belafonte was 28 and newly crowned “America's Negro matinée idol”. Mr Belafonte was sceptical of both religion and non-violence (“I wasn't nonviolent by nature,” he explains, “or if I was, growing up on Harlem's streets had knocked it out of me”), but was won over by King's humility. There is an especially touching scene from nine years later in which, following a celebrity-studded civil-rights fund-raiser in Paris, King, then a Nobel peace-prize winner, serves food to the assembled stars as “an exercise in humility, an act of abject gratitude to all these stars for coming out for him.” In a book that is riddled with many of the usual faults of celebrity autobiography—name-dropping, score-settling, preening and a rather ungallant treatment of his first wife and some of his children—Mr Belafonte's portrayal of King stands out for its unfussy warmth and unhagiographical affection.

1956年,蒙哥马利市爆发巴士抵制运动,一名来自德克斯特大街浸信会教堂的牧师声名鹊起。他,就是马丁·路德·金。几个月后,时年26岁的金找到贝拉方特,那时,后者28岁,新得美誉“通吃美国妇女的小黑哥”。贝拉方特不信教,也不信非暴力,(用他自己说是“我生来刚烈,就算不使用暴力,在哈林区混大,也叫人砸有了。”)却因金的谦逊而折服。九年后的一幕最是感人心脾:那是在巴黎举行的一场民权筹款会,到场的尽是知名人士,金,这位诺贝尔和平奖桂冠竟为在场的群星盛放实物, 以此向为他而来的群星们行以“谦恭之举”,表达心中“无尽感激”。贝拉方特的这本书中,明星自传常有的缺点满眼皆是:不是提一笔名人来拔高自己身价,就是报复之辞,要么自我吹捧几句,再不就是描写原配与孩子时,不甚殷切。所以,在对金的刻画,更凸显出他那份知性的温情与平实的情怀。

After the 1960s, “My Song” goes downhill quickly, but that is hardly a surprise: maintaining fame is never as interesting as achieving it. The book is also too long. Mr Belafonte's ramblings about business deals that went sour and his agonising over the extraordinary privileges his children enjoyed grow tedious. And then there is his political judgment. Standing with Martin Luther King junior to fight injustice and oppression is quite different from standing with practised political oppressors such as Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro. Still, Mr Belafonte does have a remarkable song to sing. Given its breadth, and the welcome disappearance of the segregated world in which it began, such a song will not be sung again.

上世纪60年代后,贝拉方特“唱”不动了,事业迅速下滑。但这并不奇怪:追逐名誉时,人们总是乐此不疲,但要永葆不衰,可就难咯。这本同名自传也够冗长的: 不是漫谈生意不顺,就讲孩子享受优待,当爹的很是焦虑的事,读着读着也觉得无聊。书中还叙述了其个人的政治判断:他既和老练得政治压迫者(比如雨果·查韦斯,菲德尔·卡斯特罗)有过交情,也曾与马丁·路德·金并肩,同歧视,压迫做过斗争。两者意义却大不相同。不过,贝拉方特还真有一首别致的歌要唱,但一来这歌受众不广,二来它出炉于种族隔离的时代,如今,人们早已敞开胸怀,愈合这个世界,如此看来⒆,此曲恐为绝唱哩!