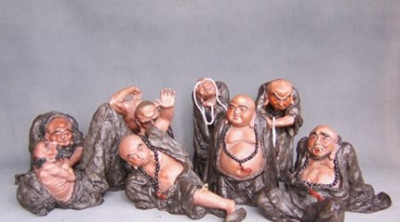

Ceramic figures like these were made in huge numbers for about 50 years, around 700. Their sole purpose was to be placed in high-status tombs. They have been found all around the great Tang cities of north-west China, where Liu Tingxun held office. The ancient Chinese believed you needed to have in the grave all the things which were essential to you in life. So the figures were just one element in the total contents of Liu Tingxun's tomb, which would also have contained sumptuous burial objects of silk and lacquer, silver and gold. While the animal and human statues would serve and entertain him, the supernatural guardian figures warded off malevolent spirits. You could hardly make better preparation for being dead!

公元700年左右,类似的陶俑在五十年间被大量制造,而其唯一用途便是立于位高权重者的坟墓之中。在刘廷荀任职的中国西北部,大型城市大量出土了这种陶俑。古代中国人认为,人应该用一切在世时的必需品作陪葬,因而陶俑只是刘廷苟墓葬的一部分,此外还有可观的丝绸、漆器、白银、黄金等奢侈物品。人俑与兽俑能够服侍和取悦墓主,神兽俑则用于驱邪镇魔。

Between their manufacture and their entombment, the ceramic figures would have been displayed to the living only once, when they were carried in the funeral cortege. They were never intended to be seen again. Once in the tomb, they took up their unchanging positions around the coffin, and then the stone door was firmly closed for eternity. A Tang poet of the time, Zhang Yue, commented:

从制造完工到人葬,这些陶俑应该只有一次在世人面前露面的机会,即在出殡时被运往墓地的过程中,此后便该永不再见天日。进入墓室之后,它们便按照一定位置围绕若棺木摆放,其后石门会被永久闭合。其时有位诗人张说评价道:

"All who come and go follow this road,

往来皆此路,

But living and dead do not return together."

生死不间归。

Like so much else in eighth-century China, the production of ceramic figures like these ones was controlled by an official bureau, just one small part of the enormous civil service that powered the Tang state.

与8世纪中国的各种物品一样,陶俑制造业受某个官方部门的控制,而该部门只是维系唐朝社会运行的庞大官吏系统中的一小部分。