I've never received a telegram. This realization, when it occurred to me recently, made me feel inexplicably nostalgic.

我从来没有收到过一封电报,一想到这儿,我心里就涌上一股说不清道不明的怀旧愁绪。

There are, after all, plenty of technological rituals in which I've never participated. I haven't taken a daguerreotype, or asked a switchboard operator to connect me to a phone number with letters in it, or fired up a Victrola for some sweet tunes on the ole phonograph.

毕竟我错过了很多科技界的大事件,比如我没有感受过银版照相技术,也没有通过接线员给别人打过电话,更不曾随着手摇留声机里甜美的歌声心绪起伏。

I grew up in an era when cassette tapes, fax machines, and long-distance telephone calls gave way to CDs, emails, and cellphones—only to be supplanted by MP3s, chat platforms, and smartphones. I still write letters. I will neither confirm nor deny having gone through a vinyl phase.

我所在的是一个盒式录音带让位给CD,传真机让位给电邮,长途电话让位给大哥大的时代——然而好景不长,他们后来又被MP3,聊天平台以及智能手机取代了。我依然坚持手写书信,对于黑胶时代已经结束的说法也也不置可否。

But telegrams! I could have sent one. And I didn't seek them out until it was too late. Western Union closed its telegraphy service a decade ago. (“The last 10 telegrams included birthday wishes, condolences on the death of a loved one, notification of an emergency, and several people trying to be the last to send a telegram,” the Associated Press reported of the closure in 2006.) These days, it's nearly impossible—it may actually be impossible—to send one in the United States, even if you try.

但说到电报!我本来能用上它的。只是直到一切都不来及的时候我才想到要发一封电报。西部联盟电报公司十年前关闭了所有电报服务。(“最后传出去的十封电报包括生日祝福、对过世爱人的悼念、紧急情况的通告,还有几封电报是为了成为最后一个发送者而发出的”,美联社在2006年报道西部联盟电报公司关闭服务的新闻里这样说道)。如今,在美国发一封电报几乎是一件不可能—或许我们可以说绝对不可能的事情,即使你很想这样做。

I tried.

我就这样试过。

Sending a telegram in 2016 is not what it was in the 1850s, or even 1950s for that matter.

2016年发电报与19世纪50年代发电报可不是一回事,甚至它与20世纪50年代也大相径庭。

What it was, in the beginning, was astonishing. The telegraph meant that human communication could, for the first time ever, travel faster than humans could carry a message from one place to the next. A wire was faster than a pony or a boat. It was, for all practical purposes, instantaneous. “There is nothing now left for invention to achieve but to discover news before it takes place,” one New-York Herald reporter declared of the telegraph's achievement in 1844.

起初,电报是一件令人十分惊奇的事情。用电报发消息的速度比千里捎书快,电线传输比马不停蹄快。其实它就是一种即时通信。“眼下已经没有什么可发明的了,除非在新闻事件发生前我们就能预料到它”,1884年《纽约先驱报》这样评论电报业的成就。

As in the grand history of technological curmudgeonry, not everyone was dazzled. The New York Times, in 1858, called the telegraph “trivial and paltry,” also “superficial, sudden, unsifted, too fast for the truth.” The writer and cultural critic Matthew Arnold referred to the transatlantic telegraph in 1903 as, “that great rope, with a Philistine at each end of it talking in-utilities!”

纵观科技史,各种科技发明灿如繁星,并不是所有人都买电报的帐。1858年,纽约时报称电报为“微不足道的”,“肤浅的,突如其来的,未经筛选的,发展过快的”。1903年,身为作家以及文化评论家的马修•阿诺德在谈到联通大西洋两岸的电报工程时这样说:“一条大绳子,一头站着个平庸之辈,说些没用的话”!

By then, the telegraph was both well-established and taken for granted. The earliest electric telegraph systems involved numbered needles on a board that, when a transmission came in, pointed to corresponding letters of the alphabet. One such device, along Britain's Great Western Railway, became the first commercial telegraph in the world in 1838.

那时候,发电报已经成了家常便饭。最早的电报系统配备有键盘凿孔机,当有新的电报发来时,收方根据电码表就能确定信息的内容。1838年,这样的一个装备,随着英国西部大铁路漂洋过海,成了世界上最早的商用电报。

The telegraph that set the standard in the United States was an electric device that Samuel Morse was developing around the same time; a system that transmitted electric signals that were then interpreted and handwritten by a human receiver. By the 1850s, a system that automatically printed telegrams was introduced, but humans were still required to help send the message in the first place. In the 1930s, that part of the process became automated, too.

同年,以萨缪尔•莫尔斯发明的电报装置为起点,电报在美国开始了标准化;电报通信业建立起了一套电信号传送、收录员破译、手写记录的系统。虽然19世纪中期开始引进了自动印刷的电报机,但仍然离不开人工发送这一步,最终在20世纪30年代,这一环节也实现了自动化。

Today, you go online if you want to send one, which, sure, is where you go for basically anything you want to do in 2016.

今天,想发电报你就得上网,当然了,这可是2016年,不论想干什么你都离不开网络。

First I tried iTelegram. It cost $18.95 and was supposed to take three to five business days to deliver a message to my editor, Ross, in The Atlantic's newsroom in Washington, D.C. The company says on its website that it operates some of the old networks, like Western Union's, that used to be major players in the telegram game. It plays up the novelty aspect, suggesting a telegram as a good keepsake on someone's wedding day, for instance. It also leans on the nostalgia factor. “The smart way to send an important message since 1844.” Worldwide delivery guaranteed!

首先,我尝试了iTelegram。这封花了我18.95美元的电报,需要三到五个工作日传到我的编辑罗丝的手中,而罗丝在位于华盛顿大西洋月刊的新闻编辑部中工作。iTelegram宣称在他们公司的服务器上运营着一些过去的网络,比如西部电信联盟这样的业界老大。他们把电报包装成了新鲜玩意儿,比如可以在婚礼上把电报作为一种独特的纪念,也可以用来表达一种怀旧情怀。“1844年后,用电报发送重要消息成了一种巧妙的方法”。尽情享受你的全球交付保证吧!

Three weeks passed, and my telegram still had not arrived. My Slack messages (the modern equivalent of a telegram, I suppose) to Ross had gone from: “Keep your eyes peeled for a telegram!” to “Did you ever get my telegram?” to “still no sign of the telegram!?” to “telegrams, not that impressive, actually.”

然而三周过去了,我的电报迟迟没有送到。我的整合集成消息(在我看来是电报的一种现代等效物)从“睁大你的眼睛看呀,这可是电报!”到“你收到我的电报了吗?”到“我的电报还没到!?”最好变成了“好吧,这东西也没什么大不了的”。

“Telegram Stop relies on the services of Standard International Postal Networks for delivery,” the email I received read. “For unforeseen reasons the delivery via the USPS has been delayed.”

“Telegram Stop依赖于国际标准邮政网络进行投递。”我收到的电子邮件说。“美国邮政管理局的投递工作由于一些未知的原因而延迟了。”

Which is funny, really, because it turns out—and I should have appreciated this sooner, I know—I wasn't sending a telegram at all. I was, apparently, sending a letter that looked like a telegram, first over the Internet and then by the postal service. Which, because I had already received a digital preview of the telegram when I ordered it, I could have just emailed—or texted, or Facebook messaged, or, you know, published to the Internet in an article for The Atlantic.

这还真是好笑,因为其实我根本就没有发出一封真正的电报——我知道,应该早点儿意识到这一点的。明显我只是先通过互联网然后通过邮局寄了一封看起来像电报的信而已。因为我在发送电报的时候就已经拿到了一个电子版的预览,我完全可以直接给电报的收件人发email或者短信,或者facebook私信,要么干脆给大西洋月刊投个稿,把想说的话写成文章直接发布在网上。

Sorry you never received this telegram, Ross. (Adrienne LaFrance)

罗丝,很抱歉你一直都没收到电报。(艾德丽安•法朗仕)

My message, naturally, features some old telegram humor. (The salutation is actually a telephone joke.) “What hath god wrought,” is what Morse transmitted over an experimental line from Washington to Baltimore in 1844, and what's widely celebrated as the first telegraphic message in the U.S. These words were, according to numerous 19th-century accounts, suggested to Morse by Annie Ellsworth, the young daughter of the federal Patents commissioner. Annie got the idea from her mother. (The line originally comes from the Old Testament's Book of Numbers.)

我在信息的内容上耍了一些古老的电报小把戏。(其实是货真价实的电话玩笑)。1844年,一条莫尔斯电报通过华盛顿的实验线路传到了数英里外的巴尔的摩:“上帝创造了什么”,后来人们广泛认为这是美国历通信史上的第一条电报。根据19世纪相关资料,这句话是联邦专利局长官的小女儿安妮•埃尔斯沃斯向莫尔斯提出的建议,而这个想法又是安妮从她妈妈那里得来的(原句出自《旧约圣经•民数记》)。

Here is, according to a Morse-code translation website, what the original message would have looked like in Morse code:

根据摩尔斯电码译码网站,这条信息还原成莫尔斯电码以后长这样:

.-- .... .- - / .... .- - .... / --. --- -.. / .-- .-. --- ..- --. .... -

.-- .... .- - / .... .- - .... / --. --- -.. / .-- .-. --- ..- --. .... -

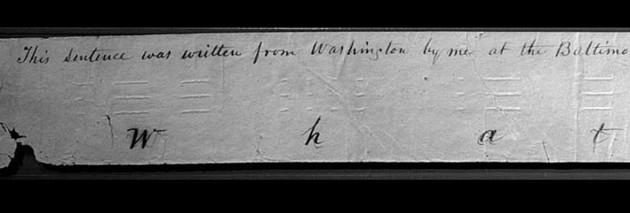

And here's the original paper transmission—with the the message transcribed by hand, though difficult to read—kept by the Library of Congress:

下面是原始的传送稿——上面的信息都是来自手写,很难辨认——现保留在美国国会图书馆。

Here's a close-up:

给个特写:

One curious footnote: There are scattered accounts that argue there were earlier telegraphic messages sent by Morse. A 1923 New York Times article quotes a man who says, citing an anonymous source, that the real first message was sent near Washington Square Park, over a wire from one New York University classroom to another, and that it said, “Attention: The universe. by republics and kingdoms right wheel.”

插个好玩儿的题外话:一些零散的记录显示着有一封比这还早的莫尔斯电报。1923年纽约时报的一篇文章引用了一句来源未知的话,说真正的第一条电报消息是从华盛顿广场公园附近发出来的,这条消息通过电线从纽约大学的一间教室传给另一间,它说:“全世界注意——来自共和国国王的右翼”。

Most of this, I must admit, seems foreign to me. (And not just because I have no idea what that alleged missive refers to, other than the fact that it appears in an 1823 edition of the Niles Register, a popular 19th-century news magazine, as part of an equally perplexing manuscript.) I'm realizing that the more I think about telegrams, the more I learn of them, the stranger they are to me.

我不得不承认,那些东西对我来说太陌生。这不仅因为我搞不懂那些所谓的第一条电报到底说了些什么,还因为我不理解他们为什么会以同样令人费解的面貌出现在1823年的Niles Register(一本风靡19世纪的新闻杂志)杂志上。但我知道我越是想了解更多,越是探究更多,电报这种东西对我来说就越陌生。

I don't know what a telegram sounded like when it arrived, or what the paper felt like in someone's hands. My mind reels to imagine what it was like for journalists who filed their stories by telegraph. I can't read Morse code without the help of an online translator. These are details you can read about, but never truly know without having experienced them—the way I can still hear the shriek of a dial-up modem in my mind when I stop to think about it, or the singsong of Nokia's classic ringtone.

我不知道电报到了是什么声音,也想不出来把它拿在手里是个什么感觉。我满脑子想的都是记者们用它存档稿子时的样子。没有在线翻译我和这些电码完全不来电。这些东西你能从这里读到,但没有经历过的人不会真的懂——即使不去想它,拨号调制调节器滴滴的声音也会在我的脑子里单曲循环,这还没完,有时诺基亚的那只经典的手机铃声也会插播进来(译者注:诺基亚的这个铃声就是莫尔斯电码中MSM,即短信服务的代号)。

All of which is another way of saying: It doesn't really matter whether I sent zero or one telegrams in my life. The tools that characterize a person's time and place in technological history are the ones that a person actually uses, the technologies relied upon so heavily that they can feel like an extension of oneself. This is part of how technology can define a culture, and why sometimes you forget the thing you're using is technology at all. Until, eventually, inevitably, the technology is all but forgotten.

这话还可以换个说法:其实我从小到大有没有发过电报并不重要,因为那些代表了某个时代特征,在浩瀚的科技史上占有一席之地的发明创造,一定是人们切切实实用过的。人们离不开它们,把它们看成自己身体延伸出去的一部分。科技是如何定义文化的,一部分就体现在这里,而你身处其中,有时竟会忘记你一天到晚用着的东西就是科技本身。科技终将被我们遗忘,可在那之前,它无处不在。