JUDY WOODRUFF: With some 10,000 baby boomers hitting retirement age every day, the problem of financial self-control, saving for the future, has become more and more pronounced. Our economics correspondent, Paul Solman, has been following the connection between saving and psychology for years.

The death last week of its seminal research, Walter Mischel, triggers this retrospective. It's part of our Making Sense series, which airs here every Thursday.

PAUL SOLMAN: How hard is it for you personally to save, instead of spending your money right away on something you want?

ACTOR: You know, we're not born knowing all these things.

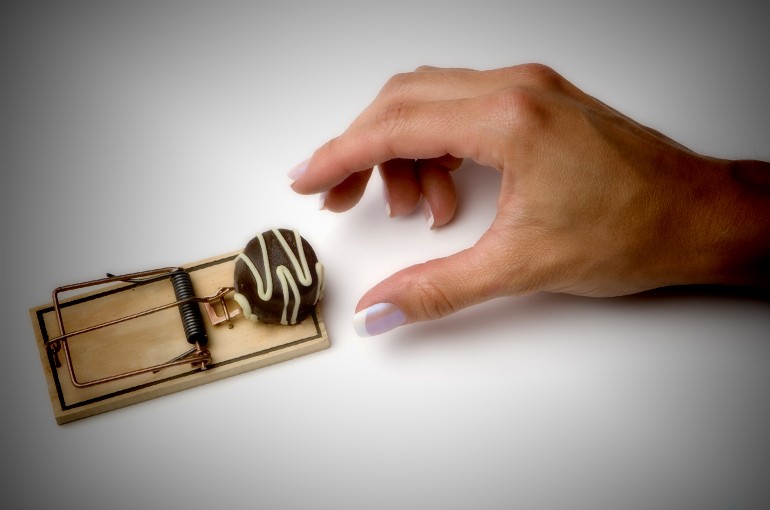

PAUL SOLMAN: An interview conducted on Sesame Street; itself a few years ago confirmed what many might have suspected, that Grover can no more delay gratification than many of his fellow Americans, who, on average, according to the Federal Reserve, have less than 4,000 dollars in savings, 57 percent of whom have less than 1,000 dollars to their names. But if you can maintain self-control, psychologist Walter Mischel told me:

WALTER MISCHEL, Psychologist: You have got a much more better chance of taking the future into account, and likely to have better economic outcomes.

PAUL SOLMAN: Mischel is known for an experiment he first ran at Stanford in 1960 with 4-to-6-year-olds and that you're probably familiar with: the marshmallow test, which I once ran on age-appropriate Grover. I will give you a marshmallow now, or if you wait a little while, I will give you two marshmallows.

ACTOR: Two marshmallows.

WALTER MISCHEL: Would it be hard to wait?

ACTOR: It would be very hard to wait, yes. Just looking at this marshmallow right now makes me what that marshmallow right now.

PAUL SOLMAN: Leaving aside the dubious charms of the foodstuff, the marshmallow test itself is actually among the most famous and replicated in the history of psychology.

WOMAN: There's a marshmallow. You can either wait, and I will bring you back another one, so you can have two, or you can eat it now.

CHILD: I want two.

WOMAN: OK, I will be back.

PAUL SOLMAN: Of the 600 preschoolers at Stanford on whom it was run, most wolfed down the little pillow of pleasure. But one-third delayed gratification long enough to get another.

WOMAN: You get two! Good job!

PAUL SOLMAN: Follow-up research found that the more temperate types had higher SAT scores as teens. And, later, an ongoing study of 1,000 random New Zealanders from birth to their 30s yielded even stronger findings. Their self-control, or lack of it, almost perfectly predicted their future prosperity. Duke Professor Terrie Moffitt:

TERRIE MOFFITT, Duke University: The children who are of very low self-control are in deep financial trouble by their 30s. Those who are very high self-control are doing really well. They're entrepreneurs. They have got retirement accounts. They own their own homes. And those who are average self-control are right in the middle.

PAUL SOLMAN: One challenge to the marshmallow results has suggested that trust in the experimenter is the key to resisting temptation. But Mischel was more interested in teaching kids how to resist, and found that the successful self-deniers employed very simple strategies.

WALTER MISCHEL: They transform an impossibly difficult situation into a relatively easy one by distracting themselves, by turning around.

PAUL SOLMAN: By putting the marshmallow farther away.

WALTER MISCHEL: Or I can do it by exploring my nasal cavities and my ear canals and toying with the product. The fancy word for it now is executive control. I'm able to use my prefrontal cortex, my cool brain, not my hot emotional system. I'm able to use my cool brain in order to have strategies that allow me to make this miserable, effortful waiting effortless and easy.

CHILD: Ten minutes! Ten minutes! Ten minutes!

PAUL SOLMAN: Or effortful and hard. A question that's played this research, is self-control hard-wired?

WALTER MISCHEL: I think some people find it much easier to exert control than others. But no matter whether one is reasonably good at this overall or reasonably bad at this overall, it can be enormously improved. But the idea that your child is doomed if she chooses not to wait for her marshmallows is really just a serious misinterpretation.

PAUL SOLMAN: And that's why Mischel worked for years with the KIPP charter school program to put his ideas into practice for those who he felt most needed them. The KIPP Infinity Middle School in New York City's Harlem, where, in addition to the three R's, these predominantly poor fifth-graders study character to maximize success in later life, qualities like grit and gratitude, optimism and curiosity, zest and social intelligence, and one skill above all.

WOMAN: What is this talking about, don't eat the marshmallow? Britney in the back.

STUDENT: Self-control?

WOMAN: OK, so we're talking about self-control.

PAUL SOLMAN: In fact, they have been talking about self-control since the first day of school, when teacher Leyla Bravo-Willey gave all of her students the marshmallow test. Walter Mischel's other major collaboration was with the Sesame Street Workshop on a series of videos starring their guru of gluttony to teach tiny tots how to delay gratification. So, a New Year's resolution. We had one more question for Mischel. And it formed the basis of a New Year's resolution story we did a few years ago: how to apply marshmallow test strategies as adults. So if I have a New Year's resolution to drink a little less than I do, what do I do?

WALTER MISCHEL: What you need is a plan that says, at the end of the day, 5:00 is the time that I am likely to have a drink.

PAUL SOLMAN: Right.

WALTER MISCHEL: OK? I have to have a substitute activity at that time, so there will be an alternative, and it'll be very, very practiced. I mean, to give you an example from my own experience, chocolate mousse is generally irresistible for me.

PAUL SOLMAN: His self-control strategy? WALTER MISCHEL: I will order the fruit salad. And that's a specific, rehearsed plan, so before the guy can tempt me with the mousse, I'm already ordering the fruit salad.

PAUL SOLMAN: Walter Mischel died last week at age 88, but, cliche though it is, his work lives on. This is economics correspondent Paul Solman reporting for the PBS NewsHour.