I'm in the Asia Gallery at the back of the British Museum. Behind me stand two statues of the judges of the Chinese underworld, recording the good and the bad deeds of those who had died.

大英博物馆北区的亚洲厅摆放宥两尊中国阴间的判官雕像,他们是负责记录人生前的蒋举与恶行的,

And these judges were exactly the people that the Tang elite wanted to impress.

因此是庙朝的权资想要讨好的对象。

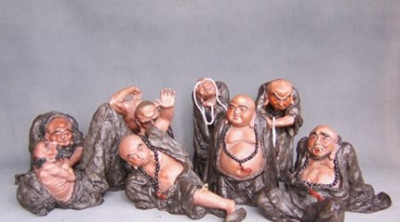

In front of me, I'm looking at a gloriously lively troupe of ceramic figures.

在他们前而摆放若一组十二只栩栩如牛的陶俑,

They're all between two and three feet (60 to 90 cm) high, and there are 12 of them-human, animal and somewhere in between.

高度在六十厢米至一百一十五厘米之间,形象包括人、舀以及人面兽身。

They're from the tomb of one of the great figures of Tang China, Liu Tingxun, general of the Zhongwu army, lieutenant of Henan and Huinan district and Imperial privy councillor, who died at the advanced age of 72 in 728.

它们都来自庙朝名将刘廷荀之墓。他曾任忠武将军、河南道与淮南道校尉以及中央枢密使, 在公元七二八年以七十二岁高龄去世。

Liu Tingxun tells us this, and a great deal more besides, in a glowing obituary that he had commissioned himself and which was buried along with his ceramic entourage.

这些倌息来自他命人撰写的墓志铭。这份铭文通篇溢美之词,与他的陶瓷随从们一同被下葬。

Together, figures and text give us a marvellous glimpse of China 1,300 years ago, but above all, they're a shamelessly barefaced bid for everlasting admiration and applause.

墓中的文字与物品让我们得以一窥一千三百年前的中国。但它们首先都是些寡廉鲜耻的自我吹捧,目的则是为了能名垂千古。

Wanting to control your own reputation after death isn't unknown today, as Anthony Howard, for years obituaries editor at The Times, recalls.

想要控制自己死后名声的人在如今也屡见不鲜。曾任《泰晤士报》讣闻版编辑的安东尼笛华德回忆。