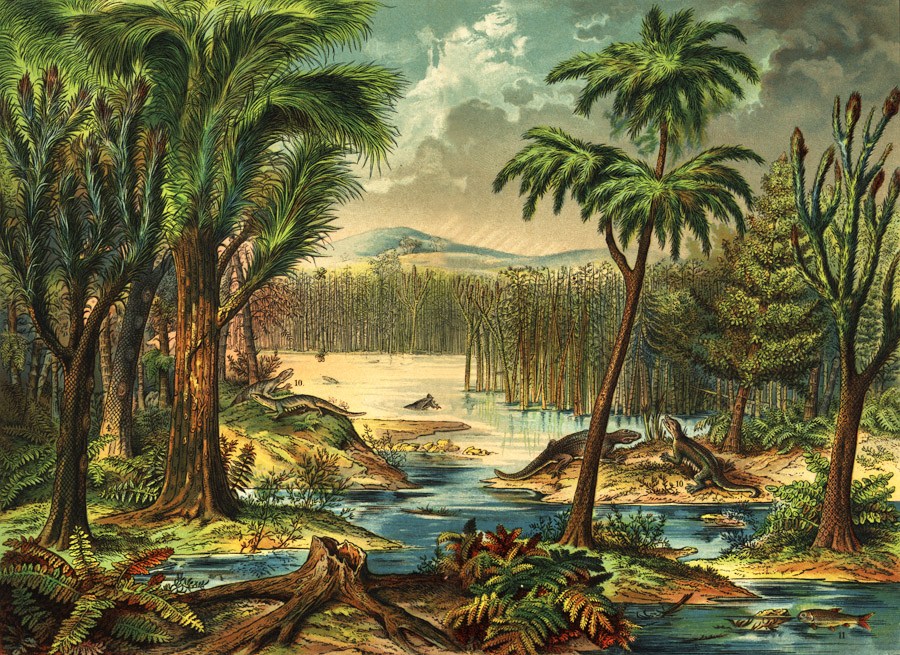

Then, as now, dragonflies could cruise at up to thirty-five miles an hour, instantly stop, hover, fly backwards, and lift far more proportionately than any human flying machine. "The U.S. Air Force," one commentator has written, "has put them in wind tunnels to see how they do it, and despaired." They, too, gorged on the rich air. In Carboniferous forests dragonflies grew as big as ravens. Trees and other vegetation likewise attained outsized proportions. Horsetails and tree ferns grew to heights of fifty feet, club mosses to a hundred and thirty.

The first terrestrial vertebrates—which is to say, the first land animals from which we would derive—are something of a mystery. This is partly because of a shortage of relevant fossils, but partly also because of an idiosyncratic Swede named Erik Jarvik whose odd interpretations and secretive manner held back progress on this question for almost half a century. Jarvik was part of a team of Scandinavian scholars who went to Greenland in the 1930s and 1940s looking for fossil fish. In particular they sought lobe-finned fish of the type that presumably were ancestral to us and all other walking creatures, known as tetrapods.