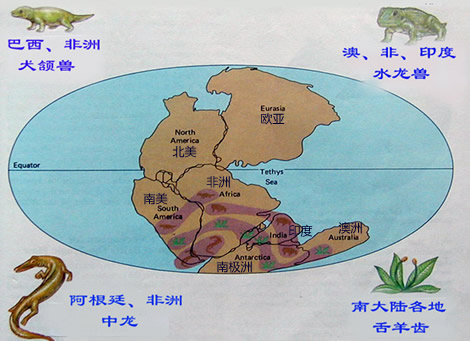

When it was realized that ancient tapirs had existed simultaneously in South America and Southeast Asia a land bridge was drawn there, too. Soon maps of prehistoric seas were almost solid with hypothesized land bridges—from North America to Europe, from Brazil to Africa, from Southeast Asia to Australia, from Australia to Antarctica. These connective tendrils had not only conveniently appeared whenever it was necessary to move a living organism from one landmass to another, but then obligingly vanished without leaving a trace of their former existence. None of this, of course, was supported by so much as a grain of actual evidence—nothing so wrong could be—yet it was geological orthodoxy for the next half century.

Even land bridges couldn't explain some things. One species of trilobite that was well known in Europe was also found to have lived on Newfoundland—but only on one side. No one could persuasively explain how it had managed to cross two thousand miles of hostile ocean but then failed to find its way around the corner of a 200-mile-wide island. Even more awkwardly anomalous was another species of trilobite found in Europe and the Pacific Northwest but nowhere in between, which would have required not so much a land bridge as a flyover. Yet as late as 1964 when the Encyclopaedia Britannica discussed the rival theories, it was Wegener's that was held to be full of "numerous grave theoretical difficulties."