JEFFREY BROWN:And finally tonight, we end where we began, with Afghanistan, but this time through a very different lens, one of language and culture.

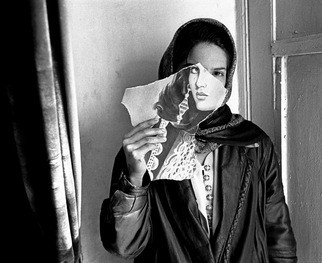

For many Americans, Afghanistan is a country shrouded in mystery, particularly its women, literally shrouded under a burka, silent and seemingly impenetrable.

ELIZA GRISWOLD, Journalist: As a Westerner, I would look for years at these blue burkas, thinking, those women beneath are chattel. They have nothing to say, because they're not—I don't hear them saying anything.

JEFFREY BROWN:Journalist Eliza Griswold has reported from Afghanistan for the last 10 years. She wanted to get beyond the headlines, and especially to understand the lives of rural women, mostly illiterate Pashtuns living along the border areas with Pakistan, amid the daily realities of war.

Her way in was through short poems called landays, each just two lines long, with 22 syllables.

WOMAN:"Separation, you set fire in the heart and home of every lover."

ELIZA GRISWOLD:This is rural folk poetry. This is poetry that's meant to be oral. It's passed mouth to mouth, ear to ear. And the women have recited these poems for centuries.

So they have gone from talking about the riverbank, which is the place you gather water and, of course, the place men go to spy on the women they have crushes on, to Facebook, to the Internet. And so they really reflect the currents that women in Afghanistan are encountering today.

JEFFREY BROWN:A poet herself, Griswold collaborated with photographer and filmmaker Seamus Murphy. Poetry magazine is devoting its entire June issue to their work.

And as part of the project, Murphy has made a short documentary featuring the landays.

WOMAN:"I could have tasted death for a taste of your tongue, watching you eat ice cream when we were young."

JEFFREY BROWN:As with poetry everywhere, one theme is love. But there's a whole lot more.

WOMAN:Slide your hand into my bra. Stroke a red and ripening pomegranate of Kandahar.

ELIZA GRISWOLD:Pull that burka back, and she will talk to you about the size of her husband's manhood. She will go right for it: sex, raunch, kissing, rage. She will talk about the rage of what it is to be cast in this role of subservient, in a way that's really startling.

JEFFREY BROWN:The rage Griswold speaks of is another theme, aimed at the unequal and often harsh treatment of women.

WOMAN:"When sisters sit together, they always praise their brothers. When brothers sit together, they sell their sisters to others."

JEFFREY BROWN:Griswold says landays are a way to subvert a social code in which many rural women are prohibited from speaking freely.

ELIZA GRISWOLD:They're a way to be very outspoken, but not to own the authorship of that statement, because, being collective and anonymous, a woman can say this and she can say, well, of course, I just heard that on the phone, or I just heard that in the market. I didn't make that up.

JEFFREY BROWN:That's in a society where they are otherwise not allowed to speak, not allowed to write poems.

ELIZA GRISWOLD:At all.

JEFFREY BROWN:With real danger, dangerous consequences.

ELIZA GRISWOLD:Exactly.

JEFFREY BROWN:In fact, this project began after Griswold wrote a magazine article on a young woman who'd been beaten for writing poems, and later killed herself.

Given stories like that, it was also tricky to collect the landays.

ELIZA GRISWOLD:Frequently, to meet these women, I had to be undercover to some extent. I had to wear a burka of their request. "Please come dressed as one of us. We will gather on Saturday afternoon. Our husbands will be out."

We started in refugee camps around Kabul, and we would hit situations like—first of all, Seamus and I were never able to work together, because it is impossible for him as a man to witness women singing or saying these landays.

JEFFREY BROWN:They just won't do it?

ELIZA GRISWOLD:They would be killed to be found out to do it.

JEFFREY BROWN:Another major theme of the landays is the pain and sorrow of war.

WOMAN:"In battle, there should be two brothers, one to be martyred, one to wind the shroud of the other."

ELIZA GRISWOLD:There's a lot of anger at the Taliban, a lot of rage at the hypocrisy of the Taliban, and an equal amount, if not more, rage at the hypocrisy of the Americans and what their influence has left behind.

Many of the women who were sharing them with us were survivors of very recent bombing attacks. One woman had shared a landay about her cousin, a Talib who'd just been killed by a drone strike.

WOMAN:"The drones have come to the Afghan sky. The mouths of our rockets will sound in reply."

JEFFREY BROWN:The mention of drones is also an example of how landays respond to changes in society. Verses that once mentioned the British now substitute Americans. And today, landays are shared on the Internet and in social media, and those new technologies make their way into the updated verses.

WOMAN:"How much simpler can love be? Let's get engaged now. Text me."

JEFFREY BROWN:What happens to this form in the future? What—is it your sense that it might die off because of changes in the country? Or does it have a life?

ELIZA GRISWOLD:So, I asked one of the leading novelists in Afghanistan, a guy named Mustafa Salek, what he thought. What will happen to the landay now they talk about the Internet, Facebook, drones? It will kill them. And he said just the opposite. They're being traded and they are changing, right, being remixed like rap is, at a rapid speed, and people love them.

The landay is supposed to communicate in the most natural language the truth of Afghan life. So, I found my assumptions about the death of the landay being absolutely confounded by what Afghans said themselves.

JEFFREY BROWN:Just another assumption confounded in this rare look behind the veil.

And, for the record, Poetry magazine, which is featuring the landays this month, is produced by the Poetry Foundation, which helps support our coverage.

And there's more on all of this online, where photographer Seamus Murphy narrates a slide show of his images for the project.