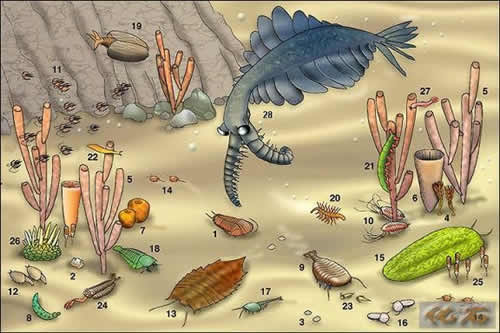

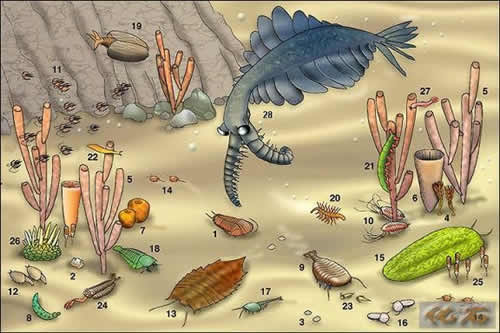

"The Burgess Shale included a range of disparity in anatomical designs never again equaled, and not matched today by all the creatures in the world's oceans," Gould wrote.

“布尔吉斯页岩化石所包含的横剖面的花色范围是独一无一的,今天世界海洋里所有的生物加起来也无法与之匹敌。”古尔德写道。

Unfortunately, according to Gould, Walcott failed to discern the significance of what he had found. "Snatching defeat from the jaws of victory," Gould wrote in another work, Eight Little Piggies, "Walcott then proceeded to misinterpret these magnificent fossils in the deepest possible way." He placed them into modern groups, making them ancestral to today's worms, jellyfish, and other creatures, and thus failed to appreciate their distinctness. "Under such an interpretation," Gould sighed, "life began in primordial simplicity and moved inexorably, predictably onward to more and better."

不幸的是,据古尔德说,沃尔科特没有看到自己的发现的重要意义。“沃尔科特把到手的胜利丢了”,古尔德在另一部作品《八只小猪》中写道,“接着便对这些了不起的化石作出了最错误的解释。”沃尔科特用现代的办法来对它们进行分类,把它们看成为今天的蠕虫、水母和其他生物的祖先,因此没有认识到它们的不同之处。“按照这种解释,”古尔德叹息说,“生命以最简单的形式开始,然后不可阻挡地、可以预测地朝着更多、更好的方向发展。”

Walcott died in 1927 and the Burgess fossils were largely forgotten. For nearly half a century they stayed shut away in drawers in the American Museum of Natural History in Washington, seldom consulted and never questioned. Then in 1973 a graduate student from Cambridge University named Simon Conway Morris paid a visit to the collection. He was astonished by what he found. The fossils were far more varied and magnificent than Walcott had indicated in his writings. In taxonomy the category that describes the basic body plans of all organisms is the phylum, and here, Conway Morris concluded, were drawer after drawer of such anatomical singularities—all amazingly and unaccountably unrecognized by the man who had found them.

沃尔科特于1927年去世,有关布尔吉斯化石的事在很大程度上已经被人遗忘。在将近半个世纪的时间里,那些化石被锁在华盛顿美国自然史博物馆的抽屉里,很少有人去查看,根本无人问津。1973年,剑桥大学一位名叫西蒙·康韦·莫里斯的研究生花钱参观了那批收藏品。他被眼前的化石惊呆了。这些化石要比沃尔科特在他著作中提到的壮观得多,品种也多得多。在分类系统中,描述生物体基本横剖面的类别是门。而在这里,康韦·莫里斯得出结论,是一抽屉又一抽屉如此奇特的横剖面——都是那位发现者不知何故没有认识到的,真是令人不可思议。