This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

Got a minute?

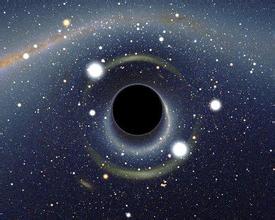

Black holes got their name because light can't escape them, beyond a certain radius, called the event horizon. But in 1974 Stephen Hawking proposed that quantum effects at the event horizon might cause black holes to be...not completely black.

"Hawking said that pairs of particles should be created at the event horizon." Jeff Steinhauer, a physicist at the Israel Institute of Technology. "One particle exits the black hole and travels away, perhaps to Earth, and the other particle falls into the black hole."

Ideally, we could just study those exiting particles...which make up the so-called Hawking radiation. But that signal is too weak. We can't see it against the universe's background radiation. So Steinhauer built a model of a black hole instead. Which traps not photons, but phonons—think of them as sound particles—and it traps of using a gas of rubidium atoms, flowing faster than the speed of sound.

"And that means that phonons, particles of sound, trying to travel against the flow are not able to go forward. They get swept back by the flow. It's like someone trying to swim against a river which is flowing faster than they can swim. And the phonon trying to go against the flow is analogous to a photon trying to escape a black hole."

Steinhauer doesn't actually pipe sound particles into the device. He doesn't need to. He merely created the conditions under which quantum effects predict their appearance. "So the two swimmers can come into existence simultaneously without anybody supplying energy to create them."

He ran the test 4,600 times—the equivalent of six days—and took pictures of the results. And indeed, he saw a correlation between particles emanating into and out of the model black hole…an experimental demonstration of Hawking radiation. The results appear in Nature Physics.

Steinhauer also determined that the partner particles had a quantum connection, called entanglement...which could help theorists investigating the information paradox. "So there's the question of where does information go, if one throws it into a black hole?" This study can't answer that. But, he says, "it helps give hints, to direct physicists towards the new laws of physics, whatever they might be."

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.