Newton was a decidedly odd figure—brilliant beyond measure, but solitary, joyless, prickly to the point of paranoia, famously distracted (upon swinging his feet out of bed in the morning he would reportedly sometimes sit for hours, immobilized by the sudden rush of thoughts to his head), and capable of the most riveting strangeness.

牛顿绝对是个怪人--他聪明过人,而又离群索居,沉闷无趣,敏感多疑,注意力很不集中(据说,早晨他把脚伸出被窝以后,有时候突然之间思潮汹涌,会一动不动地坐上几个小时),干得出非常有趣的怪事。

He built his own laboratory, the first at Cambridge, but then engaged in the most bizarre experiments. Once he inserted a bodkin—a long needle of the sort used for sewing leather—into his eye socket and rubbed it around "betwixt my eye and the bone as near to [the] backside of my eye as I could" just to see what would happen. What happened, miraculously, was nothing—at least nothing lasting. On another occasion, he stared at the Sun for as long as he could bear, to determine what effect it would have upon his vision. Again he escaped lasting damage, though he had to spend some days in a darkened room before his eyes forgave him.

他建立了自己的实验室,也是剑桥大学的第一个实验室,但接着就从事异乎寻常的实验。有一次,他把一根大针眼缝针--一种用来缝皮革的长针--插进眼窝,然后在"眼睛和尽可能接近眼睛后部的骨头之间"揉来揉去,目的只是为了看看会有什么事发生。结果,说来也奇怪,什么事儿也没有--至少没有产生持久的后果。另一次,他瞪大眼睛望着太阳,能望多久就望多久,以便发现对他的视力有什么影响。他又一次没有受到严重的伤害,虽然他不得不在暗室里待了几天,等着眼睛恢复过来。

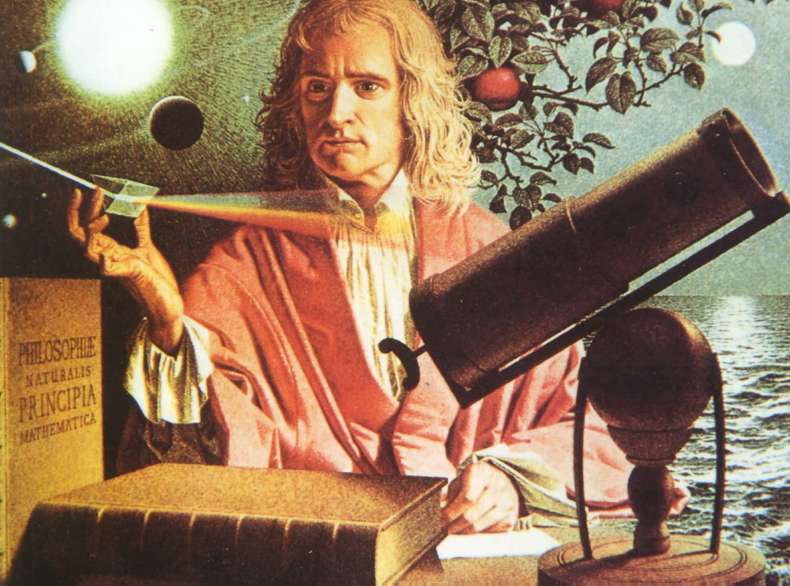

Set atop these odd beliefs and quirky traits, however, was the mind of a supreme genius—though even when working in conventional channels he often showed a tendency to peculiarity. As a student, frustrated by the limitations of conventional mathematics, he invented an entirely new form, the calculus, but then told no one about it for twenty-seven years. In like manner, he did work in optics that transformed our understanding of light and laid the foundation for the science of spectroscopy, and again chose not to share the results for three decades.

与他的非凡天才相比,这些奇异的信念和古怪的特点算不了什么--即使在以常规方法工作的时候,他也往往显得很特别。在学生时代,他觉得普通数学局限性很大,十分失望,便发明了一种崭新的形式--微积分,但有27年时间对谁也没有说起过这件事。他以同样的方式在光学领域工作,改变了我们对光的理解,为光谱学奠定了基础,但还是过了30年才把成果与别人分享。