This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

The sun spews out ultraviolet radiation—that's why you put on sunscreen. But the sun isn't the only UV-producing celestial body. "Stars and supermassive black holes produce a huge amount of UV radiation." Michele Fumagalli, an astrophysicist at Durham University in the U.K. "And some of this radiation can escape a galaxy, and so this radiation builds up this cosmic UV background."

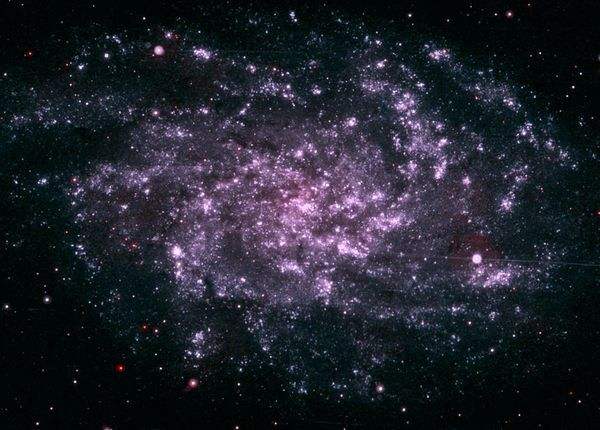

That cosmic UV background permeates the universe. But it's diffuse—meaning hard to measure, especially from here on Earth. "And so the way we do this measurement is with a little trick." That is, when UV radiation hits gas, it gives off a red glow. So Fumagalli and his team used what's called the MUSE instrument at the Very Large Telescope in Chile to stare—for hours—at the edge of a superthin galaxy, until they saw that red glow.

And since they knew how much gas was there, they were able to calculate the intensity of the UV radiation hitting the gas—the cosmic UV background. The finding is in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

That calculation offered clues to another celestial mystery, why we don't see as many small galaxies in the universe as theory would predict. Fumagalli says the UV background radiation might strip away valuable star-forming gas from the small guys.

"This is what happens to the small galaxies in the universe. They have gas, which is what's needed to form stars. But if that gas is radiated by intense UV radiation, essentially it evaporates. Which means the galaxies lose their supply of fuel to make new stars. Meaning they don't shine and we do not see them."

So the small galaxies remain dark. But bigger galaxies have a much smaller surface-to-volume ratio of star-forming gas—imagine a whole ocean of water compared to a tiny glassful. UV radiation can't strip away all the gas. So stars form. Like our sun. Which, when it comes to ultraviolet radiation here on Earth, is still the star of the show.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.