Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION -- American history in VOA Special English. In eighteen sixty-four, the battle at Cold Harbor in Virginia ended a month of fighting by the Union Army of the Potomac. The campaign had brought the army almost to the edge of Richmond, the Confederate capital. But General Ulysses Grant had paid a terrible price: more than fifty thousand Union dead and wounded. Confederate losses were much lighter -- about twenty thousand. Grant was beginning to learn an important lesson of the war. The methods of defense had improved much more than the methods of attack. This week in our series, Harry Monroe and Kay Gallant continue the story of the American Civil War. By the autumn of eighteen sixty-four, it appeared that the North would defeat the South in the American Civil War. The southern army needed men and supplies. There was little hope of getting enough of either to win. The northern army was stronger and better-equipped. But it, too, had suffered. Much of the death and destruction was the result of new military technology. A new kind of bullet had been invented. It was called the minie ball. It made the gun a much more deadly weapon.

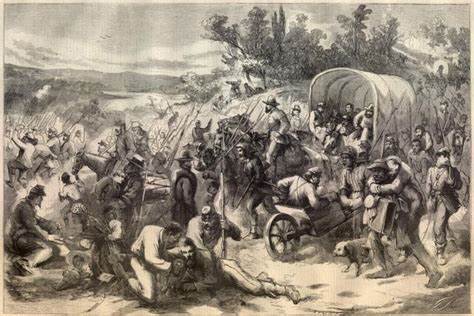

Before the minie ball, few soldiers could hit a target more than thirty meters away. With the new bullet, they could hit targets more than one hundred fifty meters away. Soldiers with such weapons could be put into position behind stone or earth walls. Then it was almost impossible to defeat them. Most American generals, however, seemed unable to accept this. They continued to use the old methods of attack that had worked before the minie ball was invented. Hundreds or thousands of men were put in long lines across the front of the enemy position. A signal was given. The men began to march forward. When they got close, they fired their guns. Then they ran at the enemy and struck with their knives or hands. The idea was to shock the enemy, frighten him, and make him run away. As generals on both sides learned, this method no longer worked. The attackers were shot down before they could get close enough to hurt the defenders. After three and a half years of fighting, hundreds of thousands of Union and Confederate soldiers had been killed or wounded. Still the war continued. In the East, Union armies were slowly pushing forward toward their main target. That was the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. In the West, Union armies were slowly pushing deeper into Confederate territory. The western armies were led by General William Sherman.

Sherman had two goals. One was to capture the city of Atlanta, Georgia. Atlanta was one of the few remaining industrial cities of the Confederacy. The other goal was to destroy the Confederate army led by General Joe Johnston. Sherman's army was stronger than Johnston's army. But the Confederates usually got into better defensive positions. Sherman refused to attack in such situations. It was easier to march around the Confederates and force them to withdraw. This happened again and again. Confederate President Jefferson Davis began to believe that General Johnston was afraid to fight. He replaced him with another general. Within two days, that general attacked the Union Army. The attack began without enough planning. It was based on false information. It was a disaster. In eleven days of fighting, one-third of the Confederate Army in Georgia was destroyed. The remaining force was too weak to defend Atlanta. The city fell. After capturing Atlanta, General Sherman fought a series of small battles with a Confederate force across northern Georgia. Then he decided to march to Savannah, a city on the Atlantic coast. Before leaving, his men set fire to the city. Almost all of Atlanta was destroyed.

Sherman's army would continue to do this all the way to Savannah, Georgia, three hundred fifty kilometers away. It cut a path of destruction more than one hundred kilometers wide. This campaign would be known as Sherman's March to the Sea. Sherman said he wanted to make the people of Georgia suffer. He said he wanted to show the people of the Confederacy that their government could not protect them. Union soldiers stopped at every farm and village. They took food and clothing. They took horses, cows, and other farm animals. What they could not take, or did not want, they destroyed. They set fire to houses and farm buildings. They burned crops. They destroyed stores and factories. They burned bridges and pulled up railroad tracks. Day by day, the Union army of General William Sherman cut and burned its way across Georgia. The army faced little opposition. Small groups of Confederate horse soldiers struck at the edges of the army. But they did little damage. On December twenty-second, eighteen sixty-four, Sherman reached Savannah. He sent a message to President Abraham Lincoln in Washington. He said: "I beg to present you, as a Christmas holiday gift, the city of Savannah."

Sherman's campaign had cut a great wound in the heart of the Confederacy. All that remained were the states of South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. His march to the sea had a great, destructive effect on the spirit of the South. Sherman's army rested in Savannah for a month. Then, on February first, eighteen sixty-five, it began to move north. The goal was to join General Ulysses Grant outside the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. As Sherman's army moved across South Carolina, it destroyed almost everything in sight. The soldiers remembered that South Carolina had been the first state to rebel and leave the Union. They remembered that South Carolina had fired the first shots of the war. This time -- against orders -- they destroyed the land they left behind. Confederate forces could not stop them. The same thing happened in the Shenandoah River Valley northwest of Richmond. In the early years of the war, Confederate forces had moved through the valley to strike northern territory. They had invaded Maryland and Pennsylvania, and had threatened Washington, from there. General Grant decided that the Confederates had used the Shenandoah Valley long enough.

He sent some of his men into the valley. He ordered them to destroy everything that might be of use to the enemy. "Eat up Virginia," he said, "clear and clean as far as you can go." Farms were burned. Crops were destroyed. Farm animals were taken away or killed. Nothing was left that could feed a man or animal. Nothing but blackened earth. Then General Grant sent General Philip Sheridan into the Shenandoah Valley. Sheridan's army battled its way through the valley in the autumn of eighteen sixty-four. It gained victory after victory against a smaller, weaker Confederate force. By the end of the year, Union troops had complete control of the valley. The only Confederate power that remained was the army of General Robert E. Lee. With the Shenandoah Valley closed to the Confederates, food supplies fell very low. There was almost nothing to feed the soldiers in Lee's army. Wagons would go out each day in search of food. They returned almost empty. More and more Confederate soldiers were running away. Some returned to their homes. Others surrendered to Union forces.

Confederate leaders no longer could find soldiers to take the places of those who left. Men would not answer the army's call. There was, however, a huge labor force in the South that the army had not called: slaves. Slaves had been used to do non-military work for the army. They had built roads and bridges. They had driven wagons. But they had not served as soldiers. In the North, thousands of free Negroes served in the Union army. But they received less pay than white soldiers. Confederate lawmakers finally began to discuss the idea of using slaves as soldiers. A bill was proposed that would free any slave who joined the army to fight. Many southern leaders opposed the bill, even if it would save the Confederacy. Said one: "Do not arm the slaves. The day you make them soldiers is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves make good soldiers, our whole idea of slavery is wrong." General Robert E. Lee did not agree. He believed slaves could be made into good soldiers if they believed they had an interest in Confederate victory. He proposed giving immediate freedom to any slave who joined the army. The Confederate Congress passed a bill in March of eighteen sixty-five to accept Negroes as soldiers. The bill did not promise to free them. By then, however, it was too late. An army of freed slaves could not be trained in time to save the Confederacy.