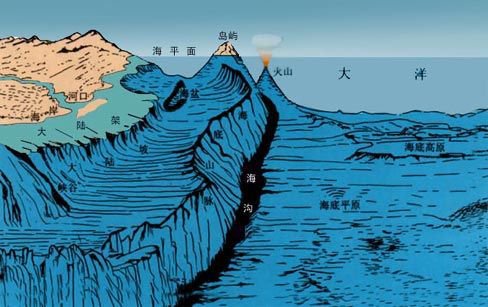

A very little of this had been known for some time. People laying ocean-floor cables in the nineteenth century had realized that there was some kind of mountainous intrusion in the mid-Atlantic from the way the cables ran, but the continuous nature and overall scale of the chain was a stunning surprise. Moreover, it contained physical anomalies that couldn't be explained. Down the middle of the mid-Atlantic ridge was a canyon—a rift—up to a dozen miles wide for its entire 12,000-mile length. This seemed to suggest that the Earth was splitting apart at the seams, like a nut bursting out of its shell. It was an absurd and unnerving notion, but the evidence couldn't be denied.

Then in 1960 core samples showed that the ocean floor was quite young at the mid-Atlantic ridge but grew progressively older as you moved away from it to the east or west. Harry Hess considered the matter and realized that this could mean only one thing: new ocean crust was being formed on either side of the central rift, then being pushed away from it as new crust came along behind. The Atlantic floor was effectively two large conveyor belts, one carrying crust toward North America, the other carrying crust toward Europe. The process became known as seafloor spreading.