This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

Long ago, before Band–Aids, or even medicine of any kind, our ancestors evolved to heal cuts themselves. If you got sliced open, the body blocked it up, to prevent blood loss, water loss, infection. But as we gained that power—we sacrificed something else.

"So we've evolved to heal very quickly, or as quickly as possible, at the expense of regenerating skin the way it used to be." George Cotsarelis, a skin biologist at the University of Pennsylvania who studies that newly healed skin—aka scars. "And the feature of scars is that they don't have hair follicles, sweat glands or fat."

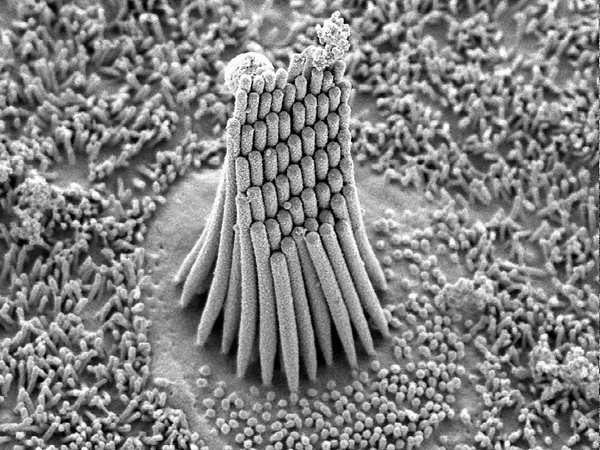

In that observation lies a clue, which Cotsarelis and his team investigated in mice. They found that, when mice were injured, hair follicles sometimes regenerated at the wound site. And where hair cells appeared, fat cells did, too—the fat that sits under normal skin, as a cushion. "The bottom line is that the follicle has these almost magical powers where it's really normalizing the skin architecture." Meaning hair cells are good for reducing scarring.

In their latest work, in the journal Science, they isolated a growth factor called BMP from the hair follicles. It's a signal the follicles send to neighboring cells. They then exposed human scar cells to BMP, in a dish. They found that the growth factor did indeed help to reprogram the scar cells to fat cells, nudging them down a different developmental path.

Cotsarelis says a magic scar-free ointment is probably a ways off. "It's a very complicated process and knowing the timing of when to introduce things, how to introduce them, and the delivery of the compounds is important." But if we figure that out—we might someday be able to coax our skin to heal itself...without leaving visible evidence behind.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.