This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Karen Hopkin.

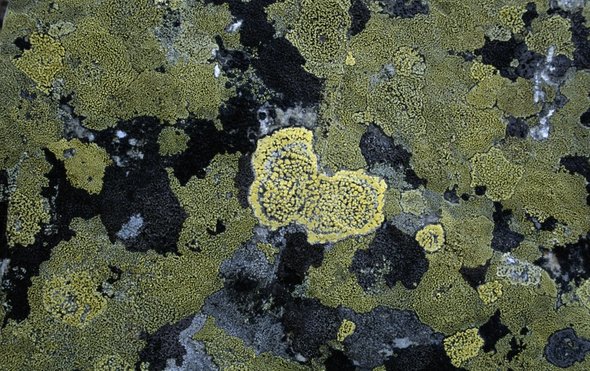

"Lichens are really cool successful organisms that are composed of at least two symbiotic partners: a fungal partner that provides structure and protection and a photosynthetic partner that likely provides energy in the form of sugar."

Cloe Pogoda, a graduate researcher at the University of Colorado. She led research that found that this partnership extends to the genetic level. The fungal partner in many lichen jettison a gene that's critical for energy production—making them completely dependent on their algal associates.

Although scientists have long appreciated that general division of labor, what's been less clear is whether the relationship was entirely obligatory. In other words, are the cohorts changed by their evolutionary association in such a way that they can no longer make it alone?

To find out, the team sequenced the genomes of 22 lichen species collected in the southern Appalachian Mountains. And they concentrated on the participants' mitochondria, which contain genomes of their own.

"Because there are so many copies of these genomes in each cell, and because they're so conserved across all domains of life, the mitochondrial genomes were the focus of our study." Kyle Keepers, also at the University of Colorado.

What the researchers found is that a key mitochondrial gene was missing from the fungal partner in 10 of the lichen species they examined. These species hailed from three different evolutionary lineages.

CP: "This is a really cool result because it demonstrates that this lichen relationship is obligate. And that the same strategy for genome streamlining was employed three different times over evolution." The findings appear in the journal Molecular Ecology.

Genome streamlining makes sense because it reduces redundancy on a molecular level.

"Think of it like two partners moving in together. And they each have their own printer. Who needs two printers?" Erin Tripp, the study's principal investigator, is the curator of botany at the university's Museum of Natural History.

Letting the algae provide the cellular energy likely makes the fungal partner more efficient, perhaps allowing it to focus on building a stable structure and reproducing. Tripp wonders whether some of the bacteria living in our guts might have developed similar molecular co-dependencies.

ET: "What this data analysis pipeline, moreover, creates is motivation to look for similar forms of gene loss in other types of symbioses, such as that between humans and their gut microbiomes. It may very well be that some bacteria are completely dependent on their human hosts and thus coevolving with us, whereas others can come and go."

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Karen Hopkin.