Turns out, scorpions don't taste so bad -- though eating them is more about texture than flavor. They do impart a satisfying crunch.

事实证明,蝎子并没有那么难吃──虽然吃蝎子更多的是质感而非味道上的体验。咀嚼它们,的确能给人带来一种令人满足的嘎吱嘎吱的响声。

I was with my husband and three children in Li Qun, a roast-duck and fried-insect restaurant in a back alley of a rundown hutong -- a neighborhood of traditional courtyard houses -- in Beijing. The only 'facility' was a hole in the ground down the block, but still, on the walls of the restaurant hung photos of famous visitors: Jet Li, Al Gore.

当时,我和丈夫及三个孩子在利群──一家位于北京一条破旧胡同后巷、供应烤鸭和炸昆虫的餐馆。胡同是传统四合院住宅的街区。那儿唯一的“厕所”就是街区尽头地上的一个洞。尽管如此,在这家餐馆的墙上还是挂着造访此处的知名人士的照片:李连杰和前美国副总统阿尔・戈尔(Al Gore)。

My two eldest kids, 10 and 8, were determined to have some dining escapades in China. In the Wangfujing night market, we'd seen live, shoe-size arthropods impaled on sticks, ready to be cooked, but the yuck factor was insurmountable. At Li Qun the bugs were an inch long, dipped in batter, and deep fried, making them just palatable enough. In a video we made, my 10-year-old, Gideon, plucks a crispy critter from a bed of rice crackers, pops it into his mouth and swallows. 'Tastes just like cockroach!' he exclaims. Then he entreats me to crunch a scorpion for posterity. And because my family was in Asia to do what good travelers around the world do -- push ourselves outside our comfort zone -- I did.

我最大的两个孩子分别为10岁和8岁,他们决定在中国进行一些饮食文化上的冒险。在王府井夜市上,我们看见了串在签子上、鞋子大小的活的节肢动物正等着下锅,但难吃、令人恶心的因素令我们难以逾越。在利群餐馆,那些虫子有一英寸长(约合2.5厘米),浸入面浆后再充分油炸,这样就使它们吃起来够美味。在我拍摄的一段视频中,我10岁的儿子吉迪恩(Gideon)从一堆米饼上撕扯下一块脆皮虫身、扔进嘴里然后咀嚼起来。他大叫道:“尝起来就像是蟑螂!”然后,他恳请我为子孙后代咬一只蝎子。因为我的家人在亚洲做了全球各地的好游客都会做的事──将我们自己推出舒适区──所以我就吃了。

Beijing is not the most obvious destination to visit with children. The traffic is murder, the smog so bad locals wear face masks and the tap water isn't potable. 'It's so dirty,' a Chinese-American friend back home warned; we should time our trip to avoid spring's dust storms, someone else suggested. But our children had just completed their first year of Chinese-immersion school in New York, and after months of research, we concluded that the capital might be more kid-friendly than it seems.

带着孩子出行游玩,北京并不是最明显、最合适的一个目的地。那里的交通状况真要命,雾霾严重、以至于当地人都得戴面罩,而且自来水也不能直接饮用。一位华裔美国人朋友从北京回来以后警告我说“那里太脏了”;另一个人则建议我们要安排好旅行时间、避开春季的沙尘暴。但我们的孩子才刚刚在纽约上完了第一年的浸入式中文课,而且在经过数月的研究后,我们得出结论,首都北京比它表面上看起来更适宜儿童。

In Beijing, the ancient is constantly butting heads with the modern. Songs, Mings, Qings and many other dynasties ruled China from the city, over the centuries erecting the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace and the Great Wall. Now those icons have competition from attractions like the $140 million National Aquatics Center -- or Water Cube -- and the National Stadium (aka the Bird's Nest), built for the 2008 Olympics.

在北京,古典与现代一直在持续碰撞。宋、明、清及其他许多朝代都在此地建都、统治中国,数百年来,紫禁城、颐和园与长城也在北京一一建成。如今,一些新兴名胜──如耗资1.4亿美元、为2008年北京奥运会而建的国家游泳中心(或被称为水立方)及国家体育场(又名鸟巢)──与上述那些标志性古迹展开了竞争。

Our stint in Beijing capped off a two-week visit to eastern China, most of it spent in tiny villages and holiday spots unfamiliar to Americans. Remote Lands, which specializes in custom tours of Asia, did most of the planning, booking hotels, transfers and many activities. With the bulk of the logistics taken care of, we had space for serendipity and discovery.

我们在北京短暂逗留后,便进行了一次为期两周的华东之行,其间,我们大多数时间都住在了美国人不太熟知的小村庄和度假景点。远陆(Remote Lands)是一家专注于亚洲定制游的旅行公司,它为我们做好了大部分的计划、订酒店、安排交通出行以及许多活动。由于大部分的后勤都已被安排好,我们就有了意外发现珍奇事物和探索的空闲。

In Beijing, we started where everyone else does: in Tiananmen Square, built in 1415 as the royal entrance to the Forbidden City, the imperial palace. The square was thick with Chinese tourists, and to their eyes my family must have been a novelty -- people insisted on taking photos with my blond husband and pulled my 5-year-old daughter, Talia, from her stroller for more shots. (I was invisible; perhaps brown-haired mothers aren't so remarkable.)

在北京,我们从其他每位游客都会选择做为出发点的地方开始游玩:天安门广场。它建于1415年,当时是作为皇室通往皇宫紫禁城的入口。广场上满是中国游客,在他们眼里,我们一家人一定很新奇--人们坚持要跟我金发碧眼的丈夫合影,还把我5岁的女儿塔莉娅(Talia)从她的折叠式婴儿车上拉过来多拍了几张照。(我就是个透明人;可能棕色头发的妈妈不是那么能引人注意。)

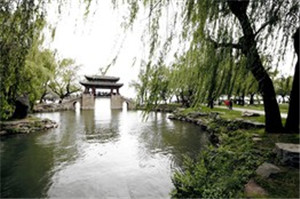

The Forbidden City is beautiful and well preserved, from the gilded lions guarding the Gate of Heavenly Purity to the serene Imperial Garden. The kids recognized the complex from Bernardo Bertolucci's 1987 film, 'The Last Emperor.' But little ones can only take so many halls of thrones and tapestries. ('Where is the princess?' my daughter asked our guide a number of times.) So we went to take a rickshaw ride through courtyard houses yet to be replaced by gleaming condos.

从守卫在干清门的镀金狮子到宁静的御花园,美丽的紫禁城保存完好。孩子们认出了这些建筑群就是导演贝纳多・贝托鲁奇(Bernardo Bertolucci)在1987年拍摄的电影《末代皇帝》(The Last Emperor)中所呈现的场景。但小孩子们也就只能意识到有这么多摆着龙椅和悬着挂毯的大厅,仅此而已。(“公主在哪儿呢?”我女儿问了我们导游好几次这个问题。)于是我们去坐了趟人力车,穿过了一家家四合院,它们现在还尚未被流光溢彩的公寓所取代。

A kind woman let us enter her hutong home, which made up one side of a courtyard. The mistress of the house was so well off, she explained, she did not have to work. My jaded little New Yorkers were baffled. Two rooms for three people? A shared stove -- outside?帝 My husband and I attempted to turn this into a teachable moment, but the kids had moved on and were exclaiming over the mistress's pet cricket.

一位友善的妇女让我们走进了她在胡同里的家,这户人家占据了一座四合院的一边儿。那位妇女解释说,这家的女主人生活相当富足,她都无需工作。这让我们家善嘲讽的小纽约客们感到困惑不已。两个房间要住三个人?共用一个灶--还是在外边?我和丈夫本想试着把此时此刻变成教育孩子们的好时机,但他们却已开始往前走并朝着女主人养的宠物蛐蛐大喊大叫起来。

To work off some of their energy, we raced up the steps of the Drum Tower, a 154-foot-tall structure built during the reign of Kublai Khan. As we arrived, 25 percussion students entered the hall, and in perfect unison pounded the hell out of 6-foot-wide drums. We had to rush off to an hour-long date that Remote Lands had scheduled with a master kite-maker. In his tiny kitchen, he taught the kids to make miniature kites by heating sticks of bamboo over a candle until they were pliable, then gluing on sheets of rice paper. Rain had cleared the sky of smog and the streets of muck, and in the quiet hutong, my children flew their painted masterpieces -- a butterfly, a dragon and a bird.

为了让他们消耗点儿精力,我们比赛跑上了鼓楼的台阶。这座高154英尺(46.7米)的建筑修建于忽必烈统治时期。当我们到那儿的时候,正赶上25名打击乐团的学生走进大厅,他们的乐器击打声与猛击六英尺(约1.8米)宽的鼓形成了完美的和鸣。我们还得急着赶去另一个时长一个小时的约会,那是远陆(Remote Lands)旅行社为我们安排的与一位风筝制作大师的会面。在大师狭窄的厨房里,他教了孩子们制作微型风筝:将竹棍置于烛火上烤,直到它变得柔韧易弯,然后糊上一张宣纸。雨水洗刷了天空中的雾霾,冲掉了街上的尘土污泥,在宁静的胡同里,我的孩子们放起了他们画出来的杰作--一只蝴蝶,一条龙和一只鸟风筝。

At a corner store, while my husband took snaps of a ramshackle soda display, our 8-year-old, Malachi, reached into a basket for a tart yogurt drink he'd come to love. He took a sip from the straw, then made a sour face. 'Someone already drank it!' he yelled. Using their broken Mandarin, the children learned from the shopkeeper that Malachi had pulled the bottle from a recycling basket.

在一间位于拐角的店铺里,当我丈夫在抓拍一字摆开的苏打水时,我们8岁的儿子玛拉基(Malachi)将手伸进了一个篮子中、够到了一瓶酸奶饮品--他觉得自己会非常喜欢喝。他用吸管吸了一口,然后一脸酸相。“这瓶有人喝过了!”他喊道。孩子们用蹩脚的中文从店主那里得知,那个瓶子是玛拉基书从废物回收的篮子里拣出来的。

We morbidly joke that Malachi's last words will be 'Hold my beer and watch this.' But he does make our family more intrepid. At the Wangfujing night bazaar, a street swarming with food stalls, tchotchke booths and shoe peddlers, he bought a ceramic 'tea boy' that was supposed to urinate once filled with hot water; when it didn't work, he negotiated for a new one. He convinced fruit vendors to let him try one of everything. At the Summer Palace, imperial gardens that date to the mid-1700s, he ignored guards' warnings to stop rock-hopping along the edge of a lake. What did he care -- he was 7,000 miles from home!

我们病态地开玩笑说,玛拉基的临终遗言将会是“帮我拿一下啤酒,看看这个。”但他确实让我们一家变得更加勇猛无畏了。在一条街满是小吃摊、小玩意儿地摊和卖鞋小贩的王府井夜市上,他买了一个本应该在加满热水后就开始尿尿的陶瓷制品“茶壶男孩”;结果因为不能用,他又去跟卖家周旋换了一个新的。他还说服了水果小贩,获准可以把每一种水果都拿一个尝尝。在18世纪中期修建的皇家园林颐和园中,他也无视保安的警告--不要沿着湖边跳过石头。他才不管呢,他在乎的是--他在距家7000英里(约合11,265公里)远的地方!

And unlike at home, in China we adopted some of his attitude. We jumped down the stairs of the ancient Bell Tower, across the street from the Drum Tower; we crashed a wedding reception at the Raffles Hotel.

不像在家里,在中国的时候我们接受了他的一些态度。我们从古代钟楼的楼梯上跳下来,从鼓楼出来横穿马路;还闯入了莱佛士大酒店(Raffles Hotel)里的一场婚宴。

On our final day in Beijing, a driver took us to one of the best-preserved sections of the Great Wall, Mutianyu. Navigating the market that lined the path from the parking lot took time: Malachi had to bargain for T-shirts, passion fruit and chess sets. (Our matching Communist Youth hats cost $1 each.) On the stairs of the wall, Talia declared, 'I am a great stepper!' though she later clarified that she wasn't the Queen of Walking. I put her on my shoulders as we made our way to the Schoolhouse, a former primary school where artists in residence can now blow glass or paint, and students learn to grow organic produce and cook it in the property's restaurants.

在北京的最后一天,一位司机载我们去了长城保存最完好的一段:慕田峪。从停车场出来,经过的道路两边都设有市场,从市场里寻路走过去花了我们不少时间。玛拉基得砍价买T恤、西番莲果和国际象棋棋具。(我们那些正好合乎脑袋大小的共青团帽每顶卖一美元。)在长城的阶梯上,塔莉娅宣布称:“我是名伟大的登高者!”尽管之后她又澄清道,自己真的不是徒步女王。在去小园餐厅(Schoolhouse)的路上,我就把她顶在自己肩上。这里曾经是所小学,现在居住于此的艺术家们则可以吹玻璃或者作画,而学生们也可以学习种植有机农产品并在其附属的餐厅里烹饪它们。

We scanned the menu at one, called the Canteen; there were no scorpions to be had. Across the brick courtyard, I made eye contact with another foreign mom. She winked and raised her glass. At that moment I was certain that, despite the language barrier, despite the used yogurt, despite the sometimes hectic schedule, seeing Beijing through my children's eyes was worth the inconveniences. And where else would I have the guts to eat a scorpion again?

我们不约而同地扫视了一下菜单,给餐厅打了电话;这里没有蝎子可以吃。透过砖瓦建成的四合院,我的目光与另一位外国母亲两两相对。她朝我眨眼示意并举起了玻璃杯。那一刻,我非常确定,尽管存在语言障碍,尽管酸奶已被人喝过,尽管行程有时匆忙紧凑,但让我的孩子们用自己的眼睛看看北京,受些罪也值得。再说,这世上还有什么地方能让我有胆量再吃一只蝎子呢?