Books and Arts; Book Review;Algeria and France;War by any other name;

文艺;书评;阿尔及利亚与法国;冠以他名的战争;

Algeria: France's Undeclared War. By Martin Evans.

《阿尔及利亚:法国未承认的战争》。作者马丁·伊凡斯。

In 2006 Francois Hollande, now the Socialist Party's candidate in France's forthcoming presidential election, declared “in the name of the Socialist Party” that the Section Francaise de l'Internationale Ouvrière, the forerunner of his party, “lost its soul in the Algerian War. It had its justifications but we still owe an apology to the Algerian people.”

2006年,弗朗瓦索·奥朗德,当前法国即将到来的总统大选的社会党候选人,宣称“工人国际法国分部”,他的党派的前身,“在阿尔及利亚战争中丧失了灵魂。这场战争有正当的理由但我们依旧欠着阿尔及利亚人民一个道歉。”

Indeed so. It was a Socialist prime minister, Guy Mollet, who in 1956 ordered a campaign of “pacification” against Algeria's nationalists. Opposed to colonialism, Mollet may well have acted out of good intentions, but “pacification” amounted to repression and countless acts of brutality and torture by the French army.

的确如此。正是社会党的总理盖伊·莫勒在1956年下令对阿尔及利亚的民主主义者采取“和谐”运动。反对殖民主义的莫勒很可能出于好心,但法军执行的“和谐”只相当于镇压和数不清的暴行和折磨。

But Martin Evans, a British academic, is too good an historian to present a one-sided story of Algeria's quest for independence. The insurgent Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) was ruthless in its determination to be the sole representative of Algerian nationalism, willing to kill and maim not just French settlers but also the rival nationalists of Messali Hadj's Mouvement National Algérien. The cruelty was exercised even within the FLN's own ranks, witness the cold-blooded strangling of Abane Ramdane or the assassination of Mohamed Khider, another of its leading figures.

但马丁·伊凡斯,一位英国学者,作为一位优秀的历史学家不会只单方面描写阿尔及利亚追求独立的故事。叛乱的“民族解放阵线”(FLN)为实现其成为阿尔及利亚民族运动的唯一代表的野心可谓冷酷无情,不只是愿意杀害和重伤法国移民,就连对民族主义阵营的竞争对手,梅萨丽·哈吉的“阿尔及利亚民族运动组织”也是如此。这种残忍甚至也在FLN的内部等级中践行,参见其对刺杀了FLN领袖人物穆罕默德·海德尔的阿班·拉姆丹实行的冷血绞刑。

Mr Evans's title reminds the reader that the Algerian conflict was officially only a “police operation”. Recognition that it was a full-scale war, France's worst conflict since the second world war, came only with a vote by the National Assembly in 1999, some 37 years after Algeria's independence. But the thoroughness of this book is that it traces the origins of the war all the way back to the French invasion of 1830. What followed were dismal decades of discrimination, poverty and famine.

伊凡斯的头衔提醒读者,阿尔及利亚的争端官方来说只是一次“警务行动”。一直到阿尔及利亚独立37年之后,才随着1999年国民大会的投票承认“这是一场彻底的战争、法国自从二战以来最严重的一次冲突”。但这本书的透彻之处在于,它将战争的根源一路追溯到了1830年的法国入侵。随之而来的是充斥着种族歧视、贫穷和饥荒的黑暗的数十年。

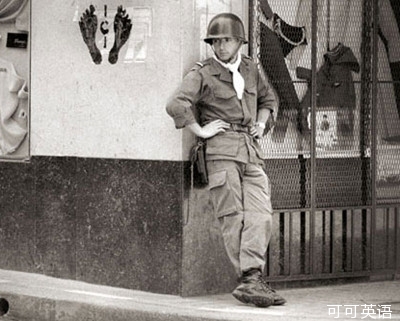

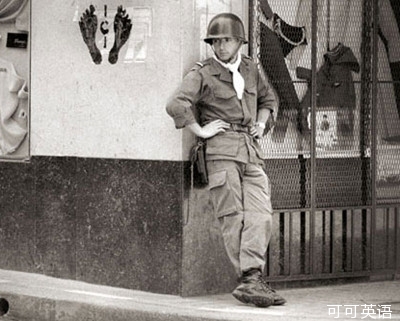

In retrospect, it is hard to see how metropolitan France could ever have imagined a secure and peaceful hold on “French Algeria”. Once the war erupted, there was never much hope that France's politicians, from Mollet through to Charles de Gaulle, could win Muslim Algerian “hearts and minds”. Nor could they win the trust and support of the European settlers, the pieds noirs (literally “black feet”, see picture above) whose sense of betrayal led them to side with the futile rebellion against de Gaulle by the dissident French soldiers of the OAS (Organisation de l'Armée Secrète).

回顾过去,很难明白大国法兰西何以幻想能安全和平地掌控“法属阿尔及利亚”。自从战争爆发,法国政治家从莫勒到查尔斯·德·高尔,从来就没有什么希望能赢得阿尔及利亚穆斯林的“衷心和理解”。他们也不可能赢得欧洲移民的信任和支持,法国侨民(字面为“黑脚”,见上图)的背叛意图让他们与异见的OAS(Organisation de l'Armée Secrète)法国士兵一同站在了对抗德·高尔的无望的反叛军一方。

As Mr Evans describes, it was not just Algeria's history that militated against it being an inseparable part of the French nation, but also the context of contemporary geopolitics. The tide of anti-colonialism after the second world war was forcing Europe's imperial powers to grant independence almost everywhere. France had already been defeated in Vietnam; Britain's prime minister Harold Macmillan talked of the “wind of change” sweeping across Africa; and America's President Eisenhower swiftly compelled France (which accused Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser of aiding the FLN), Britain and Israel to pull back from their 1956 seizure of the Suez Canal. The implications were recognised by de Gaulle: if France were to be a power to be reckoned with in a world now defined by the cold war, it had to rid itself of the Algerian millstone—whatever the objections of the settlers who would then have to seek refuge in France.

正如伊凡斯描述的,不仅是阿尔及利亚的历史阻止其成为法国不可分割的一部分,同样也有当前的地缘政治环境的影响。二战之后的反殖民主义浪潮迫使欧洲的帝国主义势力承认几乎所有殖民地的独立。法国已经在越南被打败;英国首相哈罗德·麦克米兰谈到席卷非洲的“变幻之风”;美国总统艾森豪威尔迅速强迫法国(该国指控埃及的贾麦尔·阿卜杜勒·纳赛尔资助FLN)、英国和以色列从他们1956年控制的苏伊士运河撤回。德·高尔读出了这些暗示:如果法国要在我们今天称为冷战时期的世界作为一个大国得到认同,就必须放下阿尔及利亚的包袱·不管移民如何抱怨,都不得不到法国寻求庇护。

But what of today? Mr Evans's excellent book is marred only by the occasional editing error (ORAF, the Organisation of the French Algerian Resistance, exists only as an acronym, and Mr Evans, when talking of the founding members of the European Economic Community, omits the Netherlands). It ends with a somewhat depressing postscript chapter.

但今日何如?除了偶尔出现的笔误(ORAF,法属阿尔及利亚抵抗组织,在书中只以缩写出现,并且伊凡斯在说到欧洲共同市场的创立成员国的时候省略了荷兰),以及这本书以一个稍微令人沮丧的后记章节收尾。伊凡斯优秀的著作可谓瑕不掩瑜。

In France, citizens of Algerian and other north African descent are disproportionately poor and discriminated against; at times their young, caught between two different cultures, react with violence, as in the urban upheavals of 2005. As Mr Evans says: “The riots of 2005 were just one example of how the legacy of the Algerian war is still being played out.” Meanwhile, in Algeria itself, the country struggles with the aftermath of another undeclared war: the brutal repression by the army of the Islamist forces who two decades ago were about to be voted into office.

在法国,阿尔及利亚以及其他北非族裔的公民不成比例地贫穷和受到歧视;有时他们的年轻一代,夹在两种不同的文化之间,会以暴力的方式应对,正如2005年的城市暴动那样。正如伊凡斯所说:“2005年的骚乱只是阿尔及利亚战争的遗留的延续。”同时,在阿尔及利亚本土,该国也挣扎于另一场未承认的战争:军队对二十年前即将通过投票进入政府的伊斯兰势力的残酷镇压。