Finance and Economics;Europe in limbo;Home and dry

The joke recounted by the boss of a large Italian bank is an old one, but it captures the moment. Two hikers are picnicking when a bear appears. When one laces up his boots to run, his friend scoffs that he can't outrun a bear. The shod hiker retorts that it is not the bear he needs to outrun, merely his fellow hiker. “We're sitting at the picnic with our boots still on,” says the bank boss.

一家意大利大银行老板讲了一个笑话,虽然笑话老掉牙了,但是正切合现在的状况。两名背包客正在享受野餐,一只熊出现了。其中一个立刻穿上靴子准备逃命,他的朋友却嘲笑他不可能跑得过熊。前者却反驳道,他不用跑得过熊,只要跑得过他的同伴就够了。这个银行老板说:“我们现在就是穿着鞋子野餐。”

As policymakers and pundits try to work out the effects of a Greek exit, banks and investors have already been taking precautions. One course of action has been to pull money out of more fragile markets. Never mind the weakest economies like Greece, Ireland and Portugal; Spain and Italy have also lost foreign bank deposits of about 45 billion Euro(56 billion dollar) and 100 billion Euro respectively from their peaks. Add in things like sales of government bonds by foreigners (see chart 1), and capital flight is probably equal to about 10% of GDP in those countries, say Citigroup analysts. Such outflows are hard to stop.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has filled this funding gap by providing liquidity to the banks. But that has in turn reinforced the second precautionary tactic: matching assets and liabilities within countries as much as possible. It is a common refrain from bankers that the euro area no longer functions as a single financial market, although that has the paradoxical advantage of making a break-up less destructive. Banks have used ECB loans to borrow from the national central banks of the countries in which they have assets; that should mean that both sides of the balance-sheet would get redenominated in the event of a euro exit.

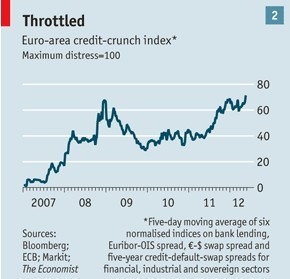

Much of that ECB liquidity is meant to find its way into the real economy, of course. But the third precautionary technique, for both lenders and borrowers, is to hang fire while uncertainty is so high. The Economist has compiled credit-crunch index, comprising a number of measures on everything from bank lending to the cost of buying insurance against default for banks, firms and sovereigns in the euro zone. A single index disguises big differences between weaker and stronger states, but it shows that credit is crunchier now than it was at the height of the banking crisis in 2008 (see chart 2).

Much economic activity is being strangled as a result. In Spain firms have put bond issues and asset sales on hold. Volatility makes it almost impossible to value an asset, bankers say. The Catalan government failed to sell 26 buildings in Barcelona earlier this year for about 450m Euro because one of the bidders wanted to introduce a clause that said rents would be paid in dollars in the event of a euro break-up; the other bidder pulled out because it had been told by headquarters to hold off on deals in southern Europe.

The number of Spanish companies filing for bankruptcy climbed by 21.5% in the first quarter. Nearly a third of these were in the property or construction industries, but the rot is spreading. Alestis, an aeronautical supplier to aircraft manufacturers, filed for bankruptcy earlier this month after failing to reach an agreement with banks to refinance its debts.

The sound of credit crunching can also be heard next door in Portugal, where loans to non-financial companies fell by 5% in the first quarter compared with the same period last year, and credit to households by 3.6%. One of the conditions of the country's bail-out programme is that banks should reduce their total loans to 120% of assets. The quickest way to do that is to avoid making loans.

Conditions are little better in Italy. The province of Varese, near Milan, is a manufacturing heartland: its factories make plastics, textiles and a range of engineering products. Once firms there griped about poor infrastructure and red tape; now the credit squeeze is their main complaint. The local bosses' association says that 40% of firms were hit by lowered borrowing ceilings between January and March, and 15% were told to pay back loans. Banks turned down 45% of requests for new funding.

Those loans that are extended carry hefty interest rates, in part because higher sovereign-borrowing costs have a knock-on effect on banks' funding costs. Differences in sovereign rates can be self-reinforcing, especially when German firms across the border are rivals. “A marginal northern Italian company competing against an equal company in Bavaria will go bust,” says the boss of one bank. “Then the cost of risk goes up and has to be shared by all the other small companies.”

If firms cannot borrow from banks they lengthen payment terms to their suppliers, exacerbating the credit problem, says Michele Tronconi of Sistema Moda Italia, a body representing textiles and clothing firms. Fashion is Italy's second-largest export industry, but no sector has a higher level of non-performing loans.

This credit squeeze will have tightened since Greece's inconclusive election this month. That further dents growth prospects: estimates by Now-Casting, a forecasting firm, suggests that euro-zone GDP will contract by 0.2% in the second quarter. That in turn risks worsening the debt dynamics of the zone's peripheral countries at just the wrong time. Policymakers keep trying to buy time to solve the crisis, but they may be only speeding the end they are trying to avoid.