This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

To learn about the plant life of long ago, scientists dig through layers of the Earth, looking for fossil clues. Like bits of fossilized pollen, or spores.

"And that's where I come in." Timo van Eldijk (EL-dike) is an evolutionary biologist at Utrecht University. He was called into action when his pollen-hunting pals noticed something altogether different, in a sample of sediment more than 200 million years old dug from a thousand feet below the surface of Germany: bits of insect.

"I took a human nose hair, because that's the way you isolate these things. You have a needle tipped with a human nose hair, apparently it has just the right springiness for the isolation."

Whose nose hair? "I don't actually know. There was a joke going around it was one of the professors, but we don't actually know."

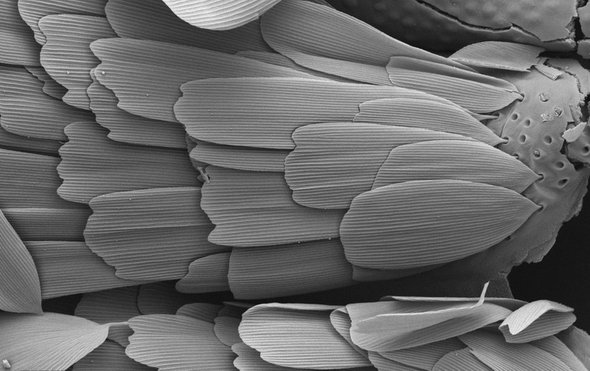

So, using someone's nose hair, van Eldijk picked through the sludgy sediment, and isolated the tiny scales of moth wings—the stuff that looks like dust, if you touch a butterfly or moth.

His team scanned those scales with an electron microscope, and made a crucial discovery: some of the scales were hollow. The fossil record shows that: "First came the proboscis and then came the hollow scales. We can then infer, if we find the hollow scales, there must already have been a proboscis."

So what's the big deal? The finding means that these samples predate existing evidence for the first butterfly tongues by 70 million years. Which in turn implies that an early version of the proboscis, which in modern insects can pry into a flower's nooks and crannies for nectar, appears to have evolved before the appearance of flowers—not as a response. The study is in the journal Science Advances.

The early proboscis might have been used to pluck drops of liquid from the tips of ancient forms of today's pine tree cones. And it's clear that these sucking tongues underwent a lot of remodeling after the emergence of flowers, as flowers and moths co-evolved.

But van Eldijk is hoping insect scales might become more widely used as a tool to investigate the ancient world. "We're hoping that people will start recognizing them in other places. You can even imagine sort of a scenario in which we can reconstruct past ecosystems based on the scales that you find in a core, much similar to the way we do with pollen now."

All scientists have to do is follow their noses—or at least their nose hairs.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.