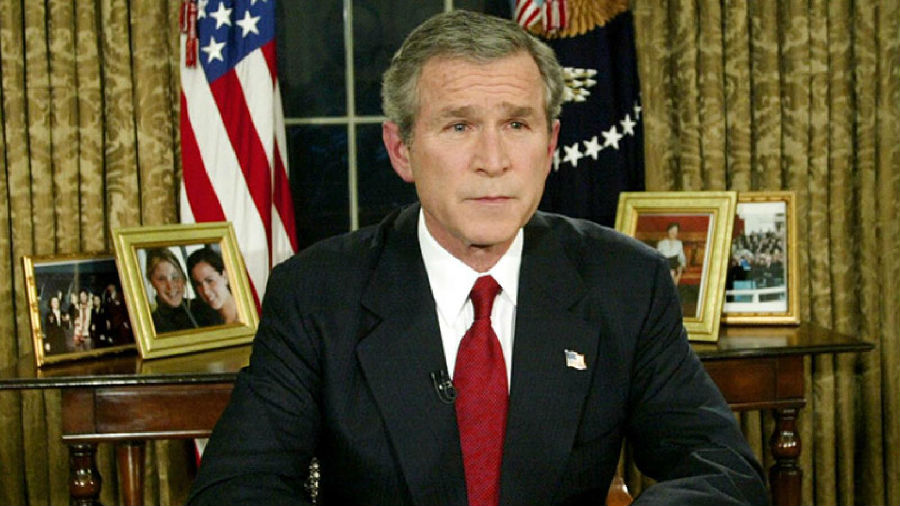

Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION – American history in VOA Special English. I'm Steve Ember. This week in our series, we continue the story of the presidency of George W. Bush. George W. Bush began his second term -- and fifth year in office -- in January two thousand five. Early in his first term, terrorists had carried out the worst attacks in United States history. President Bush declared a war on terror and led the country into wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. In his second inaugural address, he promised to continue fighting to defeat terrorism and increase democracy around the world. "So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world." He also talked about his goals at home and what he called America's ideal of freedom. "In America's ideal of freedom, citizens find the dignity and security of economic independence instead of laboring on the edge of subsistence. This is the broader definition of liberty that motivated the Homestead Act, the Social Security Act, and the GI Bill of Rights...

"We will widen the ownership of homes and businesses, retirement savings, and health insurance, preparing our people for the challenges of life in a free society. By making every citizen an agent of his or her own destiny, we will give our fellow Americans greater freedom from want and fear and make our society more prosperous and just and equal." The United States Constitution limits presidents to two terms. Presidential historian Russell Riley at the University of Virginia's Miller Center says presidents traditionally use their first term to focus on their major goals for the country. Second terms, he says, "tend to be unhappy times." During his second term, Richard Nixon resigned over the attempt to hide political wrongdoing in the Watergate case. Bill Clinton faced a trial in the Senate over his attempt to hide a relationship with a young aide. But the first major problem of George Bush's second term dropped from the sky. "You saw people on the rooftops. You saw people using claw hammers trying to break through their attic to get up onto their roof. That's why you had so many people who drowned." In August of two thousand five, Susan Bennett received a phone call from her daughter, a television reporter in New Orleans, Louisiana.

"She called, on a Friday, and said, 'I think you need to come pick up my son, because there's a really big storm coming.'" It was Hurricane Katrina -- one of the worst natural disasters in American history. Along the Gulf of Mexico the hardest hit states were Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. Over one thousand eight hundred people died. Property damage totaled more than seventy-five billion dollars. But Katrina will be remembered mostly because of what happened in New Orleans. A day before the storm hit, officials had ordered everyone to leave the city. But thousands of people stayed. Some chose not to leave. Others were too poor, too old or too sick to go. Then, the levees broke. Those flood barriers were supposed to protect the city. Much of New Orleans was built on land that lies below sea level. As Katrina hit, more than eighty percent of the city flooded. In some areas, the water was six meters deep. Many people who stayed were caught in the floods. Officials struggled to get food, water and medicine to the survivors. The displaced included thousands of people who took shelter in the Superdome, a big sports arena. Out on the streets, lawless acts fed a sense of disorder and helplessness.

"It's disgusting and frustrating. And we are human beings, and they're treating us like we're criminals." "We want help! We want help! Help us!" Susan Bennett helped create an exhibit about Hurricane Katrina at the Newseum, a museum of news in Washington. "Not only in this country, but also in newspapers across the world, you saw the same headline. It ranged from 'Engulfed' to 'Our Tsunami.' 'Chaos.' And then it went to 'Anarchy,' 'National Disgrace.'" Congress later found that officials at every level of government -- local, state and federal -- had failed in doing their jobs. President Bush flew over New Orleans to inspect the damage. A photograph showed him looking out the window of Air Force One at the ground below. Russell Riley at the University of Virginia says the picture expressed what many people were thinking about the handling of the disaster. "Because of the ineffectiveness of the government response at the time, that image communicated to the American people that the president was remote. That he wasn't on the ground. That the best he could do was just look out the window of a passing plane." In two thousand five a different kind of storm was hitting Iraq. American and Iraqi officials were struggling to create a democratic government. Local militias were on the rise and attacking coalition forces and other Iraqis.

The violence also included al-Qaida suicide bombings in Iraq, which angered many Iraqis. And there was international anger as the result of photos that showed American troops abusing Iraqi prisoners. President Bush had declared the end of major combat operations on May first, two thousand three. That was less than two months after the invasion. But the numbers of civilian and military deaths were growing. And, in the United States, surveys were showing that a growing number of Americans thought going into Iraq was a mistake. "The bad news was we were uncomfortable with it, and we wanted to get out, and we could not understand how things could go so terribly wrong." Judith Yaphe joined the National Defense University after twenty years as a Middle East expert at the Central Intelligence Agency. "That's where the lack of strategy and the mismanagement come in. But I think it's also true that, you know, Americans just wanted to say, 'Why are we in Iraq? Why are we in any of these places?' Because, historically speaking, it's not a role we've been comfortable with."

She says by President Bush's second term, few Iraqis wanted to cooperate with the Americans to make the country more secure. But President Bush said American troops could not leave until Iraqi forces replaced them. In two thousand six, an Iraqi court sentenced the country's former leader to death. Saddam Hussein was hanged for crimes against humanity. But nothing else seemed to change -- violence and insurgent attacks continued. Early the next year, President Bush announced that he was sending more troops to Iraq. He thought it would help stop the violence. "These troops will work alongside Iraqi units and be embedded in their formations. Our troops will have a well-defined mission – to help Iraqis clear and secure neighborhoods, to help them protect the local population, and to help ensure that the Iraqi forces left behind are capable of providing the security that Baghdad needs." The temporary increase of about thirty thousand troops came to be called "the surge." In September of two thousand seven, the top commander in Iraq reported to Congress that the violence was decreasing. The surge may have helped create the conditions for this change but there were other reasons as well. Middle East expert Judith Yaphe says many Iraqis decided to work with the Americans to defeat the insurgency.

"The real truth is – and it's a good news story – that the Iraqis themselves saw that this was a greater danger to them, that there was nothing to be gained, the Sunnis of Iraq in particular, saw that al-Qaida was hurting them, that it was a danger to them, that there was much more to be gained by aligning with the US forces." By the time President Bush was finishing his second term, Iraqi and American officials had agreed on a withdrawal date to end the war. The last American forces would leave Iraq by the end of twenty-eleven. Russell Riley at the University of Virginia says it is too soon to know how history will judge the United States' actions in Iraq. "If Iraq proves to be a policy success, then the surge will be a critical turning point and a terrific exercise of presidential leadership." He also points out that the war is not the only measure by which the forty-third president will be judged. Professor Riley put it this way: "The great debate among historians will not be whether Bush was a powerful president or consequential president, but whether he directed those powers in the most fruitful way that he could have."

So, what else was going on in the United States during this period? Millions of people were voting for which singer should get a recording contract on "American Idol." Year after year it was the most popular show on television. "Oh, Robert, I think you just killed my favorite song of all time." "Killed in a good way or a bad way?" "Killing is never good. There's never a happy killing." "I'm sorry to hear that." "No, that was first degree on that one." But the biggest story in music was not what people were listening to, but how. Sales of CDs in stores fell as more and more people downloaded songs from the Internet. On iTunes, Fergie's "Big Girls Don't Cry" was the most downloaded song of two thousand seven. For the first half of the decade, there seemed to be nothing to cry about in the American housing market. Home prices were going up and up, which made sellers happy. And lenders were offering bigger and bigger loans at easy terms and low interest rates, which made buyers happy. The government supported the easing of lending rules as a form of social policy, a way to help more people buy homes. Rates of home ownership -- a part of the American Dream -- reached record highs. In two thousand five nearly seven out of ten Americans owned their own home.

But many home buyers had been given mortgage loans that they could not afford to pay back. And that was not the only problem. Banks had been selling those loans as securities to investors around the world. Everyone thought they were getting a good deal -- the banks, the borrowers, the investors. But then the price bubble burst and the housing market collapsed. Many borrowers lost their homes because they were unable to make their monthly loan payments. That was the situation Karen Lucas and her husband, of Cleveland, Ohio, found themselves in. "I've done my crying. I've made my peace, and I put it in God's hands." As home values fell, many people found themselves "underwater," meaning they owed more on their mortgage than their house was worth. Suddenly there was a lot to cry about. By the end of two thousand seven, the economy was sliding into the Great Recession. That -- and the election of two thousand eight -- will be our story next week.