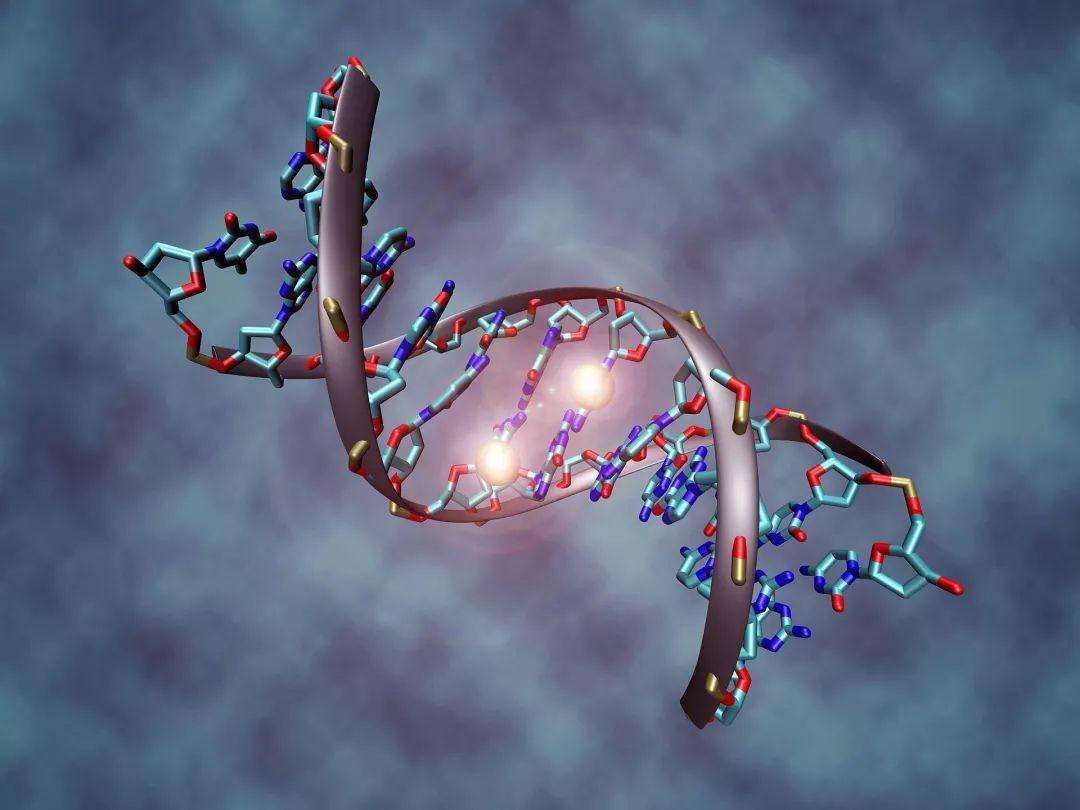

Most of the time our DNA replicates with dutiful accuracy, but just occasionally — about one time in a million — a letter gets into the wrong place. This is known as a single nucleotide polymorphism, or SNP, familiarly known to biochemists as a "Snip." Generally these Snips are buried in stretches of noncoding DNA and have no detectable consequence for the body. But occasionally they make a difference. They might leave you predisposed to some disease, but equally they might confer some slight advantage — more protective pigmentation, for instance, or increased production of red blood cells for someone living at altitude. Over time, these slight modifications accumulate in both individuals and in populations, contributing to the distinctiveness of both.

The balance between accuracy and errors in replication is a fine one. Too many errors and the organism can't function, but too few and it sacrifices adaptability. A similar balance must exist between stability in an organism and innovation. An increase in red blood cells can help a person or group living at high elevations to move and breathe more easily because more red cells can carry more oxygen. But additional red cells also thicken the blood. Add too many, and "it's like pumping oil," in the words of Temple University anthropologist Charles Weitz. That's hard on the heart. Thus those designed to live at high altitude get increased breathing efficiency, but pay for it with higher-risk hearts.