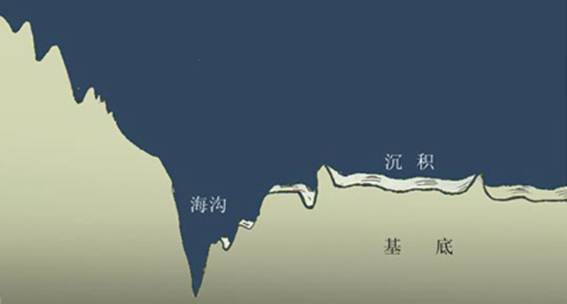

There was one other major problem with Earth theories that no one had resolved, or even come close to resolving. That was the question of where all the sediments went. Every year Earth's rivers carried massive volumes of eroded material—500 million tons of calcium, for instance—to the seas. If you multiplied the rate of deposition by the number of years it had been going on, it produced a disturbing figure: there should be about twelve miles of sediments on the ocean bottoms—or, put another way, the ocean bottoms should by now be well above the ocean tops. Scientists dealt with this paradox in the handiest possible way. They ignored it. But eventually there came a point when they could ignore it no longer.

In the Second World War, a Princeton University mineralogist named Harry Hess was put in charge of an attack transport ship, the USS Cape Johnson. Aboard this vessel was a fancy new depth sounder called a fathometer, which was designed to facilitate inshore maneuvers during beach landings, but Hess realized that it could equally well be used for scientific purposes and never switched it off, even when far out at sea, even in the heat of battle. What he found was entirely unexpected. If the ocean floors were ancient, as everyone assumed, they should be thickly blanketed with sediments, like the mud on the bottom of a river or lake. But Hess's readings showed that the ocean floor offered anything but the gooey smoothness of ancient silts.