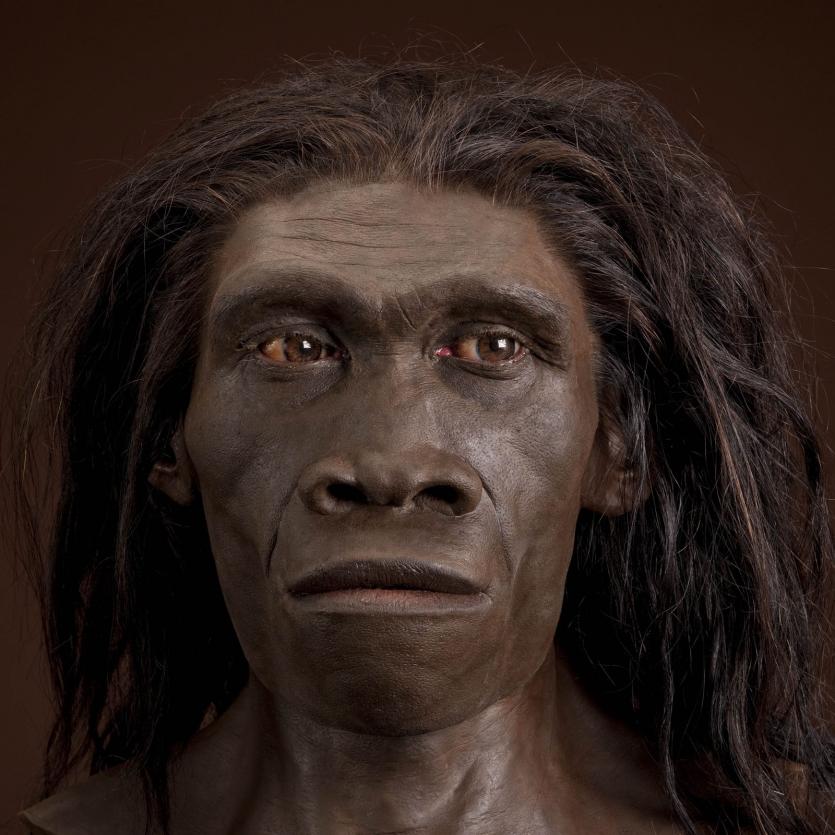

Although erectus had been known about for almost a century it was known only from scattered fragments—not enough to come even close to making one full skeleton. So it wasn't until an extraordinary discovery in Africa in the 1980s that its importance—or, at the very least, possible importance—as a precursor species for modern humans was fully appreciated. The remote valley of Lake Turkana (formerly Lake Rudolf) in Kenya is now one of the world's most productive sites for early human remains, but for a very long time no one had thought to look there. It was only because Richard Leakey was on a flight that was diverted over the valley that he realized it might be more promising than had been thought. A team was dispatched to investigate, but at first found nothing. Then late one afternoon Kamoya Kimeu, Leakey's most renowned fossil hunter, found a small piece of hominid brow on a hill well away from the lake. Such a site was unlikely to yield much, but they dug anyway out of respect for Kimeu's instincts and to their astonishment found a nearly complete Homo erectus skeleton. It was from a boy aged between about nine and twelve who had died 1.54 million years ago. The skeleton had "an entirely modern body structure," says Tattersall, in a way that was without precedent. The Turkana boy was "very emphatically one of us."

Also found at Lake Turkana by Kimeu was KNM-ER 1808, a female 1.7 million years old, which gave scientists their first clue that Homo erectus was more interesting and complex than previously thought. The woman's bones were deformed and covered in coarse growths, the result of an agonizing condition called hypervitaminosis A, which can come only from eating the liver of a carnivore. This told us first of all that Homo erectus was eating meat. Even more surprising was that the amount of growth showed that she had lived weeks or even months with the disease. Someone had looked after her. It was the first sign of tenderness in hominid evolution.