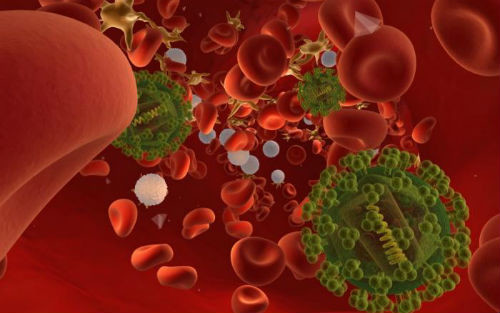

Viruses prosper by hijacking the genetic material of a living cell and using it to produce more virus. They reproduce in a fanatical manner, then burst out in search of more cells to invade. Not being living organisms themselves, they can afford to be very simple. Many, including HIV, have ten genes or fewer, whereas even the simplest bacteria require several thousand. They are also very tiny, much too small to be seen with a conventional microscope. It wasn't until 1943 and the invention of the electron microscope that science got its first look at them. But they can do immense damage. Smallpox in the twentieth century alone killed an estimated 300 million people.

They also have an unnerving capacity to burst upon the world in some new and startling form and then to vanish again as quickly as they came. In 1916, in one such case, people in Europe and America began to come down with a strange sleeping sickness, which became known as encephalitis lethargica. Victims would go to sleep and not wake up. They could be roused without great difficulty to take food or go to the lavatory, and would answer questions sensibly—they knew who and where they were—though their manner was always apathetic.