This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

Chocolate may appear to have little in common with crude oil. But production for consumers requires that both substances travel through pipes. And the thicker—that is, the more viscous—they are, the more likely they'll clog up those pipes. So physicists at Temple University in Philadelphia have devised an unusual solution to avoid that sticky situation: apply an electric field.

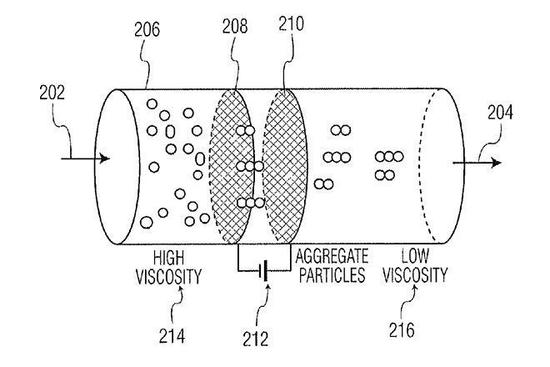

The process relies on a concept called electrorheology, in which a fluid can morph from a liquid to a JELL-O–like consistency, or the other way around, in an electric field. The field causes particles in the fluid, like paraffin and asphalt particles in crude oil, or cocoa and milk solids in chocolate, to act like tiny bar magnets, and line up into chains.

And the team's latest finding could be a boon for the production of low-fat chocolate. Because cutting the fat content of chocolate tends to jam up the pipes—what you might call the Augustus Gloop effect.

But that blockage can be cleared by applying an electric field of 1600 volts per centimeter, parallel to the chocolate's flow. The effect would allow chocolatiers to cut cocoa butter by 10 to 20 percent and still not clog the pipes. The study appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The authors claim the resulting chocolate has a stronger cocoa flavor, and tastes quote, "wonderful." And since the study was funded in part by the Mars Chocolate company—and other chocolate makers are interested—the researchers say the tech may be commercialized within a year. At which point you can judge for yourself whether electric fields really make a better bar. Or if the taste is simply shocking.

Thanks for listening Scientific American — 60-Second Science Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.