Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION – American history in VOA Special English. Franklin Pierce was elected the fourteenth president in eighteen fifty-two. He was forty-eight years old, one of America's youngest presidents. Pierce was the compromise candidate of the Democratic Party. He won the nomination on the forty-ninth ballot at the party's convention. He then won a big victory in the general election over the candidate of the Whig Party, General Winfield Scott. One of Pierce's friends, the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, helped him with his campaign. This week in our series, Steve Ember and Shirley Griffith talk about the presidency of Franklin Pierce.

Franklin Pierce was from the northeastern state of New Hampshire. He was a lawyer and former state lawmaker. He also had served in the United States Senate and House of Representatives. He became an officer in the Army during America's war with Mexico in the late eighteen forties. Pierce had been a public official for more than twenty years when he became president. Yet he was not a strong leader. He also faced a difficult situation in his personal life. Two of his children had died when they were babies. A third child was killed in a train accident shortly before Pierce was inaugurated. In addition, his wife Jane did not like the city of Washington. She did not support her husband's campaign for president. Years earlier, she had urged him to resign from the Senate and return to New Hampshire. She did not want to go back to Washington, even to be first lady. When her husband was elected, she agreed to live there. But she rarely saw anyone. One of her close friends took her place at public events. Franklin Pierce was a young man. And his inauguration speech was about a young America. He promised strong support for expanding the territory of the United States. He also promised a strong foreign policy.

In his foreign policy, President Pierce successfully negotiated with Britain to gain American fishing rights along the coast of Canada. However, he was unsuccessful in an attempt to buy Cuba from Spain. One of the most important developments in foreign policy during Pierce's administration actually began earlier. Former president Millard Fillmore had sent Navy Commodore Matthew Perry to Asia. Perry finally sailed into Tokyo Bay in eighteen fifty-three. His arrival led to the establishment of diplomatic and trade relations between the United States and Japan. National issues presented President Pierce with more difficult decisions. The Compromise of eighteen fifty had settled the dispute over slavery in the western territories. But it did not end slavery. There was still a chance that the North and South would go to war over the issue. Another question linked slavery and the western territories. Where should the United States build its new railroads. As America grew and white settlers moved west, many felt a great need for good transportation. They wanted railroads that reached across the continent from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. Engineers decided that four new rail lines would be possible.

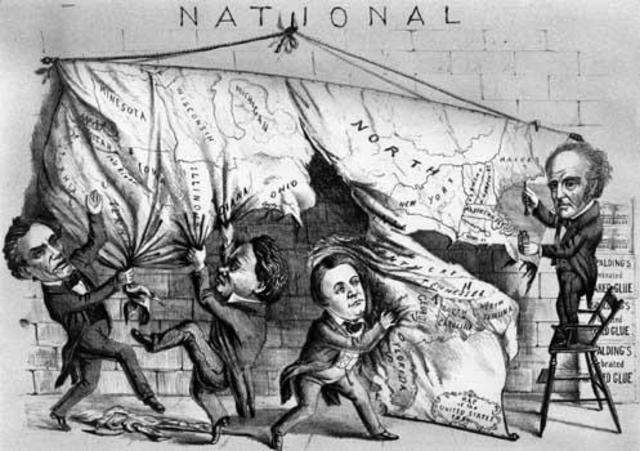

One could cross the northern part of the country, connecting the cities of Saint Paul and Seattle. Another could cross the middle, connecting Saint Louis and San Francisco. A third could connect Memphis and San Francisco. And a fourth could be far to the south, connecting New Orleans and San Diego. Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois proposed that three lines be built. He said the government could give land to the railroad companies. The companies could then sell the land to get the money they needed to build the lines. A Senate committee discussed the situation. It decided that building three railroads at the same time would be too difficult. It proposed that only one be built. But which one? Many congressmen believed that a southern line would be best. There would be little snow in winter. And the railroad would cross lands already organized as states or official territories. A northern or central line would face severe winter weather. And it would have to cross a wild area called Nebraska. Nebraska was neither a state nor a territory. In trying to settle the question of railroads, the issue of slavery rose once again. Nebraska lay north of the Missouri compromise line, which had been established in eighteen twenty. Slavery was not permitted there. The state of Missouri lay next to Nebraska. Missouri was a slave state. Slave-holders in Missouri did not want the Nebraska area to become a free territory. They were afraid their slaves would flee to it. They felt threatened by the free states and free territories all around them.

For years, Congressmen from Missouri had defeated all attempts to make Nebraska an official territory. When Congress met in eighteen fifty-three, it considered a new bill on Nebraska. Instead of creating one large territory, the bill would create two. The northern part would be called the Nebraska territory. The southern part would be called the Kansas territory. The proposal to split them was called the Kansas-Nebraska bill. The bill did not clearly say if slavery would be legal, or illegal, in the two new territories. The purpose of the Kansas-Nebraska bill reportedly was to settle differences among opposing railroad interests in the area. Yet many Americans believed the real purpose was to permit the spread of slavery. A group of anti-slavery Senators denounced the bill. They said it was part of a southern plan to spread slavery wherever possible. They also said it was being used by Senator Stephen Douglas for political purposes. They said he was trying to gain southern support for himself in the next presidential election. When the Senate began debate on the Kansas-Nebraska bill, Stephen Douglas was the first to defend it.

Douglas said the bill would give people in the Kansas and Nebraska territories the right to decide if slavery would be permitted. He said the same right had been given to people in New Mexico and Utah by the compromise of eighteen fifty. And he said that same right was meant for people of all future territories. In the past, he noted, the national government had tried to divide free states from slave states by a line across a map. He said a geographical line was not the answer. He said the people of a state or territory had the right to decide for themselves. Douglas argued that the compromise of eighteen fifty took the place of the earlier Missouri compromise of eighteen twenty. The new Kansas-Nebraska bill, he said, simply recognized the fact that the Missouri compromise was dead. Opponents of the Kansas-Nebraska bill quickly rejected the Senator's argument. They said Douglas was not honest in his statements about the eighteen fifty compromise. True, they said, the compromise gave the people of Utah and New Mexico the right to decide about slavery. But they said it did not give that right to the people of all future territories.

Opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska bill was extremely strong in the northern United States. In city after city, big public meetings were held. Businessmen organized many of the meetings. They were angry at Senator Douglas because he had re-opened the dispute about slavery. They feared that the dispute would hurt the economy. Northern churchmen also united against the Kansas-Nebraska bill. Thousands signed protests and sent them to Congress. Senator Douglas criticized the churchmen. He said they should stay out of politics. In the southern United States, the Kansas-Nebraska bill caused little excitement. Most southerners were not greatly interested in it. They believed it might help the cause of slavery. But they also believed it might lead to trouble. Senate debate on the bill continued for more than a month. Senator Stephen Douglas was sure it would be approved. We will continue the story of the Kansas-Nebraska bill, and the administration of President Franklin Pierce, next time.