In 1994 he blamed his personal coach for giving him a power drink full of American chemicals. As for his hobnobbing with the Camorra crime syndicate at Napoli, he considered them protectors and nice people, who gave him gold Rolexes and seemed to want nothing in return. But then he never had much of a handle on his business affairs. He left those to others, while he had fun. In other ways Napoli showed him at his best. He went to a poor, volatile southern city, scorned by the rich north, and won major trophies for it, the first it had ever had.

1994年,他指责他的私人教练给了他一杯富含美国化学物质的强力饮料。至于他在那不勒斯与卡莫拉犯罪集团的交往,他认为他们是保护者和好人,他们给了他镶有黄金的劳力士,似乎什么回报也不想得到,但后来他对自己的生意从来就没怎么处理过。他让别人来处理问题,他自己去享受,在其他方面那不勒斯展示了他最好的一面。他去了一个贫穷,动荡的南方城市,被富庶的北方所鄙视,并因此赢得了重大奖杯,这是它有史以来第一次。

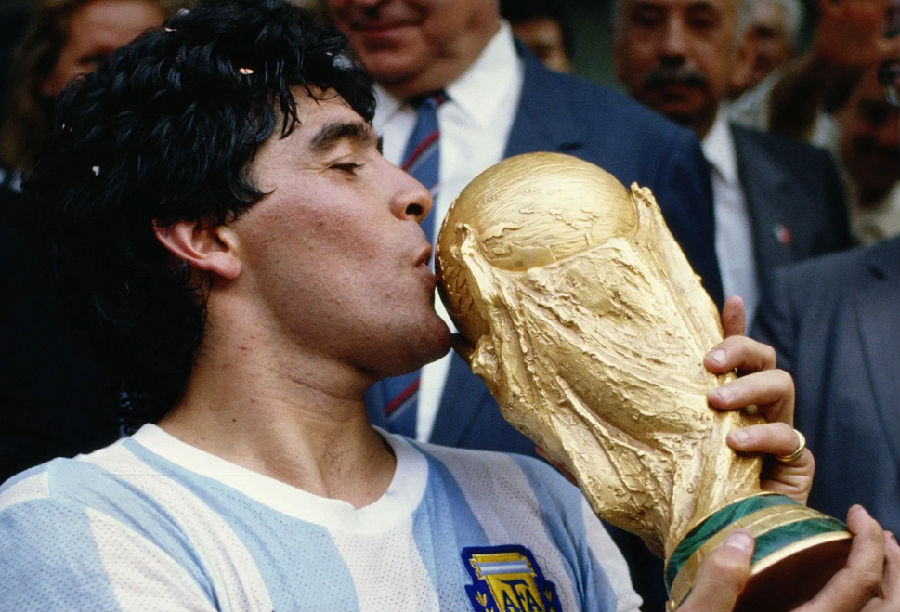

He was revered as a saint for restoring its pride by thrashing everybody else. And of course he had done that first in Argentina, idolised like God himself for salving with his brilliance the loss of the Malvinas and the junta years. Yet winning the World Cup, he mused as he came home, had not brought down the price of bread. Only politicians who spoke for the masses could do that. So he was both a Peronist and a chavista;

Fidel Castro (whose beret he begged from him) was tattooed on his left leg, Che Guevara on his right arm. He told the pope that he should sell the Vatican's gold ceilings to feed the poor. As he grew stouter and sicker, he coached the national side and returned as director of Boca Juniors, the team he had most wanted to play for as a boy. His aim stayed just the same, to bring joy to people with a ball. He was el Diego de la gente, the people's player. And despite the force of the kick that Villa Fiorito had given him, up to the stars, he still felt he had those corduroy trousers on, the old pair he always wore, winter and summer.

译文由可可原创,仅供学习交流使用,未经许可请勿转载。