What was most surprising, however, was that there were so many body designs that had failed to make the cut, so to speak, and left no descendants. Altogether, according to Gould, at least fifteen and perhaps as many as twenty of the Burgess animals belonged to no recognized phylum. (The number soon grew in some popular accounts to as many as one hundred—far more than the Cambridge scientists ever actually claimed.) "The history of life," wrote Gould, "is a story of massive removal followed by differentiation within a few surviving stocks, not the conventional tale of steadily increasing excellence, complexity, and diversity." Evolutionary success, it appeared, was a lottery.

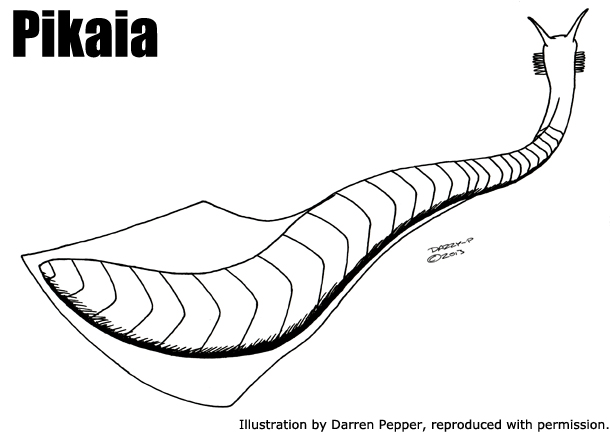

One creature that did manage to slip through, a small wormlike being called Pikaia gracilens, was found to have a primitive spinal column, making it the earliest known ancestor of all later vertebrates, including us. Pikaia were by no means abundant among the Burgess fossils, so goodness knows how close they may have come to extinction. Gould, in a famous quotation, leaves no doubt that he sees our lineal success as a fortunate fluke: "Wind back the tape of life to the early days of the Burgess Shale; let it play again from an identical starting point, and the chance becomes vanishingly small that anything like human intelligence would grace the replay."