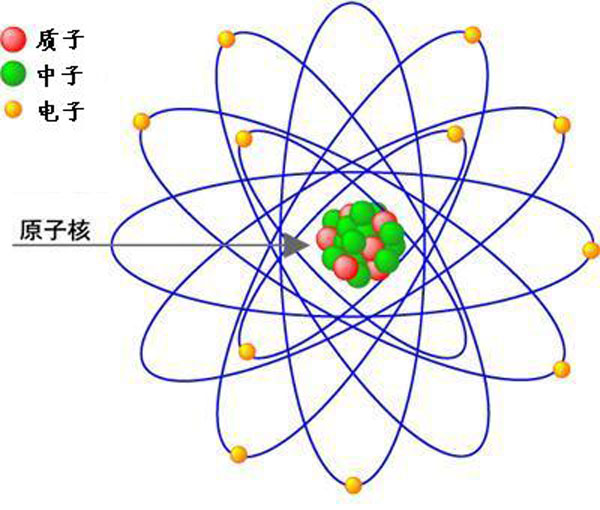

The picture that nearly everybody has in mind of an atom is of an electron or two flying around a nucleus, like planets orbiting a sun. This image was created in 1904, based on little more than clever guesswork, by a Japanese physicist named Hantaro Nagaoka. It is completely wrong, but durable just the same. As Isaac Asimov liked to note, it inspired generations of science fiction writers to create stories of worlds within worlds, in which atoms become tiny inhabited solar systems or our solar system turns out to be merely a mote in some much larger scheme. Even now CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, uses Nagaoka's image as a logo on its website. In fact, as physicists were soon to realize, electrons are not like orbiting planets at all, but more like the blades of a spinning fan, managing to fill every bit of space in their orbits simultaneously (but with the crucial difference that the blades of a fan only seem to be everywhere at once; electrons are ).

Needless to say, very little of this was understood in 1910 or for many years afterward. Rutherford's finding presented some large and immediate problems, not least that no electron should be able to orbit a nucleus without crashing. Conventional electrodynamic theory demanded that a flying electron should very quickly run out of energy—in only an instant or so—and spiral into the nucleus, with disastrous consequences for both. There was also the problem of how protons with their positive charges could bundle together inside the nucleus without blowing themselves and the rest of the atom apart. Clearly whatever was going on down there in the world of the very small was not governed by the laws that applied in the macro world where our expectations reside.