Researchers Study Spiders' Silks to Make New Materials

Cheryl Hayashi began examining the body of a silver garden spider under her microscope.

Using two sets of tweezers, she soon found what she was looking for: hundreds of silk glands, the organs spiders use to make their webs.

Each gland lets a spider produce a different type of silk.

"They (spiders) make so many kinds of silk!" Hayashi said. "That's just what boggles my mind."

Hayashi's lab at the American Museum of Natural History is studying the genes behind each kind of silk. She has collected spider silk glands of about 50 species.

The goal is to make a kind of "silk library," she said. The library could become an important information resource for designing new products from space equipment to clothing.

However, the library's work is far from complete. There are more than 48,000 spider species known worldwide.

Spider silks all start out in the same way: as a wet and sticky substance. It is like rubber cement or thick honey, as Hayashi describes it. Spiders make the substance and store it in a gland until they want to make silk.

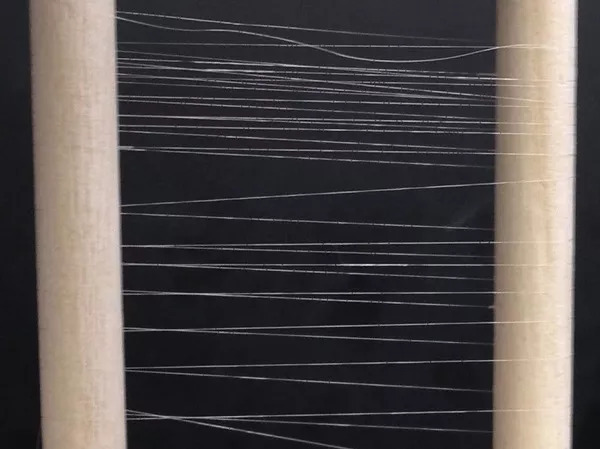

Then, a short tube called a spigot opens. As the substance flows out, it changes into a solid silk strand that joins with other strands coming from other spigots.

Nobody knows how many kinds of spider silks exist. But, some species can produce many kinds. Orb-weaving spiders, for example, make seven kinds.

Hayashi has been studying spider silk for about 20 years. Only recently has improved technology let scientists quickly study the genetic material, or DNA, of spiders and produce synthetic spider silk in large amounts.

Until recently, scientists had to first cut the glands' DNA into pieces. They then used a computer to try to put the DNA back in order, like a jigsaw puzzle. The task is especially difficult for the DNA of spiders because their genes are very long and repetitive.

That is the problem Sarah Stellwagen from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County faced. She was studying genes, and DNA, related to spider silk. She thought she could do it quickly, but it took almost two years.

Scientists have to recover the full gene to truly copy natural silk, she said. If they try to produce silk from only part of a gene or something produced in a laboratory, "it's not as good as what a spider makes," Stellwagen said.

It was only last year that a research group was able to make a small amount of silk that perfectly matched the kind of silk that an orb-weaving spider dangles from. But that was only one kind of silk from one species.

Hayashi asked: "What about the other 48,000?"

As technology has improved, researchers can now map genes much better without first chopping them up. And companies have gotten closer to successfully recreating spider silks.

Now, the task remains to discover the secrets of the thousands of other spider silks out there, which is not easy.

"But hey, you know, we all have goals," Hayashi said.

I'm John Russell.