This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

The square footage of a home tends to be a measure of wealth. Compare the sizes of dwellings in a city and you'll get begin to get a picture of rich and poor, and how wealth is distributed.

Now researchers have used that modern metric on ancient settlements. They investigated housing-based wealth at 63 archaeological sites, from Old World places like Mesopotamia to New World sites like Mesa Verde in Colorado.

As expected, the wealth differential widened as agriculture took off. And it kept growing in the Old World. But in the Americas the gap suddenly stopped growing about 2500 years after the first crops showed up.

"Well, this was a surprise first of all." Timothy Kohler is an archaeologist at Washington State University. His team's hypothesis for the differences between hemispheres? The Old World had large domesticated animals—and that they say was a game changer.

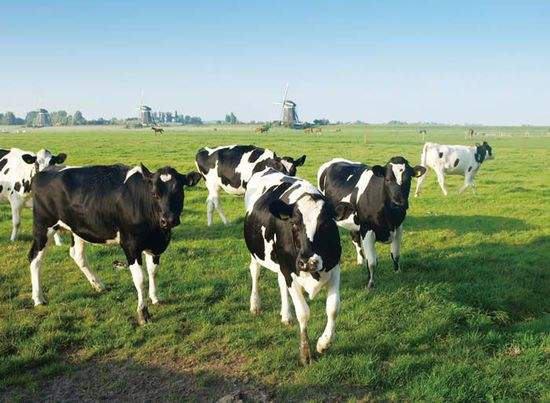

"Because if you have a team of oxen available, then you can farm much further from your house, and you can also farm much more land, and raise your income quite dramatically." That sort of farming is land-hungry, he says. So, over time, landowners with beasts of burden got richer at the expense of landless peasants.

The study is in the journal Nature.

Kohler says it's harder to scrutinize the holdings of the wealthy today, in an age of shell companies and offshore accounts. But he has this tip for future archaeologists:

"My advice to them would not be to look just at their main residence, but if they have residences in New York City or in the Bahamas or whatever, they need to add up all those residences and attribute them correctly to a single household."

Given the modern-day stats on the wealth gap, they'll probably uncover a society even more unequal than the ancient Old World.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.