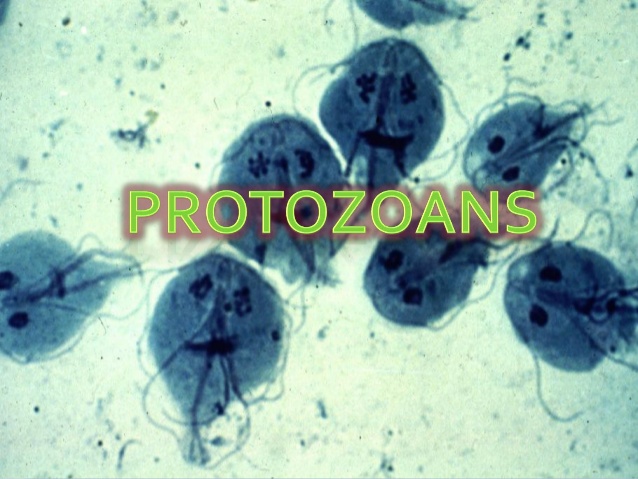

Go out into a woods — any woods at all — bend down and scoop up a handful of soil, and you will be holding up to 10 billion bacteria, most of them unknown to science. Your sample will also contain perhaps a million plump yeasts, some 200,000 hairy little fungi known as molds, perhaps 10,000 protozoans (of which the most familiar is the amoeba), and assorted rotifers, flatworms, roundworms, and other microscopic creatures known collectively as cryptozoa. A large portion of these will also be unknown.

The most comprehensive handbook of microorganisms, Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, lists about 4,000 types of bacteria. In the 1980s, a pair of Norwegian scientists, Jostein Goksoyr and Vigdis Torsvik, collected a gram of random soil from a beech forest near their lab in Bergen and carefully analyzed its bacterial content. They found that this single small sample contained between 4,000 and 5,000 separate bacterial species, more than in the whole of Bergey's Manual. They then traveled to a coastal location a few miles away, scooped up another gram of earth, and found that it contained 4,000 to 5,000 other species. As Edward O. Wilson observes: "If over 9,000 microbial types exist in two pinches of substrate from two localities in Norway, how many more await discovery in other, radically different habitats?" Well, according to one estimate, it could be as high as 400 million.