One of the oddities of our solar system is that the Sun burns about 25 percent more brightly now than when the solar system was young. This should have resulted in a much warmer Earth. Indeed, as the English geologist Aubrey Manning has put it, "This colossal change should have had an absolutely catastrophic effect on the Earth and yet it appears that our world has hardly been affected."

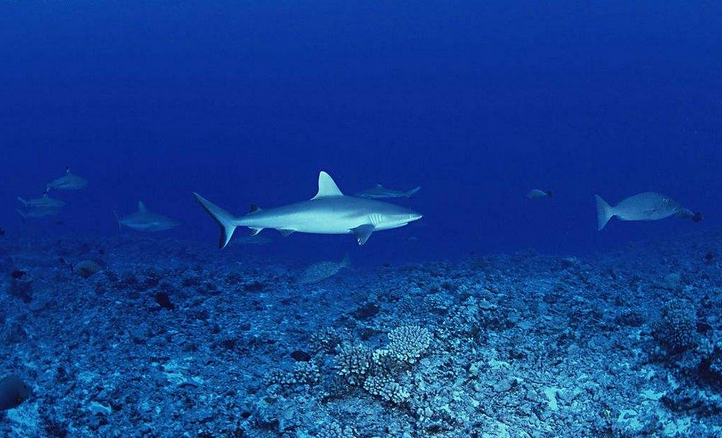

So what keeps the world stable and cool? Life does. Trillions upon trillions of tiny marine organisms that most of us have never heard of—foraminiferans and coccoliths and calcareous algae—capture atmospheric carbon, in the form of carbon dioxide, when it falls as rain and use it (in combination with other things) to make their tiny shells. By locking the carbon up in their shells, they keep it from being reevaporated into the atmosphere, where it would build up dangerously as a greenhouse gas. Eventually all the tiny foraminiferans and coccoliths and so on die and fall to the bottom of the sea, where they are compressed into limestone. It is remarkable, when you behold an extraordinary natural feature like the White Cliffs of Dover in England, to reflect that it is made up of nothing but tiny deceased marine organisms, but even more remarkable when you realize how much carbon they cumulatively sequester. A six-inch cube of Dover chalk will contain well over a thousand liters of compressed carbon dioxide that would otherwise be doing us no good at all.