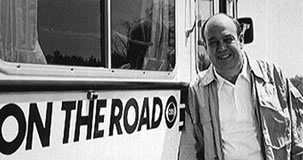

Our story today is called "Wanderlust". It was written by American reporter Charles Kuralt. It is from his book "A Life on the Road". The word "wanderlust" means a strong desire to travel. For many years Mr. Kuralt traveled across America, telling interesting stories about Americans. His reports were broadcast on the CBS television network. In the beginning of his book there is a poem by Scottish writer Rubber Lewis Stevenson. It describes Mr. Kuralt's Wanderlust. It says "Wealth, I ask not; hope, nor love; nor a friend to know me. All I ask, the heaven above and the road below me." In the following story Charles Kuralt tells how he began his traveling life. Before I was born I went on the road. The road was highway seventeen. It went from the city of Jacksonville to the city of Wilmington in North Carolina. That is where the hospital was. My father backed the car out of his place in the barn. He helped my mother into the front seat. It was 1934. My father made the trip to Wilmington in little more than an hour. He hardly slowed down for stop signs in the towns along the way. I was born the next morning with traveling in my blood. I had already gone 80 kilometers.

We lived on my grandparents' farm for a while during the Great Economic Depression of the 1930s. There was a sandy road in front and a path through the pine trees behind. I always wondered where the roads went. After I learned that the one in front went to another farm, I wondered where it went from there. In back, playing among pine trees I once surprised some wild turkeys. They went flying down the path and out of sight. I remembered wanting to go with them. My mother was a teacher. My father had planned to become a big business man, but he became a social worker instead. He helped poor people. He got a job with the state government. His job took us from one town to another. I loved every move. I began to find out where the roads went. Since my mother was busy teaching school, somebody had to take care of me. The answer to the problem caused a little trouble for my father, I imagine, but it was perfect in my opinion. He took me with him on his trips. As we rode along the country roads, my father told me stories. We stopped in the afternoons to fish for a few minutes in little rivers turned black by the acid of cypress trees. We stopped in the evenings to eat meals of pork, sweet potatoes and grains. Then we rode on into the night, looking for a place to sleep. Just the two of us, rolling on in a cloud of friendly company and smoke from his cigar. I wanted never to go home from these trips.

Charles Kuralt's story continues with memories of his early travels. I entered contests that promised travel as a prize. When I was twelve I won one of these competitions. It was a yearly baseball writing contest organized by a newspaper. The prize was a trip with the Sharlat Honits, the local baseball team. Another boy and I traveled with the team to games in Ashfel, North Carolina and Noxfel, Tennessee. I loved being away from home in places I had only heard about. I loved being with the players and listening to them talk. Best of all, I loved writing about the game on an old typewriter I had borrowed from someone in my father's office. I was only 12, but I tried to sound like I had been doing this for years. After that summer I wrote about basketball and football games for the school newspaper. I became, in my imagination, an experienced traveling reporter. I was not old enough to drive a car to the games. Sometimes I had to ride in the backseat of my parents' car where the children always sat. I accepted the situation by making up stories there in the backseat. I imagined I was really flying across an ocean in an airplane, looking over my notes for a big story while on the way to Constantinople or Khartoum.

When I was 14, I won another contest and got another trip. This time it was a speaking contest called the Voice of Democracy. As one of four winners from the United States, I got to give my speech in Williamsburg Virginia, the capital of Virginia when Virginia was still a British colony. From Williamsburg we went to Washington to meet President Harry Truman at the White House. Mr. Truman treated us like adults for which I was thankful. But I knew I was not really a White House reporter yet, because the woman holding my arm and smiling nervously was my mother. I could not wait to grow up and be off on my own. On the dirt roads near our house I learned to drive a car. My father sat beside me again in the passenger's seat this time. I was not old enough to get the official document that would permit me to drive by myself. I asked my parents to tell state officials that I was older. "We could go to jail for that." my father said. I said, "Nobody would ever find out." In the end my father agreed. It was the only real lie he ever told. So I had my driver's license. Naturally the first thing I did was plan a trip. My friend and I got an old car. Someone had repaired it with parts from different kinds of cars. It was a mix, a kind of Shavie Ford mobile. We got an old radio, too. It would not fit in the normal place on the control board, so we hung it from a wire underneath. That summer with parts clashing and radio swinging we had it for California.

Our idea was to explore the Rocky Mountains and west coast, perhaps go north into Canada and end up at North Western University in Illinois. I was supposed to attend a summer writing program for high school students at the university. We traveled slowly to save fuel and because we had promised our worried parents that we would not drive fast. We quickly learned that we had overestimated everything: the ability of our vehicle, the distance we could travel in a day, the amount of money we needed and our desire to be away from home. We thought that we would never make it to California. Instead we crossed the Mississippi River with our money and our spirits running low. We were having arguments about small things. We were having a crisis of inexperience. We made it to Chicago. My friend got a job selling hot dogs to pay for his trip home alone. I got a room and waited for the start of my class. At last came the day when I took the train to the university. I remembered not one thing I might have learned in the next 6 weeks of the writing program. I do remember walking on the college grounds and watching sail boats in the distance on the blue waters of Lake Michigan. I remembered a coffee shop where students talked and laughed. The streets and walks and grass and buildings of the university seemed to me a Hollywood version of a college. And I seemed to myself a big boned boy from the South, a country boy after all.

I wanted to gain at least a little of the social experience I saw all around me. But I did not know where to begin. Then the summer ended and it was too late. I took the train part way home. Then I stood on the side of the road, trying to catch a ride, the rest of the way. One day I got a ride in the back of a truck. I returned the wave of a man who stood up from his work in his vegetable garden to watch us pass. I saw a woman hanging wet cloth on a rope to dry in the sun. The road passed under and away from me, kilometer after kilometer. I was perfectly happy. In one sleepy town the truck driver stopped. I went into the court house to find a toilet. I looked into offices and saw people at work at typewriters and adding machines. I felt terribly sorry for them. They were going to work there at their desks all that day and the next and the next and half a day on Saturday. They would return to those same desks and office machines on Monday morning. I walked out of the building, climbed into the back of the truck again and left the town behind. The sun was shining and I could feel the wind in my hair.