For all the trouble they take to assemble and preserve themselves, species crumple and die remarkably routinely. And the more complex they get, the more quickly they appear to go extinct. Which is perhaps one reason why so much of life isn't terribly ambitious.

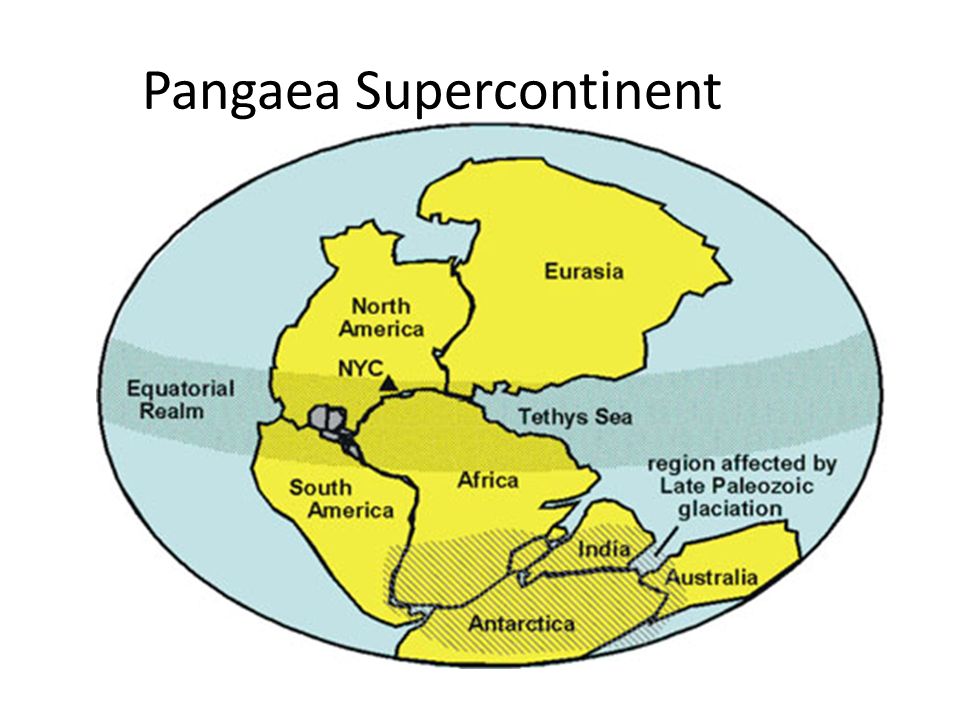

Land was a formidable environment: hot, dry, bathed in intense ultraviolet radiation, lacking the buoyancy that makes movement in water comparatively effortless. To live on land, creatures had to undergo wholesale revisions of their anatomies. Hold a fish at each end and it sags in the middle, its backbone too weak to support it. To survive out of water, marine creatures needed to come up with new load-bearing internal architecture—not the sort of adjustment that happens overnight. Above all and most obviously, any land creature would have to develop a way to take its oxygen directly from the air rather than filter it from water. These were not trivial challenges to overcome. On the other hand, there was a powerful incentive to leave the water: it was getting dangerous down there. The slow fusion of the continents into a single landmass, Pangaea, meant there was much, much less coastline than formerly and thus much less coastal habitat.