This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

Many bats use a system similar to sonar to navigate in the dark. They send out high frequency sound, sometimes as clicks, and get information about their surroundings by the timing and quality of the sound that bounces back. And just as turning up the light in a darkened room helps to illuminate the objects there, bats are known to turn up the intensity of their clicks when they have trouble detecting a target.

"Now, bats have had millions of years of evolution basically to sort of develop these mechanisms to dynamically adjust their emissions." Lore Thaler, a neuroscientist at Durham University in the U.K. "And what we were wondering is, well, do people do the same?"

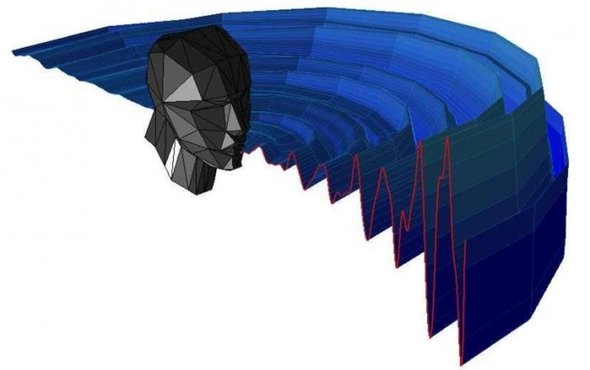

Because some people with impaired vision can indeed navigate using the echoes of finger snaps, hand claps, or mouth clicks (clicking sound). But it's not known how dynamic that ability is. So Thaler and her team presented eight expert echolocators with a challenge: could they tell whether a small dinner-plate-sized object was being held up about three feet from their head, by clicking alone?

You can try this at home by the way, with a plate or a book. "And if you hold it very close to your face while you're speaking you can notice that the sound that you hear really changes. This is because the sound that comes out of your mouth when you speak is reflected by the object you're holding in front of you. And that's an echo."

But move the plate 45 degrees to the side...then 90...then behind your head. And the task gets harder. But similar to the way bats do, the study subjects increased the number of clicks, and their loudness, (loud clicks) as the object became harder to detect—perhaps as a way to amplify the weak sounds echoing back.

The subjects still had trouble detecting the object a full 180 degrees behind them—they did only slightly better than chance. But they guessed correctly 80 percent of the time when the object was diagonally behind them. And nabbed nearly perfect scores when the disc was to the front or to the side. The results are in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Thaler says the study gives echolocating learners a shortcut: "If you're not sure, make a couple more clicks, and also make them louder." To produce echoes that more accurately reflect the world.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.