"Bottini!" exclaimed the master at length, fixing his eyes on the brick floor where the sunlight formed a checker-board. "Oh! I remember well! Your mother was such a good woman! For a while, during your first year, you sat on a bench to the left near the window. Let us see whether I do not recall it. I can still see your curly head." Then he thought for a while longer. "You were a lively lad, eh? Very. The second year you had an attack of croup. I remember when they brought you back to school, emaciated and wrapped up in a shawl. Forty years have elapsed since then, have they not? You are very kind to remember your poor teacher. And do you know, others of my old pupils have come hither in years gone by to seek me out: there was a colonel, and there were some priests, and several gentlemen." He asked my father what his profession was. Then he said, "I am glad, heartily glad. I thank you. It is quite a while now since I have seen any one. I very much fear that you will be the last, my dear sir."

“勃谛尼君!”先生注视着受着日光的地板说。“啊!我还很记得呢!你母亲是个很好的人。你在一年级的时候坐在窗口左侧的位置上。慢点!是了,是了!你那鬈曲的头发还如在眼前哩!”先生又追忆了一会儿;“你曾是个活泼的孩子,非常活泼。不是吗?在二年级那一年,曾患过喉痛病,回到学校来的时候非常消瘦,裹着围巾。到现在已四十年了,居然还不忘记我,真难得!旧学生来访我的很多,其中有做了大住的,做牧师的也有好几个,此外,还有许多已成了绅士。”先生问了父亲的职业,又说:“我真快活!谢谢你!近来已经不大有人来访问我了,你恐怕是最后的一个了!”

"Don't say that," exclaimed my father. "You are well and still vigorous. You must not say that."

“哪里!你还康健呢!请不要说这样的话!”父亲说。

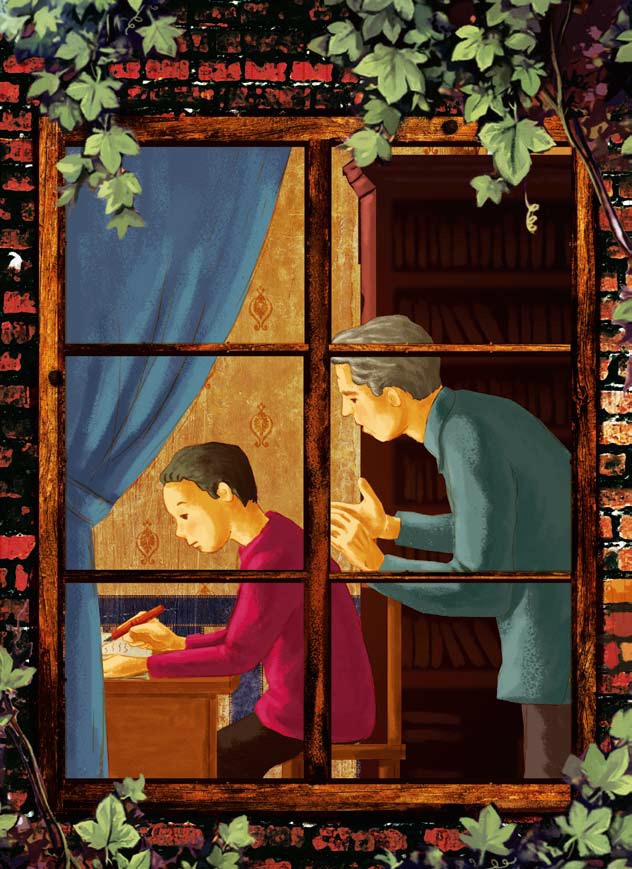

"Eh, no!" replied the master; "do you see this trembling?" and he showed us his hands. "This is a bad sign. It seized on me three years ago, while I was still teaching school. At first I paid no attention to it; I thought it would pass off. But instead of that, it stayed and kept on increasing. A day came when I could no longer write. Ah! that day on which I, for the first time, made a blot on the copy-book of one of my scholars was a stab in the heart for me, my dear sir. I did drag on for a while longer; but I was at the end of my strength. After sixty years of teaching I was forced to bid farewell to my school, to my scholars, to work. And it was hard, you understand, hard. The last time that I gave a lesson, all the scholars accompanied me home, and made much of me; but I was sad; I understood that my life was finished. I had lost my wife the year before, and my only son. I had only two peasant grandchildren left. Now I am living on a pension of a few hundred lire. I no longer do anything; it seems to me as though the days would never come to an end. My only occupation, you see, is to turn over my old schoolbooks, my scholastic journals, and a few volumes that have been given to me. There they are," he said, indicating his little library; "there are my reminiscences, my whole past; I have nothing else remaining to me in the world."

“不,不!你看!手这样颤动呢!这是很不好的。三年前患了这毛病,那时还在学校就职,最初也不注意,总以为就会痊愈的,不料竟渐渐重起来,终于宇都不能写了。啊!那一天,我从做教师以来第一次把墨水落在学生的笔记簿上的那一天,真是裂胸似的难过啊!虽然这样,总还暂时支持着。后来真的尽了力,在做教师的第六十年,和我的学校,我的学生,我的事业分别了,真难过啊!在最后授课的那天,学生一直送我到了家里,还恋恋不舍。我悲哀之极,以为我的生涯从此完了!不幸,妻适在前一年亡故,一个独子,不久也跟着死了,现在只有两个做农夫的孙子。我靠了些许的养老金,终目不做事情。日子长长地,好像竟是不会夜!我现在的工作,每日只是重读以前学校里的书,或是翻读日记,或是阅读别人送给我的书。在这里呢。”说着指书架,“这是我的记录,我的全生涯都在虫面。除此以外,我没有留在世界上的东西了!”