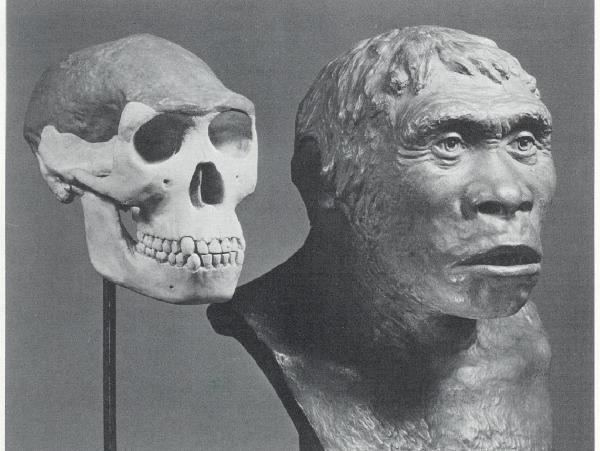

The traditional theory to explain human movements—and the one still accepted by the majority of people in the field—is that humans dispersed across Eurasia in two waves. The first wave consisted of Homo erectus, who left Africa remarkably quickly—almost as soon as they emerged as a species—beginning nearly two million years ago. Over time, as they settled in different regions, these early erects further evolved into distinctive types—into Java Man and Peking Man in Asia, and Homo heidelbergensis and finally Homo neanderthalensis in Europe.

Then, something over a hundred thousand years ago, a smarter, lither species of creature— the ancestors of every one of us alive today—arose on the African plains and began radiating outward in a second wave. Wherever they went, according to this theory, these new Homo sapiens displaced their duller, less adept predecessors. Quite how they did this has always been a matter of disputation. No signs of slaughter have ever been found, so most authorities believe the newer hominids simply outcompeted the older ones, though other factors may also have contributed. "Perhaps we gave them smallpox," suggests Tattersall. "There's no real way of telling. The one certainty is that we are here now and they aren't."