As laboratory specimens fruit flies had certain very attractive advantages: they cost almost nothing to house and feed, could be bred by the millions in milk bottles, went from egg to productive parenthood in ten days or less, and had just four chromosomes, which kept things conveniently simple.

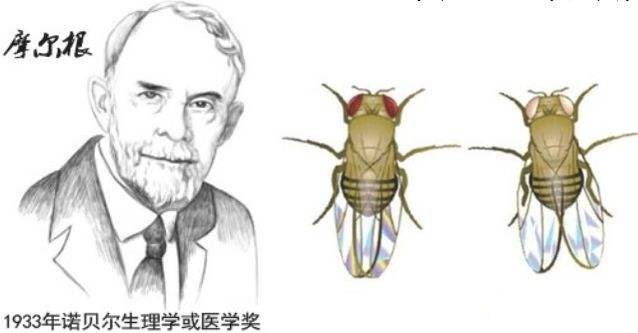

Working out of a small lab (which became known inevitably as the Fly Room) in Schermerhorn Hall at Columbia University in New York, Morgan and his team embarked on a program of meticulous breeding and crossbreeding involving millions of flies (one biographer says billions, though that is probably an exaggeration), each of which had to be captured with tweezers and examined under a jeweler's glass for any tiny variations in inheritance. For six years they tried to produce mutations by any means they could think of — zapping the flies with radiation and X-rays, rearing them in bright light and darkness, baking them gently in ovens, spinning them crazily in centrifuges — but nothing worked. Morgan was on the brink of giving up when there occurred a sudden and repeatable mutation — a fly that had white eyes rather than the usual red ones. With this breakthrough, Morgan and his assistants were able to generate useful deformities, allowing them to track a trait through successive generations. By such means they could work out the correlations between particular characteristics and individual chromosomes, eventually proving to more or less everyone's satisfaction that chromosomes were at the heart of inheritance.