This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

The sun exerts an enormous and obvious influence on the Earth, with its gravity and light. But other bodies also have a small say in our affairs.

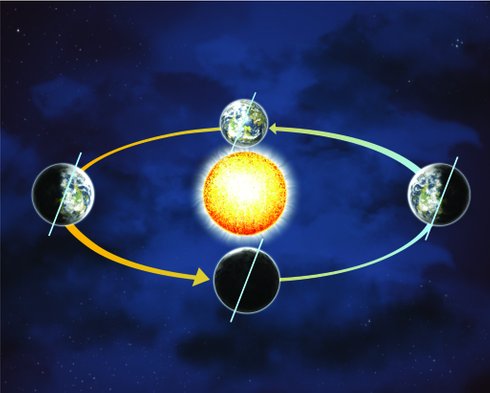

"We're not alone in the solar system, there are other planets." Dennis Kent, a geologist at Rutgers University, and Columbia's Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory. "And as we circle the sun, those other planets and also our moon exert effects on our orbit."

In fact, planetary scientists have long hypothesized that Venus and Jupiter squeeze the Earth's orbit from circular to elliptical and back every 405,000 years. During an elliptical orbit, when the distance from the sun varies more, the differences between the seasons would be more extreme than when the orbit is virtually circular. Problem is, it's been hard to verify that this oscillation between orbit shapes exists.

But Kent and his colleagues came up with a way—by boring down into the Earth. They took a rock core from the east coast, which has excellent sediment records—good evidence of extreme seasonal variations. They compared that core with another from Arizona, embedded with zircons. The zircons contain trace amounts of uranium, which decays in a predictable way—meaning the Arizona core could thus be dated based on uranium content.

Magnetic information in both cores allowed them to be lined up—and the Arizona dates then provided a timeline for the ancient floods and droughts embedded in the east coast core.

And all that evidence confirmed the mathematical simulations: Jupiter and Venus do push us around, and thus slowly alter our orbit over hundreds of millennia. The details are in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Kent says the discovery also provides a new way to interpret the history of life on the planet.

"It's a clock. And so being able to have a precise chronometer we can relate things like speciation events, or dispersals of various life forms. It allows us to look at these things and try to understand what's driving them."

As for whether modern-day humans need to worry about this 405,000-year oscillation?

"This is probably pretty low down the list of things to be concerned about. How much CO2 we're putting in the atmosphere, that's of a more immediate concern." Because, despite our planetary neighbors' best efforts, our orbit has barely budged as we've observed our climate change.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.