This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Jason G. Goldman.

Got a minue?

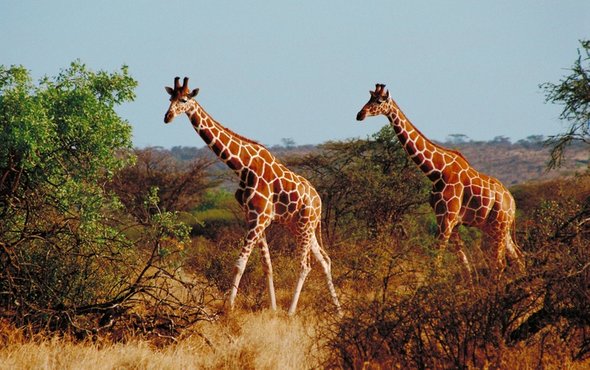

The giraffe is an icon of the African savannah. The lion is the top predator of the ecosystem. Both animals face uncertain futures, and both are subjects of intense, ongoing conservation work. Now a study suggests that saving one might mean bad news for the other.

"When I was out in the field, I heard anecdotes from people that in one of my study sites there were very few juvenile giraffes, because apparently the lions in the area had developed a preference for taking young giraffes."

University of Bristol biologist Zoe Muller. Working in Kenya's Great Rift Valley, she focused her attention on two neighboring sites: a national park with lots of lions, and a privately owned conservancy with no lions.

In the lion-free conservancy, 26 percent of the giraffes were less than one year old. But in the lion-filled park, juvenile giraffes made up only 5 percent of the species' population.

"So I was able to show really that actually in the presence of lions, the number of juveniles is severely reduced, by actually 83 percent. Which was a lot higher than I thought it would be. Quite shocking, actually."

Giraffe populations have declined by some 40 percent in the last 30 years, with fewer than 98,000 individuals left in the wild. In recognition of those figures, they've recently been classified as "vulnerable," that is, likely to become endangered.

The ongoing loss of juveniles could lead to a situation where the population crashes, since population growth and stability both rely on having enough calves survive to sexual maturity—so they, too, can breed and produce offspring of their own.

The study compares only two sites in East Africa. But it highlights the extreme complexity of wildlife management in Africa, where the recovery of one species could potentially come at the cost of another.

"Unfortunately, in East Africa especially, most of the conservation areas these days are fenced and enclosed. And so this is going to become an increasingly more common problem, where we find that predators are being enclosed in specific areas."

Allowing for the conservation of both species in the same areas is thus a tricky proposition. Muller says that one possibility might be to translocate giraffes into and out of lion-free areas, or to translocate lions into and out of places with lots of giraffes. If we do that, we may help ensure the two species' survival. But are they still truly wild?

Thanks for the minute for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Jason G. Goldman.