Welcome to the MAKING OF A NATION –American history in VOA Special English. In our last few programs, we describedthe presidential election campaign of eighteen-twenty-eight. It split the oldRepublican Party of Thomas Jefferson into two hostile groups: the NationalRepublicans of John Quincy Adams and the Democrats of Andrew Jackson. Theelection of Jackson deepened the split. It became more serious as a new disputearose over import taxes. This week in our series, Maurice Joyce and StewartSpencer continue the story of Andrew Jackson's presidency.

Congress passed a bill in eighteentwenty-eight that put high taxes on a number of imported products. The purposeof the import tax was to protect American industries from foreign competition. TheSouth opposed the tax, because it had no industry to protect. Its chief productwas cotton, which was exported to Europe. The American import taxes forcedEuropean nations to put taxes on American cotton. This meant a drop in the saleof cotton and less money for the planters of the South. It also meant higherprices in the American market for manufactured goods. South Carolina refused topay the import tax. It said the tax was not constitutional, that theconstitution did not give the federal government the power to order aprotective tax. At one time, the vice president of the United States -- John C.Calhoun of South Carolina -- had believed in a strong central government. Buthe had become a strong supporter of states' rights. Calhoun wrote a longstatement against the import tax for the South Carolina legislature. In it, hedeveloped the idea of nullification -- cancelling federal powers. He said thestates had created the federal government and, therefore, the states had thegreater power. He argued that the states could reject, or nullify, any act ofthe central government which was not constitutional. And, Calhoun said, thestates should be the judge of whether an act was constitutional or not.

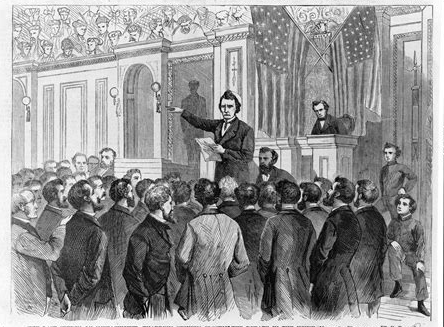

Calhoun'sidea was debated in the Senate by Robert Hayne of South Carolina and DanielWebster of Massachusetts. Hayne supported nullification, and Webster opposedit. Webster said Hayne was wrong in using the words "liberty first, andunion afterwards." He said they could not be separated. Said Webster:"Liberty and union, now and forever, one and inseparable." No onereally knew how President Andrew Jackson felt about nullification. He made nopublic statement during the debate. Leaders in South Carolina developed a planto get the president's support. They decided to hold a big dinner honoring thememory of Thomas Jefferson. Jackson agreed to be at the dinner. The speecheswere carefully planned. They began by praising the democratic ideas ofJefferson. Then speakers discussed Virginia's opposition to the alien andsedition laws passed by the federal government in seventeen-ninety-eight. Nextthey discussed South Carolina's opposition to the import tax. Finally, thespeeches were finished. It was time for toasts. President Jackson made thefirst one. He stood up, raised his glass, and looked straight at John C.Calhoun. He waited for the cheering to stop. "Our union," he said,"it must be preserved." Calhoun rose with the others to drink thetoast. He had not expected Jackson's opposition to nullification. His handshook, and he spilled some of the wine from his glass.

Calhoun was called on to make the nexttoast. The vice president rose slowly. "The union," he said,"next to our liberty, most dear." He waited a moment, then,continued. "May we all remember that it can only be preserved byrespecting the rights of the states and by giving equally the benefits andburdens of the union." President Jackson left a few minutes later. Most ofthose at dinner left with him. The nation now knew how the president felt. Andthe people were with him -- opposed to nullification. But the idea was not deadamong the extremists of South Carolina. They were to start more trouble twoyears later. Calhoun's nullification doctrine was not the only thing thatdivided Jackson and the vice president. Calhoun had led a campaign against thewife of Jackson's friend and secretary of war, John Eaton. Three members ofJackson's cabinet supported Calhoun. Mister Calhoun and the three cabinet wiveswould have nothing to do with Mister Eaton. Jackson saw this as a politicaltrick to try to force Eaton from the cabinet, and make Jackson look foolish atthe same time. The hostility between Jackson and his vice president wassharpened by a letter that was written by a member of President Monroe'scabinet. It told how Calhoun wanted Jackson arrested in eighteen-eighteen.

The letter writer, William Crawford, was inthe cabinet with Calhoun. Jackson had led a military campaign into SpanishFlorida and had hanged two British citizens. Calhoun proposed during a cabinetmeeting that Jackson be punished. Jackson did not learn of this untileighteen-twenty-nine. Jackson wanted no further communications with Calhoun. Severalattempts were made to soften relations between Calhoun and Jackson. One of themseemed to succeed. Jackson told Secretary of State Martin van Buren that thedispute had been settled. He said the unfriendly letters that he and Calhounsent each other would be destroyed. And he said he would invite the vicepresident to have dinner with him at the White House. With the dispute ended,Calhoun thought he saw a way to destroy his rival for the presidency --Secretary of State Martin van Buren. He decided not to destroy the letters heand Jackson sent to each other. Instead, he had a pamphlet written, using theletters. The pamphlet also contained the statement of several persons denyingthe Crawford charges. And, it accused Mister van Buren of using Crawford to tryto split Jackson and Calhoun. One of Calhoun's men took a copy of the pamphletto Secretary Eaton and asked him to show it to President Jackson. He told Eatonthat the pamphlet would not be published without Jackson's approval. Eaton didnot show the pamphlet to Jackson and said nothing to Calhoun's men.

Calhoununderstood this silence to mean that Jackson did not object to the pamphlet. Sohe had it published and given to the public. Jackson exploded when he read it.Not only had Calhoun failed to destroy the letters, he had published them.Jackson's newspaper, the Washington Globe, accused Calhoun of throwing afirebomb into the party. Jackson declared that Calhoun and his supporters hadcut their own throats. Only later did Calhoun discover what had gone wrong. Eaton had not shown the pamphlet to Jackson.He had not even spoken to the president about it. This was Eaton's way ofpunishing those who treated his wife so badly. Jackson continued to defendMargaret Eaton's honor. He even held a cabinet meeting on the subject. All thesecretaries but John Eaton were there. Jackson told them that he did not wantto interfere in their private lives. But, he said it seemed that their familieswere trying to get others to have nothing to do with Mister Eaton. "I willnot part with John Eaton," Jackson said. "And those of my cabinet whocannot harmonize with him had better withdraw. I must and I will haveharmony." Jackson said any insult to Eaton would be an insult to himself.Either work with Eaton or resign. There were no resignations. But the problemgot no better. Many people just would not accept Margaret Eaton as their socialequal. Mister van Buren saw that the problem was hurting Jackson deeply. But heknew better than to propose to Jackson that he ask for Secretary Eaton'sresignation. He already had heard Jackson say that he would resign as presidentbefore he would desert his friend Eaton.