Jet streams, usually located about 30,000 to 35,000 feet up, can bowl along at up to 180 miles an hour and vastly influence weather systems over whole continents, yet their existence wasn't suspected until pilots began to fly into them during the Second World War. Even now a great deal of atmospheric phenomena is barely understood. A form of wave motion popularly known as clear-air turbulence occasionally enlivens airplane flights. About twenty such incidents a year are serious enough to need reporting. They are not associated with cloud structures or anything else that can be detected visually or by radar. They are just pockets of startling turbulence in the middle of tranquil skies. In a typical incident, a plane en route from Singapore to Sydney was flying over central Australia in calm conditions when it suddenly fell three hundred feet—enough to fling unsecured people against the ceiling. Twelve people were injured, one seriously. No one knows what causes such disruptive cells of air.

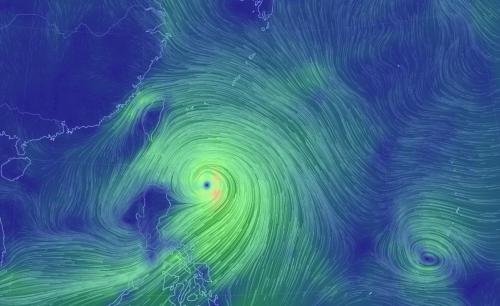

The process that moves air around in the atmosphere is the same process that drives the internal engine of the planet, namely convection. Moist, warm air from the equatorial regions rises until it hits the barrier of the tropopause and spreads out. As it travels away from the equator and cools, it sinks. When it hits bottom, some of the sinking air looks for an area of low pressure to fill and heads back for the equator, completing the circuit.