社会舞台上的社会阶层

Charlie and the aspiration factory

查理和巧克力工厂

Why British theatre is obsessed with social mobility

为何英国戏剧如此痴迷社会流动性主题

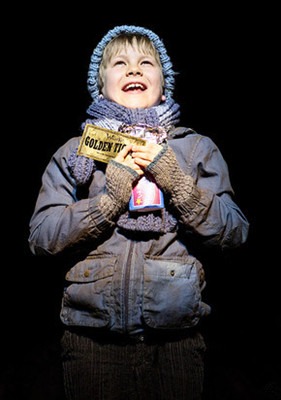

THERE are several ways of retelling “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory”. In 2005 Hollywood focused on Willy Wonka, the factory's owner, portraying him as a purple-gloved man-child. A new musical production of Roald Dahl's children's story at the Theatre Royal in London concentrates on the up-from-poverty fortune of Charlie Bucket, the boy who finds the golden ticket. Mr Wonka lurks in beggar's dress at the side of the stage, as if selecting a specimen for a social experiment.

《查理和巧克力工厂》有好多个复述版本。2005年的好莱坞版从工厂主威利·王卡下手,剧中他是一位带着紫色手套,充满孩子气的男子。伦敦皇家剧院新上演的罗尔德·达尔儿童故事音乐剧则侧重于表现穷孩子查理发现金券,脱贫的经历。在该剧中,王卡衣着褴褛如乞丐隐藏着自己的身份,好似要选一个标本做社会实验。

Tales of upward social mobility attempted or achieved are crowding the London stage. “Billy Elliott”, the story of a miner's son who contends with bereavement, strikes and the north-south divide to make it as a ballet dancer, recently celebrated its four-millionth visitor. “Port”, an account of a Stockport girl's attempts to escape her girm origins, was a success at the National Theatre this spring. Last year “In Basildon” depicted strivers in the quintessential upwardly-mobile Essex town.

伦敦舞台上充斥着各种尝试或成功转为上流社会的故事。舞动人生,最近刚迎来它四百万访问者,它讲述的是一个关于一个矿工儿子不顾家人的反对,社会罢工及南北的分裂,毅然选择成为芭蕾舞者的故事。Port,关于一个斯托克波特女孩试图摆脱其悲惨出身的故事,在国家剧院热映取得巨大成功。去年上映的《在巴斯尔顿》描述的是一群奋斗者在埃塞克斯镇—一个典型的向上爬人群的小镇。

It is a venerable theatrical (and literary) theme, but it is being handled in a different way. John Osborne's 1956 play “Look Back in Anger” showed a working-class man's fury at the middle class he had married into. By the 1970s and 1980s writers were looking down their noses at social climbers, in plays like “Top Girls” and “Abigail's Party”, in which a middle-class arriviste serves cheesy nibbles and the wrong kind of wine.

这是个可敬的戏剧艺术主题,它却以不同的方式呈现出来。约翰·奥斯本的1956年的剧本《愤怒中回顾》呈现的是一个通过婚姻,一个工人阶级转变为中产阶级,处于中产阶级他的不满与愤怒。20世纪七八十年代,作家们着眼于眼前的向上爬的社会群体,戏剧《巅峰女孩》,《阿比盖尔的政党》中产阶级暴发户就像低劣的老鼠,不合时宜的红酒。

Social mobility receded as a topic for a while, as playwrights like David Hare turned to scrutinising the state of the nation. Now it has returned—and is depicted much more sympathetically. Dominic Cooke, who directed “In Basildon” at the Royal Court Theatre, says this may be a delayed reaction to the collapse of state socialism in Europe. Left-wing writers can no longer look to an alternative ideal. Instead they focus on how people navigate British society.

当剧作家诸如戴维海尔等转身开始审视国情,向上层社会爬的话题才稍微退热。而今,这个话题又成为热议,并且现在更多地是表现出一种同情。在皇家宫廷剧院上演的戏剧《在巴斯尔顿》的导演多米尼克这样说道,这也许是国家社会主义在欧洲崩溃的延迟效应。左派作家无法寻求到另一个理想,于是他们将目光投向人们如何操纵英国社会。

A possible reason for the sympathetic tone is that upward mobility can no longer be taken for granted. In 2011 researchers at the London School of Economics concluded that intergenerational social mobility, assessed by income for children born between 1970 and 2000, had stalled. Another study, by Essex University academics, found matters had not improved during the slump.

也许出现这种同情的语调还有另一个原因,那就是向上层社会爬不再是种理所当然的想法。2011年,伦敦经济学院的调查人员通过评估1970至2000年为孩子存储的收入,总结道:两代人的社会流动性停滞不前。另一项由埃塞克斯大学学者进行的研究发现各项问题并没有在经济衰退期得到改善。

So it is fantastic fun to see people make it. Charlie Bucket does so spectacularly. At the end of “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” he is a pint-size entrepreneur, with an immigrant workforce of Oompa-Loompas to ensure he does not tumble back down the social ladder.

所以看看人们演绎它也很有趣。查理令人啼笑皆非。 在“查理和巧克力工厂”的结局,他是一个小型的企业家,有一群奥古伦伯人在巧克力工厂工作,以确保他永远不会从社会的楼梯中跌落下来。 翻译:朱玲 校对:周洋