Capitalizing on Mantell's enfeebled state, Owen set about systematically expunging Mantell's contributions from the record, renaming species that Mantell had named years before and claiming credit for their discovery for himself. Mantell continued to try to do original research but Owen used his influence at the Royal Society to ensure that most of his papers were rejected.

欧文利用曼特尔体弱多病的状态,着手系统地从档案中勾销他的贡献,重新命名曼特尔多年以前已经命名过的物种,把他发现这些物种的功劳占为己有。曼特尔还想搞一些创新的研究工作,但欧文利用自己在皇家学会的影响,确保曼特尔的大部分论文被拒绝采用。

In 1852, unable to bear any more pain or persecution, Mantell took his own life. His deformed spine was removed and sent to the Royal College of Surgeons where—and now here's an irony for you—it was placed in the care of Richard Owen, director of the college's Hunterian Museum.

1852年,曼特尔再也无法忍受疼痛或迫害,结束了自己的生命。他那根变了形的脊椎被取出来送到皇家外科学院——这又是一件很有讽刺意味的事——由该学院的亨特博物馆馆长理查德·欧文保管。

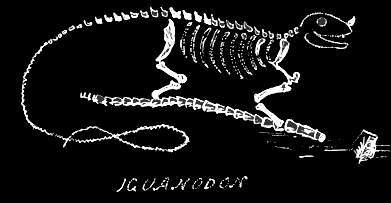

But the insults had not quite finished. Soon after Mantell's death an arrestingly uncharitable obituary appeared in the Literary Gazette. In it Mantell was characterized as a mediocre anatomist whose modest contributions to paleontology were limited by a "want of exact knowledge." The obituary even removed the discovery of the iguanodon from him and credited it instead to Cuvier and Owen, among others. Though the piece carried no byline, the style was Owen's and no one in the world of the natural sciences doubted the authorship.

但是,污辱没有完全结束。曼特尔死后不久,《文学》杂志刊登了一篇极其无情的悼文。在那篇文章里,曼特尔被描述成一名二流的解剖学家,他对古生物学的一点儿贡献“由于缺乏过硬的知识”而受到限制。悼文甚至抹去了他发现禽龙的功劳,把这个功劳归于居维叶和欧文等人。悼文没有署名,但其风格是欧文的,自然科学界谁也不会怀疑作者是谁。