This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Karen Hopkin.

Got a minute?

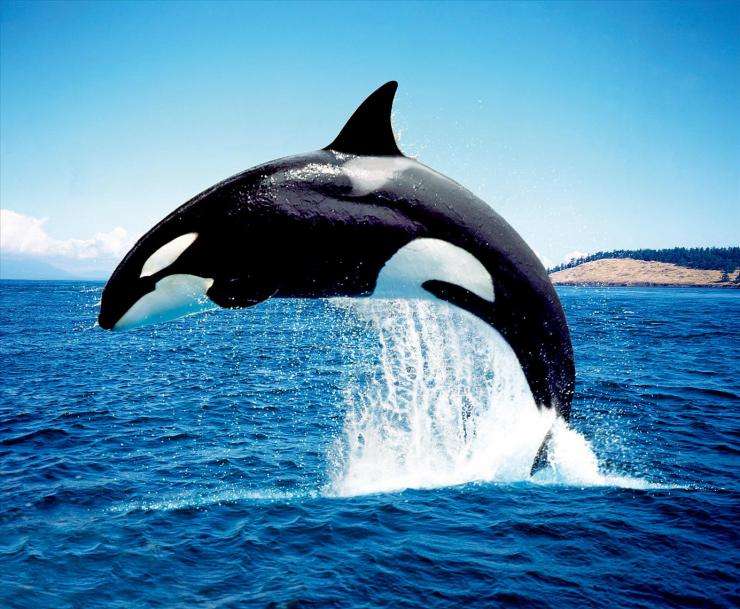

Menopause marks the end of a female's babymaking era. And not just for humans. Female killer whales go through menopause, too. And a new study finds that they might get pushed into menopause by their up-and-coming daughters. Those findings are floated in the journal Current Biology.

Female orcas usually quit popping out calves between the ages of 30 and 40. Yet they can live to be more than 90 years old. One granny orca, who recently dropped from researchers' radar and is (sadly) presumed to have passed, was thought to be 105.

But why would a female whale stick around for so long after she's done adding to the gene pool? One theory is that it pays to keep nanna around so she can help care for the younger members of her family group. Indeed, matriarchal orcas do spend a lot of time nurturing their descendants.

But that doesn't explain why the old gals should stop having babies of their own. To dive deeper into that issue, researchers examined 43 years' worth of demographic data on two populations of killer whales in the Pacific Northwest. The records tracked the ages and genealogical relationships of the resident orcas, including 525 calves.

Turns out that when mothers and daughters breed at the same time, the calves of the elder females—for reasons yet unclear—are almost twice as likely to die by the age of 15 than those of the younger moms. Which the researchers say could account for why the grande dames ultimately give up on reproduction and coast through their golden years doting on the gargantuan grandkids.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science Science. I'm Karen Hopkin.