Books and Arts; Book Review;

It all began with a set of Venetian blinds. In 1946 a couple in a Manhattan apartment building asked their janitor, a biracial Jamaican New Yorker newly returned from naval service in the second world war, to install a set in their flat. The task completed, they gave him two theatre tickets as payment. The janitor, having no money for the dinner that a proper date would have included, went on his own to see “Home is the Hunter”, a play about black servicemen returning to America after the war. He was enraptured.

故事还要从一扇百叶窗说起。1946年有一对夫妻住在曼哈顿一栋公寓楼里,公寓看门人,一个有着牙买加血统的纽约小伙子,刚从二战的海军服役中归来。一天这对夫妇请他帮忙安装一扇百叶窗,当小伙子任务完成后,他们给了他两张戏院的门票作为酬谢。考虑到付不起一次体面的约会必要的晚餐钱,看门人独自去看了《家是猎人》(Home is the hunter)。这部戏讲了一名黑人军人战后回美国的故事,小伙子看得入了迷。

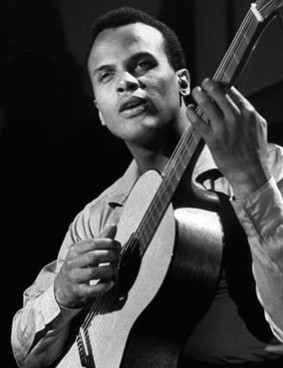

The tenants, Clarice Taylor and Maxwell Glanville, performed in the play, which was put on by the American Negro Theatre (ANT). The janitor was, of course, Harry Belafonte.

这部戏在美国黑人剧院(the American Negro Theatre ,ANT)上演,这对房客夫妻,Clarice Taylor 和 Maxwell Glanville,也参与了演出。这个看门人,当然就是故事的主人公亨瑞.贝拉方特(Harry Belafonte)。

In short order Mr Belafonte also found his way into the ANT, where he not only acted but made “my first friend in life”, another poor, hustling West Indian named Sidney Poitier. The two of them hatched get-rich-quick schemes—Mr Poitier wanted to market an extract of Caribbean conch as an aphrodisiac—and they shared theatre tickets: they could only afford a single ticket between them, so one would attend before the interval and one after, then each would fill the other in. Mr Poitier got his break first: he took Mr Belafonte's place in a play that the latter, still employed as a janitor, missed because he had to collect his tenants' rubbish. It took Mr Belafonte several more years of struggling, and he gained fame not as an actor, for which he had trained, but as a singer, for which he had not, filling time during the interval at Lester Young's concerts, where his first backup band included Max Roach and Charlie Parker.

Belafonte先生迅速地找到了进入ANT的方法,在那里他不仅练习表演,还交到了人生中第一个朋友Sidney Poitier,也是一个贫穷的拼命赚钱的小伙子,来自西印度群岛。两人一起策划出“快速来钱的计划”——Poitier先生想贩卖一种加勒比贝壳的汁液做成的催情剂——还一起分享戏院门票:两人只负担的起一张门票钱,所以往往一人观看上半场,另一人观看下半场,然后互相帮对方把整部戏串起来。Poitier先一步时来运转了:他在一部戏里替代Belafonte的角色,此时还在做看门人的Belafonte正在清理房客的垃圾,无奈错失良机。这使Belafonte花了更多年时间努力挣扎,终于赢得了名望,却不是作为一名专业的演员,而是一位业余的歌手。他在演出的幕间休息时去听Lester Young的演唱会打发时间,在那里遇到了他第一个后备乐队(the Charlie Parker band,译者注)的成员Max Roach 和 Charlie Parker。

Looming over both this book and its subject's life are two ghosts: Millie, his formidable, perpetually dissatisfied mother; and Paul Robeson, whose combination of entertainment and political activism forged a path that Mr Belafonte would follow. But whereas Robeson's activism ran headlong into early cold-war paranoia, blacklists and McCarthyism, Mr Belafonte was luckier: his career rose more or less in tandem with the American civil-rights movement.

在书中及主人公的生活中投下阴霾的鬼影,是Millie,令他畏惧的永远不满足的母亲;以及Paul Robeson,以政治激进主义为乐,并为Belafonte打造了一条政治道路。然而,尽管Robeson的激进主义使他盲目崇尚早期冷战偏执、黑名单、以及麦卡锡主义,Belafonte则更幸运:他事业的成就或多或少与他参与美国人权运动有关。

Martin Luther King junior sought him out in 1956, just a few months after rising to fame during the Montgomery bus boycott. King was then 26, and a preacher at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, while Mr Belafonte was 28 and newly crowned “America's Negro matinée idol”. Mr Belafonte was sceptical of both religion and non-violence (“I wasn't nonviolent by nature,” he explains, “or if I was, growing up on Harlem's streets had knocked it out of me”), but was won over by King's humility. There is an especially touching scene from nine years later in which, following a celebrity-studded civil-rights fund-raiser in Paris, King, then a Nobel peace-prize winner, serves food to the assembled stars as “an exercise in humility, an act of abject gratitude to all these stars for coming out for him.” In a book that is riddled with many of the usual faults of celebrity autobiography—name-dropping, score-settling, preening and a rather ungallant treatment of his first wife and some of his children—Mr Belafonte's portrayal of King stands out for its unfussy warmth and unhagiographical affection.

1956年,在蒙哥马利市(Montgomery)公车抵制运动后的几个月,在运动中声名鹊起的马丁路德金(Martin Luther King junior) 找到Belafonte。当时,26岁的King是蒙哥马利市Dexter Avenue Baptist Church 的传教士,28岁的Belafonte则是新晋的“美国黑人白天音乐会偶像”。Belafonte对宗教和非暴力皆持怀疑态度(“我天生就不是非暴力”他解释说,“就算我本性如此,在Harlem大街(纽约黑人住宅区,译者注)的成长经历也会使我脱离这种本性。”),但他被King的谦逊打动了。最触动人心的一幕发生在九年后,在巴黎举办的一场名人云集的民权基金募集会后,已经获得诺贝尔奖的King在就餐时为那些名人服务,作为“谦虚的表现,以及向为他而来的明星们表达的一点感激”。在这一本漏洞百出的书里,充满着通常明星自传中常有的缺点——自抬身价,利益相争,自我夸耀,以及甚至是无理的态度对待他的第一任妻子和他的某几个孩子——而Belafonte对King的这段描写,因为其平和的温暖以及不歌功颂德的感情流露而显得尤为突出。

After the 1960s, “My Song” goes downhill quickly, but that is hardly a surprise: maintaining fame is never as interesting as achieving it. The book is also too long. Mr Belafonte's ramblings about business deals that went sour and his agonising over the extraordinary privileges his children enjoyed grow tedious. And then there is his political judgment. Standing with Martin Luther King junior to fight injustice and oppression is quite different from standing with practised political oppressors such as Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro. Still, Mr Belafonte does have a remarkable song to sing. Given its breadth, and the welcome disappearance of the segregated world in which it began, such a song will not be sung again.

20世纪60年代后,很快Belafonte的事业开始走下坡路。但这丝毫不令人感到意外:守城永远没有攻城有意思。Belafonte的这本自传也长的让人生厌:Belafonte漫谈他不太顺利生意,Belafonte烦恼他家小孩享受特权,这些描写冗长又乏味。接着是他的政治判断:支持Martin Luther King junior反对不公正和压迫,与支持老练的政治压迫者,例如Hugo Chávez 和 Fidel Castro,是不尽相同的。鉴于年代的局限性,以及当时种族隔离的世界顺应人心地消失,Belafonte的这首生命之歌,将不会再被奏响。