5.Aluminum Was More Valuable Than Gold

5.铝比金子还珍贵

Chemists knew that aluminum was around for about 40 years before they had the technology to isolate it. When they finally did so in 1825, it became insanely valuable. Originally, a Danish chemist developed the method for extracting only the tiniest bit, and it wasn't until 1845 that the Germans figured out how to create enough of it that they could study even its most basic properties. In 1852, the average price of aluminum was around $1,200 per kilogram. Today, that's the equivalent of about $33,650.

化学家们在有能力分离铝约40年前就认识了铝元素。在1825年他们终于找到了分离铝的方法,随后铝就变得出奇的珍贵。最初,一位丹麦化学家研究出了一种方法来分离铝,但是只能分离极少的一点。随后在1845年德国人研究出了怎样分离出足够供给的份量,甚至他们可以研究铝的基本属性了。1852年铝的平均价格大约是每千克1200美元,就相当于今天的33650美元。

It wasn't until the 1880s that another process was developed that would allow for the more widespread use of aluminum, and until then, it remained incredibly valuable. The first president of the French Republic, Napoleon III, used aluminum dinner settings for only his most valued guests. The regular, run-of-the-mill guests were seated with gold or silver tableware. The King of Denmark wore an aluminum crown, and when it was chosen as the capstone of the Washington Monument, it was the equivalent of choosing pure silver today. Upscale Parisian ladies wore aluminum jewelry and used aluminum opera glasses to demonstrate just how wealthy they were. Aluminum also formed the backbone of visions for the future. It was the biggest attraction at the Parisian Exposition of 1878, and it became the material of choice for writers like Jules Verne when they were building their grand visions of the future. Aluminum was going to be used for everything from entire city structures to rocket ships. Of course, the value of aluminum took a steep dive when new ways were developed to create it, and it was suddenly everywhere.

直到1880年,技术进步了,铝才被广泛的应用,不过那个时候铝还是贵得难以想象。法国共和国的第一任总统,拿破仑三世只有在宴请最重要的宾客的时候才会使用铝制餐具,一般的普通宾客就用金银餐具招待。丹麦的国王有一顶铝制的皇冠,并且在华盛顿纪念碑的顶点就是纯铝的,就像是我们今天选择纯银是一样的。巴黎上层的贵妇们佩戴着铝制珠宝,并用铝制的观剧望远镜来显示她们有多富裕。铝也构成了未来愿景的骨干。1878年,巴黎举办了一个大型的铝制品展会,一时之间铝成了如凡尔纳等作家在构建未来伟大梦境时的首选材料。那时打算把铝用在从城市建筑到火箭船舶所有可能用到的地方。当然了,当制造铝的新方法出现时,铝突然一下子变得随处可见,其价值也跟着急剧下降。

4.Fluorine's Deadly Challenge

4.致命杀手--氟

The first observations of fluorine came from the 1500s, with a German mineralogist who described it as a material that served to lower the melting point of ore. In 1670, a glassworker accidentally found that fluorspar and acids would react and used the reaction to etch glass. Isolating fluorine proved much more difficult—and deadly.

16世纪一位德国矿物学家开始研究氟,并把它描述为一种能降低矿石熔点的物质。1670年,一个玻璃厂工人偶然发现氟石和酸性物质能够发生化学反应,并将这一发现用于蚀刻玻璃。分离氟也变得越加艰难--还可能致命。

It was our old friend Carl Scheele who determined that it was something in the fluorspar that was causing the reaction, and in 1771, the hunt for fluorine began in earnest. Before it was finally isolated by Ferdinand Frederic Henri Moissan in 1886 (earning him a Nobel Prize), the process left quite a trail of illness and injury. Moissan himself was forced to stop his work four times as he suffered from, and slowly recovered from, fluorine poisoning. The damage done to his body was so great that it's generally thought that his life would have been incredibly shortened by it had he not died of appendicitis only a few months after accepting the Nobel Prize. Humphry Davy's attempts would leave him with permanent damage to his eyes and fingers. A pair of Irish chemists, Thomas and George Knox, also worked extensively on trying to isolate fluorine, with one dying and the other left bedridden for years. A Belgian chemist also died in his attempts, and a similar fate befell French chemist Jerome Nickels. In the 1860s, George Gore's work resulted in a few explosions, and it was only when Moissan stumbled onto the idea of lowering the temperature of his sample to –23 degrees Celsius (–9 °F) and then trying to isolate the highly volatile liquid that fluorine was successfully documented for the first time.

化学界的老朋友卡尔·史基认为这种化学反应是源于氟石里的某种物质。对于氟这一化学物质的寻找之旅也于1771 年正式启程。直到1886年,享利·莫瓦桑才成功将其分离出来,他也凭此荣获诺贝尔奖。然而发现之旅充满了无数的疾病和伤痛,莫瓦桑本人在中途因为氟中毒和缓慢的恢复情况也曾四次被迫停止研究。这一伤害对他的身体影响巨大,以至于人们认为即便亨利没有在得奖几个月后死于阑尾炎,他的寿命也会因此极大缩短。汉弗莱·戴维他的眼睛和手指因研究氟受到了永久性伤害。爱尔兰化学家托马斯和乔治·诺克斯也倾尽全力试图分离出氟,他们一个为此付出生命,一个多年卧床不起。一位比利时化学家也为此付出生命,相同的命运还发生在法国化学家杰罗姆·尼 克尔斯身上。19世纪60年代,乔治·戈尔的研究导致了几起爆炸,直到莫瓦桑误打误撞地想到将他的样本温度降低到-23摄氏度(9°F), 然后尝试着分离高度挥发的液体后,才首次成功获得氟。

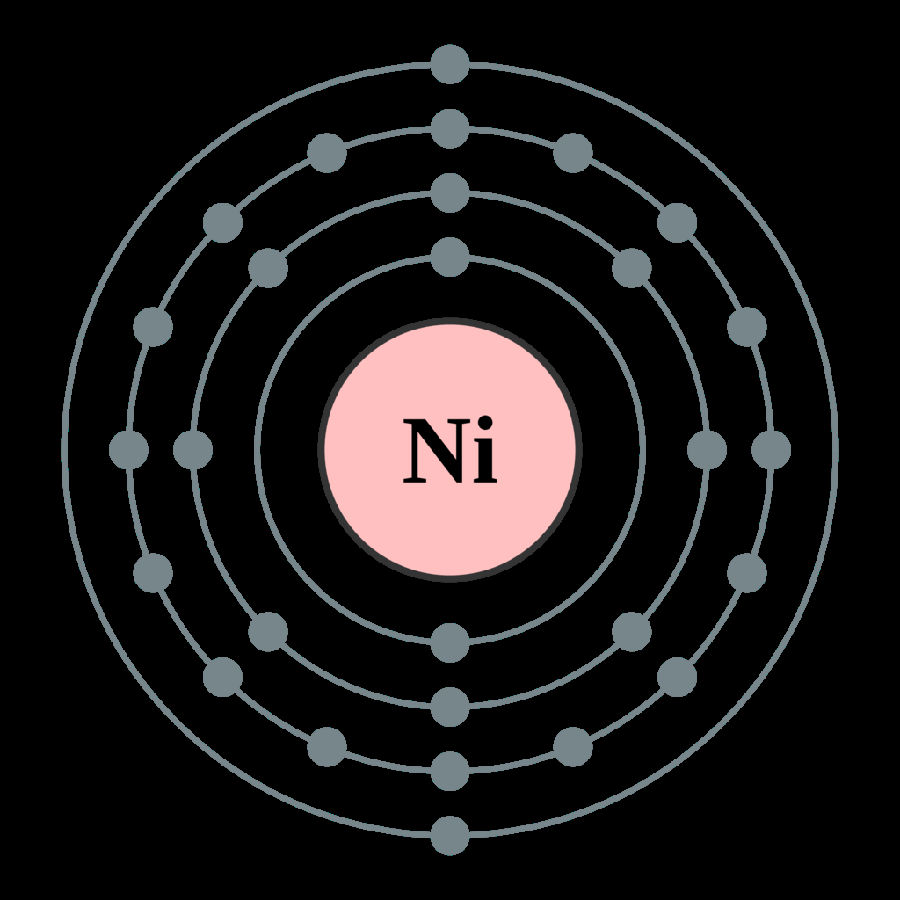

3.The Element Named For The Devil

3.以魔鬼命名的元素

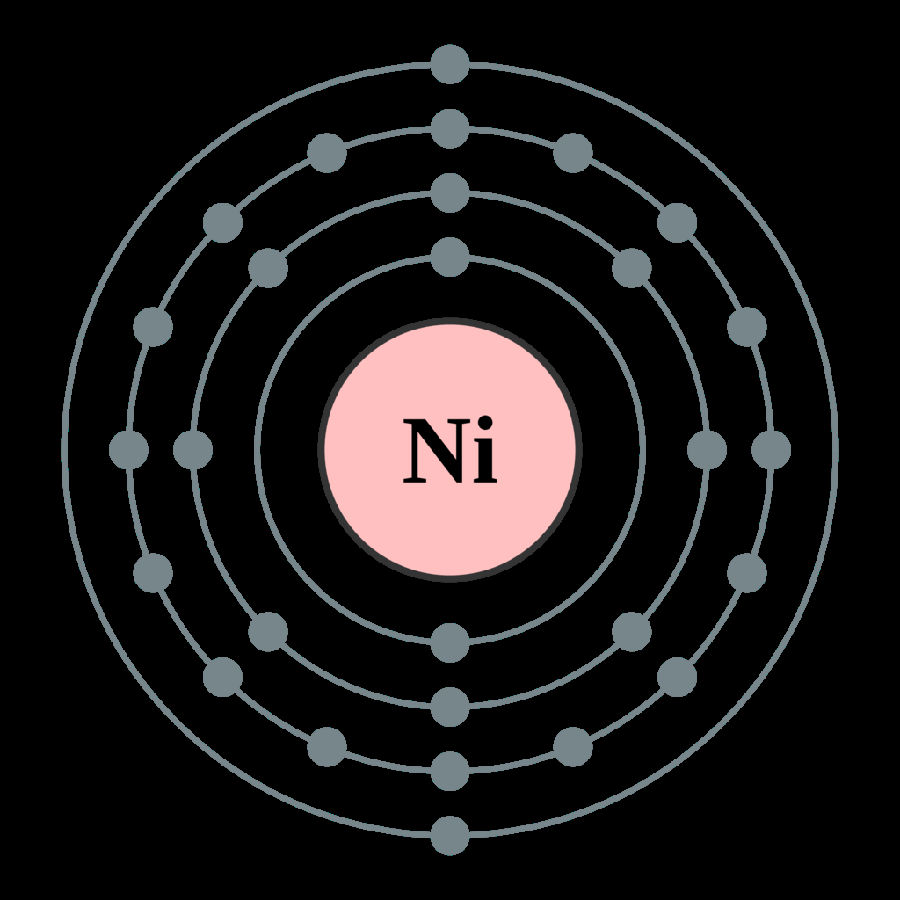

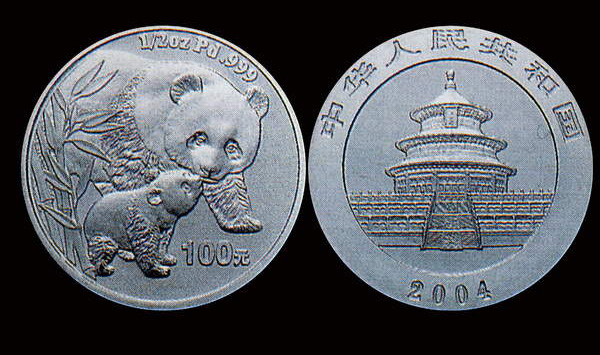

Nickel is incredibly common today, used as an alloy and lending its name to a US coin (that's really only about 25 percent actual nickel). The name is something of an oddity, though. While many elements are named for gods and goddesses, or their most desirable characteristic, nickel is named for the Devil.

镍在现今已经十分普遍,它是美国硬币里的一种合金,正因如此,它也代指美国硬币(不过硬币中的镍含量只有百分之二十五)。不过镍这个名字也挺奇怪的。 其他的元素都是以诸神或他们的特点命名,而镍却是魔鬼的名字。

The word "nickel" is short for the German word kupfernickel. Its use dates back to an era when copper was incredibly useful, but nickel wasn't the least bit desirable. Miners, always a superstitious lot, would often find ore veins that looked like copper but weren't. The worthless ore veins came to be called kupfernickel, which translates to "Old Nick's copper." Old Nick was a name for the Devil, and he was much more than that to the miners who were laboring deep underground. The belief was that Old Nick put the fake copper veins there on purpose, partially to make the miners waste their time and also to guide them in a direction that could be deadly. Every day was potentially deadly, after all, and miners have long believed in the presence of Earth spirits who can either help or kill the interlopers sent into their underground domain. Pure nickel was first isolated in 1751 by Swedish chemist and mineralogist Axel Fredrik Cronstedt, and the name that the miners had been calling the worthless ore for centuries stuck.

"Nickel" 这一单词是德语尼格尔铜的简写。这一用法要追溯到那个铜十分普遍而镍一无是处的时代。那时的矿工们十分迷信,发现几处原以为是铜矿的矿脉,最终却大失所望,这些无用的矿脉就被命名为kupfernickel,翻译成英文就是"Old Nick's copper"。Old Nick是魔鬼的名字。对于在地下深处劳作的矿工们来说Old Nick更为可怕。他们认为Old Nick 故意用假的铜矿来浪费矿工的时间并将他们引向死亡。毕竟,他们工作的每一天都埋伏着死亡的危机,矿工们深信着地灵的存在,坚信地灵可以决定是帮助还是杀死那些进 入其地下领域的入侵者。1751年,瑞典化学家兼矿物学家阿克塞尔·弗雷德里克·克龙斯泰特首次分离出了纯粹的镍。矿工们用了几个世纪的无用矿石这一名字也就此打住。

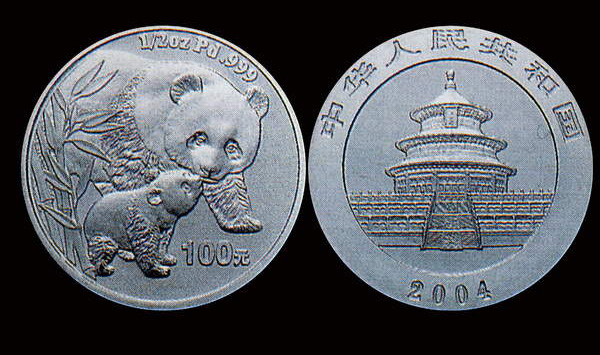

2.The Bizarre Unveiling Of Palladium

2.揭开钯的神秘面纱

Palladium was documented by an incredibly under-studied genius named William Hyde Wollaston. Wollaston, who had a medical degree from Cambridge and only turned to chemistry after a long career as a doctor and inventor of optical instruments, isolated palladium and rhodium and created the first type of malleable platinum. His methods for revealing his finding of palladium to the world make for the best story, though.

钯最先由一位叫做威廉·海德·沃拉斯顿的研究天才所记录的。沃拉斯顿拥有剑桥大学的医学学位,毕业后当了很长时间的医生和光学仪器研究者,之后才从事化学领域的研究,并且成功分离了钯和铑,创造了第一种可延展性铂。他向世人展示钯的方式堪称为化学史上的一朵奇葩。

After establishing a partnership with the financially well-off Smithson Tennant, Wollaston got access to a material that needed to be smuggled into England through Jamaica from what's now Colombia—platinum ore. In 1801, he set up a full laboratory in his back garden and got to work. His journals from 1802 talk about his new element, originally called "ceresium," renamed "palladium" shortly afterward. Knowing that there were other researchers right behind him in their work, he had to go public with his findings. However, he wasn't quite ready to present it formally, so he took a handful of his new element to a store on London's Gerrard Street in Soho. He then handed out a bunch of flyers advertising a wonderful new type of silver that was up for sale. Chemists went rather mad for the whole idea, with a number of them trying to replicate the material and failing to do so. With everyone denouncing the idea that it was anything but some kind of alloy, he anonymously offered a reward for anyone who could prove it. Of course, no one could. In the meantime, Wollaston kept working, found rhodium, and published a paper on it. That was in 1804; in 1805, he was ready to come forward with palladium and wrote a paper on his earlier find. Appearing before the Royal Society of London, he gave a talk on the properties of this strange new material, before summing it up with an admission that he had found it earlier and needed time to explore all of its properties to his satisfaction before making it official.

与经济大亨史密森·坦能建立合作关系后,沃拉斯顿获得了所有实验所需要的原材料。这种材料从现如今叫做哥伦比亚铂矿的地方开采取得,需要从牙买加走私才能进入英国。1801年,他在自己的后花园里建立了一个完整的实验室进行相关研究。沃拉斯顿早在1802年就在日记中提到了他所发现的新元素钯,最初命名为ceresium,不久后改名为palladium。得知还有其他的研究者也在进行相关的研究,他必须尽快公布他的发现。但是,他并不准备按照正常的流程公布,反而将一些新元素给了位于伦敦杰勒德街的一家商店。之后他发了些传单,宣传这是一种待售的新类型优质银。化学家们对这种行为表示气愤,很多人想要剽窃这种材料,无疑全部失败。同时有很多人谴责他,认为这种物质只是一类合金,于是他又匿名宣称任何可以证明这一点的人都将获得丰厚的奖赏。毫无疑问,没人可以证明。但是,沃拉斯顿并没有停止相关的研究工作,在此期间,他又发现了元素铑,并且为此发布了一篇论文。这一切全都发生在1804年。到了1805年,沃拉斯顿准备将钯公之于众,并为此写了一篇关于钯早期发现的文章。在伦敦皇家学会发现该元素之前,他对这种陌生的新材料的性质做了演讲,与向世人公布他早已发现了这种元素相比,成功研究了这种新元素的性质更令他兴奋。

1.Chlorine And Phlogiston

1.氯和燃素

Belief in a substance called phlogiston set back the documentation of chlorine for decades.

人们相信燃素的存在还要追溯要几十年前有关氯的记录。

Introduced by Georg Ernst Stahl, the theory of phlogiston states that metals were made up of the core being of that metal, along with the substance phlogiston. Starting in the 18th century, chemists used it to explain why some metals change substance. When iron rusts, for example, it loses its iron-ness and only has its phlogiston left. The theory was an ever-evolving one, and by the 1760s, it was believed that the substance was "inflammable air," also known as hydrogen. Other elements were referred to in terms of the theory, too. Oxygen was dephlogisticated air, and nitrogen was phlogiston-saturated air. In 1774, Carl Scheele first produced chlorine using what we now call hydrochloric acid, and he described it in terms that we recognize pretty easily. It was acidic, suffocating, and "most oppressive to the lungs." He recorded its tendency to bleach things and the immediate death that it brought to insects. Rather that recognizing it as a completely new element, though, Scheele believed that he had found a dephlogisticated version of muriatic acid. A French chemist argued that it was actually an oxide of an unknown element, and that wasn't the end of the arguing. Humphry Davy (whom we mentioned in his ill-fated quest for fluorine), thought it was an oxygen-free compound. This was in complete opposition to the rest of the scientific community, which was convinced that it was a compound involving oxygen. It was only in 1811, well after its first isolation and the debunking of the phlogiston theory, that Davy confirmed it was an element and named it after its color.

乔治·厄恩斯特·斯塔尔介绍说:"燃素理论表明,金属以组成该金属的元素为核心,周围散布有大量的燃素。"18世纪初,化学家使用这种理论解释为什么金属燃烧后发生了实质上的改变。比如说:铁燃烧之后,失去了铁的性质,只留下燃素。该理论不断完善,到了18世纪60年代,人们相信这种物质是"易燃空气",就是我们所熟知的氢。其他元素在该理论中也有提及,比如说氧是"缺乏燃素的空气",而氮是"燃素饱和的空气"。1774年,卡尔·舍勒第一次使用盐酸制备氯气,他描述该物质很容易辨别,显酸性,会使人窒息,并且会对肺部会产生巨大压迫。他还记录了氯气拥有漂白物体的性质,此外,氯气会使昆虫迅速死亡。可惜直到这时舍勒还认为他发现的并不是新元素,而只是一种缺乏燃素的盐酸。一位法国的化学家认为这是一种未知元素的氧化物,但这并不是关于氯讨论的最终结果。汉弗莱·戴维(命途多舛的氟发现者)认为这是一种无氧化合物,这完全与其余科学家的观点相违背,因为大多数科学家确信这是一种含氧化合物。直到1811年,燃素说被推翻,戴维才确信这是一种新元素,并以其颜色命名为氯。

审校:彼得潘 编辑:Carrie Xu 来源:前十网