Since then further research has shown that there is or may well be a bacterial component in all kinds of other disorders—heart disease, asthma, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, several types of mental disorders, many cancers, even, it has been suggested (in Science no less), obesity. The day may not be far off when we desperately require an effective antibiotic and haven't got one to call on.

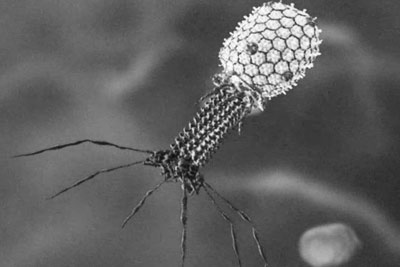

It may come as a slight comfort to know that bacteria can themselves get sick. They are sometimes infected by bacteriophages (or simply phages), a type of virus. A virus is a strange and unlovely entity—"a piece of nucleic acid surrounded by bad news" in the memorable phrase of the Nobel laureate Peter Medawar. Smaller and simpler than bacteria, viruses aren't themselves alive. In isolation they are inert and harmless. But introduce them into a suitable host and they burst into busyness—into life. About five thousand types of virus are known, and between them they afflict us with many hundreds of diseases, ranging from the flu and common cold to those that are most invidious to human well-being: smallpox, rabies, yellow fever, ebola, polio, and the human immunodeficiency virus, the source of AIDS.